Internet Access Disruption in Turkey - July 2016

Emile Aben, Leonid Evdokimov, Maria Xynou

2016-07-19

With the attempted coup in Turkey, reports went out about social media being throttled and/or blocked. We analysed data about this that we collected with RIPE Atlas and the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI).

On 15 July, a coup was attempted in Turkey. We heard about social media being throttled and/or blocked, but much was unclear about what was actually going on. Here we present measurement data from various platforms that shared their data publicly.

RIPE Atlas

Looking at the RIPE Atlas data, we didn’t find anything consistent and/or structural in the latency data from 15 July that pointed towards changes in connectivity for our RIPE Atlas measurement points (called “probes”). That said, an anomaly detector for RIPE Atlas traceroutes is actively being worked on, which we can potentially use to look at events like this in the near future.

When we looked into the data for SSL certificate fetches from probes, though, we did find something interesting. For a general SSL certificate fetch measurement from Turkish RIPE Atlas probes that ran continuously on 15 July and the days before and after, no anomalies were detected for RIPE Atlas probes in Turkey. However, when we looked at specific measurements that were started by our users to measure SSL certificate fetches from Turkey for Twitter and Facebook, you can see anomalies.

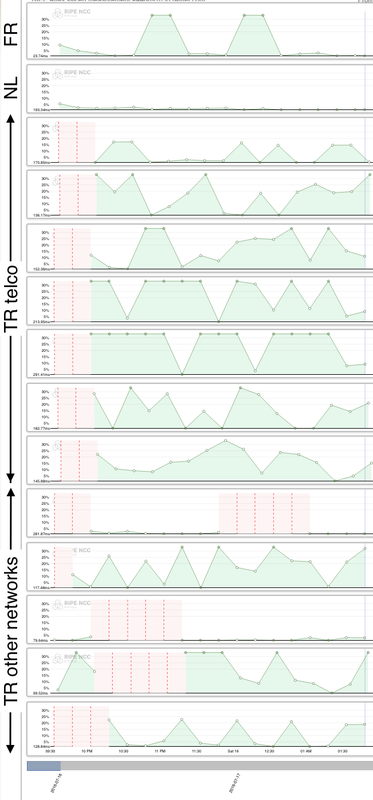

The Twitter measurement started around 21:30 UTC and LatencyMON results for it can be seen in Figure 1 below. What can be seen here is that, for multiple networks in Turkey, Twitter SSL fetches failed when this measurement started at 21:30 UTC. This measurement does not distinguish between blocking and severe throttling; the SSL measurement times out after five seconds, which could be the result of either. Networks where the fetch continued to work are not shown in this picture.

For the incumbent telco, the fetches started working again at around 22:00 UTC (which is midnight in Turkey), but for other networks, the time periods when the fetches failed are not aligned. If our measurements indeed captured Twitter censoring in Turkey, this suggests that networks were implementing the blocking independent from each other. In other words, we see no evidence that there is a mechanism in place that allows the Turkish government to automatically and widely block specific services. And while the incumbent telco owns a large part of the market, both in facilitating Internet access to end users as well as providing transit services to other ISPs, if an order goes out to block certain specific services, it seems it’s up to each individual network to actually make this happen.

A Facebook SSL measurement was started about an hour later, at which point the main telco didn’t block anymore, but the patterns for the other networks were similar.

Figure 1: Twitter SSL certificate fetches from RIPE Atlas probes in Turkey on July 15. Red indicates a failed SSL certificate fetch.

The SSL measurement towards Twitter, Facebook and YouTube also contains hostname lookups for twitter.com, facebook.com and youtube.com. Normally these DNS lookups point to address space that used by the corresponding company, but for all three domains we found the lookups being directed towards address space used by the incumbent telco. We found 17 cases of this DNS hijacking between 22:13 UTC and 23:17 UTC, from two different probes in two different networks, where both networks used the incumbent telco as their upstream network.

For networks where we do not have multiple probes in each network, it’s worth noting that we cannot isolate any probe-specific effects that might exist in the measurements.

OONI

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is a free software project under the Tor Project that aims to detect Internet censorship, traffic manipulation and signs of surveillance around the world through the collection and processing of network measurements.

OONI’s HTTP request test was run in Turkey at 4:30 UTC on 15th July to test a set of URLs - including twitter.com, facebook.com and youtube.com - for censorship. This test is designed to examine whether URLs are blocked based on a comparison of HTTP requests over Tor vs. the user’s network. OONI’s measurement data indicates that twitter.com, facebook.com and youtube.com did not appear to be blocked on the morning of 15th July leading up to the attempted military coup. However, it’s worth noting that these measurements were only conducted from one network vantage point within Turkey, and that OONI tests were not run during or following the attempted coup.

Tor use

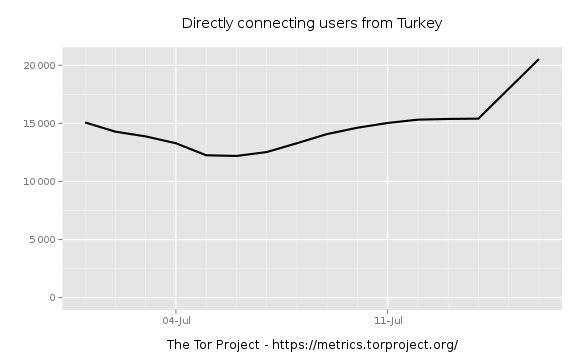

With specific social networks being blocked, or at risk of being blocked, it is to be expected that users wanting to access these networks will try to circumvent blocking. One way of doing that is to use Tor. Figure 2 is taken from the telemetry that Tor puts online about the number of users per country. It shows that the day after 15 July, the number of Tor users in Turkey increased significantly, from 15,000 to 20,000.

Figure 2: Tor users connecting from Turkey. Data taken from https://metrics.torproject.org/

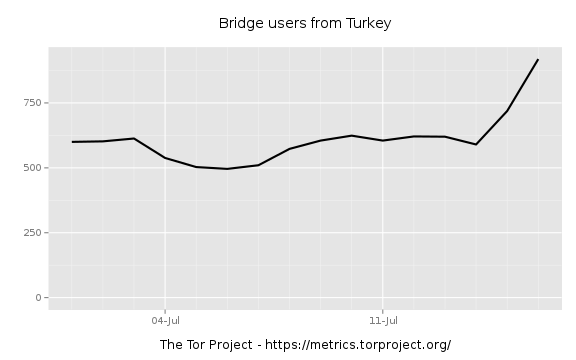

Similarly, an increased use of Tor bridges, designed to circumvent the blocking of access to the Tor network, occurred during the same period, as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Usage of Tor bridges in Turkey from 1-16 July 2016. Data taken from https://metrics.torproject.org

Traffic volumes

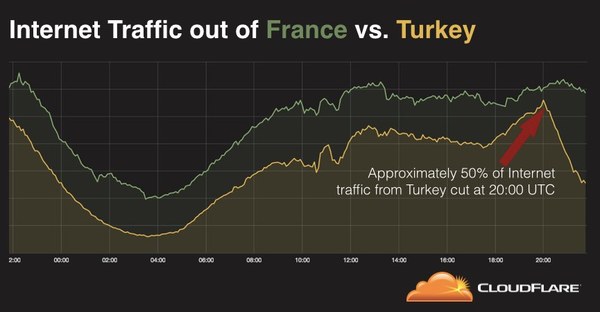

Except for IXPs sharing it publicly, we don’t have much public data about traffic volume on the Internet. For this information we are at the mercy of people willing to share it. Luckily, Cloudflare shared their traffic levels for 15 July, which showed a significant drop in traffic volume from Turkey, with the traffic volume from France as a reference (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Cloudflare traffic levels from Turkey and France on 15 July. Data from a tweet by @eastdakota.

Conclusion

In recent years, Turkey has had a history of selectively blocking Internet access. With operators sharing information, and using measurements from RIPE Atlas and OONI, monitoring the Internet access situation has become more transparent and open and we can better understand and share what’s actually going on, to the extent that we don’t cause harm for any of our users or the network operators involved. With OONI, users are specifically and explicitly measuring censorship, which is outside the scope of what RIPE Atlas can do; as such, we feel our network measurement infrastructures are complementary.

If users want to help detect censorship, they can help - after carefully assessing the risks involved - by installing OONI Probe.

The situation in Turkey is a bit special, because diametrically opposed to the practice of Internet blocking is the United Nations Human Rights Council’s resolution on the promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet, which condemns countries that intentionally disrupt citizens’ Internet access. Turkey was one of the six countries that took the initiative on the resolution.

This post was originally published by RIPE Atlas here.