South Sudan: Measuring Internet Censorship in the World's Youngest Nation

Maria Xynou (OONI), Kenyi Yasin Abdallah Kenyi (TAHURID), Leonid Evdokimov (OONI), Stanley Nyombe Gore (TAHURID)

2018-08-01

Image by Mandavi

Established in July 2011, South Sudan is the youngest country in the

world. But the transition to independence from Sudan has been far from

smooth, as the country experiences an ongoing civil war. Even though

internet penetration levels remain quite low, two media websites and two independent blogs were reportedly blocked

last year.

This report is a joint research effort by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and South

Sudan’s The Advocates for Human Rights and Democracy (TAHURID). We examine internet

censorship in South Sudan through the collection and analysis of

network measurements.

Our findings corroborate

reports

on the blocking of media outlets Sudan Tribune

and Radio Tamazuj,

and independent blogs

Nyamilepedia

and Paanluel Wel,

suggesting that these sites have been blocked for a year. MTN appears to

block TCP/IP connections to these sites, while IPTEC appears to block

access by means of DNS tampering. Measurements collected in 2017

highlight the presence of the Mikrotik HTTP transparent proxy.

Background

South Sudan has been plagued by civil wars over the last

century.

The first Sudanese civil war

was a conflict from 1955 to 1972 between the northern part of Sudan and

the southern Sudan region that demanded more autonomy. Following the

first civil war, the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region was temporarily

formed, but a second civil war

erupted in 1983 and lasted until the end of 2004. After the second civil

war, the Autonomous Government of Southern Sudan was created. South

Sudan became an independent state on 9th July 2011,

following a referendum.

The country though remains in turmoil. Two years after independence, a

civil war erupted

within South Sudan between the government and opposition forces. In

2015, an

agreement

to end South Sudan’s civil war was threatened by ceasefire violations

and the war restarted

by July 2016. South Sudan’s ongoing civil war has resulted in the

displacement of millions (who have

seeked refuge in neighbouring Uganda, Sudan, and Kenya) and in tens of thousands of deaths

(though aid workers reported in 2016

that the true figure might be as high as 300,000 deaths, which is

comparable to the number killed in Syria during five years of war).

Recently, the Security Council of the United Nations renewed sanctions

(previously imposed in 2015) on South Sudan for 45 days, setting a

deadline

for the civil war to end by 30th June 2018. Even though South Sudan’s

main belligerents came to a peace agreement in late June 2018, experts

worry

that it fails to solve issues that have been at the heart of the civil

war.

Amid conflict and political turbulence, South Sudan has one of the

least developed

telecommunications and internet systems in the world. Fifteen Internet

Service Providers (ISPs) operate in South Sudan, but the lack of

fibre-optic cables and the limited availability of public power hinder

connectivity. MTN enjoys the greatest share

within the mobile phone market, followed by Vivacell and Zain. Earlier

this year however, Vivacell’s license was

suspended

for not paying USD 60 million

in fees.

Internet penetration levels have

increased

since independence in 2011, but remain quite low. According to the

National Communication Authority, around

20.5%

of South Sudan’s population is estimated to have access to the internet,

mostly concentrated in Juba and largely based on mobile internet

subscriptions.

South Sudan’s Transitional Constitution of 2011

guarantees freedom of expression and press freedom under Article 24,

with possible exceptions for public order, safety, or morality. The

Article also calls on media to abide by professional ethics. Article 32

of the Transitional Constitution guarantees the right to access official

information, with exemptions for public security and personal privacy.

The regime though regularly violates media freedom

protections in practice, and government officials have engaged in

rhetoric that contributes to a hostile environment for the press.

Two media websites and two independent blogs were reportedly blocked

in South Sudan in July 2017. The censored sites include Paris-backed

Sudan Tribune and Dutch-backed Radio Tamazuj, as well as the

Nyamilepedia and Paanluel Wel blogs of the Nuer and Dinka tribes,

South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups.

Measuring internet censorship

In an attempt to verify

reports

on the blocking of websites and to examine South Sudan’s internet

landscape more broadly, we ran OONI Probe network measurement

tests in South Sudan.

OONI Probe consists of a number of software tests that scan TCP, DNS, HTTP and TLS

connections for signs of network tampering. Some tests request data over

an unencrypted connection and compare against a known good value. Others

check for HTTP transparent proxies, DNS spoofing, and network speed and

performance.

To measure the blocking of websites, we started off by carrying out some

research

to identify South Sudanese URLs to test. We subsequently

added these URLs

to the Citizen Lab’s test list repository on GitHub, since OONI Probe is

designed to measure the blocking of URLs included in these test lists.

Over the last few months, we primarily ran OONI Probe’s Web Connectivity test (among

other OONI Probe tests) in two networks: MTN South Sudan (AS37594) and

IPTEC Limited (AS36892).

As part of our testing, we measured the blocking of URLs included in the

global

(including internationally relevant sites) and South Sudanese

(including sites relevant to South Sudan) test lists. Once we collected

OONI Probe network measurements from South Sudan, we analyzed them with

the aim of identifying network anomalies that could serve as signs of

internet censorship.

Blocked websites

Last year, media outlets Sudan Tribune

and Radio Tamazuj, and independent blogs

Nyamilepedia and Paanluel Wel, were reportedly blocked

in July 2017. Our recent testing not only corroborates these reports,

but also suggests that these sites remain blocked one year later.

The following table links to network measurements pertaining to the

recent testing of each of these sites across two ISPs.

Our findings suggest that MTN (AS37594) blocks TCP/IP connections to

these sites, while IPTEC (AS36892) blocks access by means of DNS

tampering. It’s worth noting that both MTN and IPTEC block access to

both http://sudantribune.com and http://www.sudantribune.com.

South Sudanese authorities blocked these sites for publishing

“subversive content” and

stated

that the bans would not be lifted until those institutions “behaved

well”. Sudan Tribune and Radio Tamazuj are foreign-based media outlets

accused

of hostile reporting against the government.

Paanluel Wel is a leading blog for the

Dinka tribe, known for spearheading tribal political interests for the

Dinka people and inciting hatred and violence against the Nuer people

and other tribes. Nyamilepedia, on the other

hand, is a leading blog for the Nuer tribe, known for promoting Nuer

political interests and spearheading hatred against the Dinka and other

Nuer who left the rebellion to join the Dinka-led government.

TAHURID reports that

Almshaheer and South Africa’s Centre for Conflict Resolution are inaccessible on

IPTEC, but accessible on MTN (the accessibility of which is also

confirmed by OONI data testing

almshaheer.com

and

ccr.org.za).

Many other URLs presented network anomalies (such as HTTP failures) as

part of our testing, but such anomalies were most likely caused due to

poor network performance and transient network failures. This suggests

that South Sudanese internet users may encounter challenges in accessing

sites in various points in time, even if they’re not intentionally being

blocked.

It’s worth highlighting, however, that many of the URLs that we tested

(including internationally popular and local sites) were found to be

accessible in South

Sudan during this study. These include sites related to conflict

resolution and peacekeeping, such as the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS)

site.

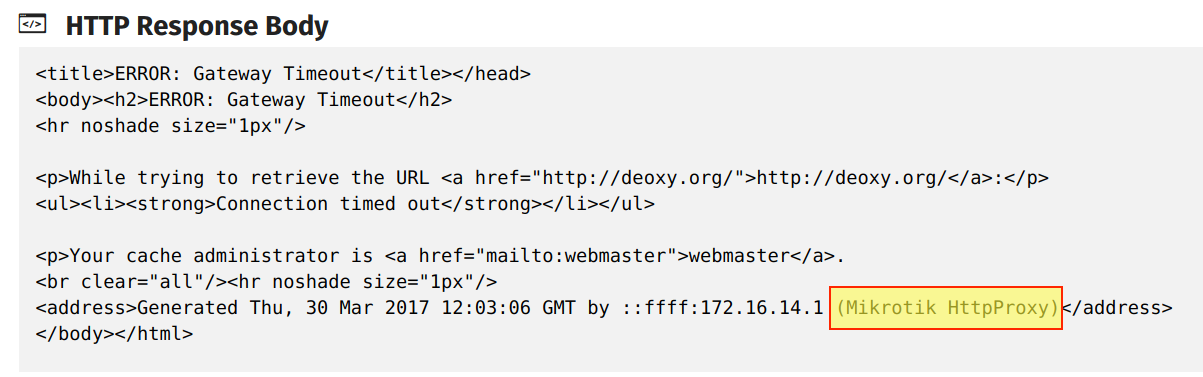

HTTP proxy

Measurements previously collected in 2017 highlight the

presence of an HTTP transparent proxy (Mikrotik).

This proxy is revealed in the HTTP response body in OONI Probe

measurements (linked below) pertaining to the testing of the following

sites:

These measurements clearly show that the Mikrotik HTTP transparent proxy

was present last year in the network path to the above sites through

South Sudan’s 4G Telecom (AS327786) network. It remains unclear though

if this proxy is still in use, since measurements haven’t been collected

from this network in recent months.

It’s worth noting that this equipment may potentially be used for

implementing internet censorship and/or for caching (the Mikrotik HTTP

proxy has this feature) to improve connectivity. Given though that most

of these sites were

accessible (and the

ones that weren’t presented different errors, sometimes triggered as

part of anti-DDoS protection), it may be the case that this proxy was

primarily deployed for improving connectivity and network performance.

Conclusion

South Sudan is a young nation in politically turbulent times. Within the

context of conflict, local experts

discuss

the challenges of drawing a line between freedom of expression and

hate speech,

which spurs violence.

Internet censorship does not appear to be pervasive, but limited to

sites that authorities

deem

to publish “subversive content” and incite violence. This is evident

through the blocking of

Nyamilepedia

and Paanluel Wel,

the leading blogs of the Nuer and Dinka tribes who are known to incite

violence. OONI data also

corroborates the blocking of media outlets Sudan Tribune

and Radio Tamazuj,

both of which are hosted outside of South Sudan. Local journalists and

media organizations though face different (non-digital) forms of

censorship.

Juba Monitor, for example, is an

independent South Sudanese newspaper critical of the government. Their

website was found to be

accessible,

but their editor was

jailed

in 2016 as a result of his reporting and the newspaper has been

ordered to cease its publishing

over reports that the government considered “against the system”.

Security personnel has been

deployed

at the printing press, forcing journalists to remove or edit articles

critical of the government and its officials prior to publication.

Self-censorship might be one of the most effective forms of censorship

in South Sudan, as suggested by the reported

intimidation

and killing of journalists.

Local experts

argue

that the media in South Sudan operate in a state of fear. Earlier this

year, even UN-backed Radio Miraya was

suspended

on the grounds of not having acquired a broadcasting license.

Nonetheless, the fact that South Sudan has already started implementing

internet censorship raises questions as to whether its internet

censorship apparatus will expand as internet penetration levels increase

and political events unfold. Further research and testing is therefore

required to better understand the country’s internet landscape and

monitor any new censorship events.

This study offers some initial observations based on network measurements. Since we used

free and open source software,

open methodologies, and open data, our research can

potentially be reproduced and expanded upon.