OONI Software Development Guidelines

Arturo Filastò (OONI)

2019-02-23 01:00 UTC

The goal of this document is to explain and explicit some of the best practices relevant to software development that we follow at the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI).

By following these development guidelines we aim to produce higher quality code, which contains less defects and allows us to iterate more quickly delivering greater value to our end users is a shorter amount of time!

Version control

Also known as: “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Git!”

Reasons to love git and version control include:

- History. You have a complete long-term change history of every file in your source tree.

- Branching & Merging. This means that team members can work on the same codebase at the same time, without losing sanity (well for the most part, read on to learn what you can do to prevent insanity).

- Transparency. We are an open source project and as such, it’s important that our community can see what we are up to and that they can trace back to when and why some changes were done on our software.

Each of the OONI products may follow slightly different git patterns and workflows, but the guidelines and rules documented here will apply for the most part to all of them.

Branches

Branches are one of the most powerful features of git.

The most important branch in git is most often called master or main, and is the default branch. In the remainder of this guide we are going to use main as a name for the default branch, but long-running repositories may still be using master as a name for the default branch. The code that is merged into the main branch should pass all the tests (see: Testing section) and it should be possible to build a working version of the product from this branch.

Every time you start working on a new feature, fixing a bug or preparing a new release, create a new branch. Seriously, do it, they are free! This is essential for enabling code review.

When creating a new feature, bugfix or release branch, always do so from the tip of main.

It’s good to include an indication of the github issue the branch is implementing (and create an issue if it does not exist), example of good branch names:

- bugfix/113 (113 is the issue number of a bug this branch is fixing)

- release/2.0.2 (2.0.2 is the version for this release branch)

- feature/reupload (this is about a feature that has to do with reuploading)

Examples of not so great branch names are:

- bugfix (it does not mention which bug it’s fixing)

- andrea (this is a great name for a human, but not so much for a branch)

Once you have finished working on the feature or bugfix and are ready to have it be merged into main, open a pull request, check that all the tests are passing and request that somebody does a review of it (see Code Review section).

Once you branch has been merged into main, feel free to delete it.

Avoiding conflicts

Out of sync branches and conflicts are one of the most frustrating occurrences in git. They cannot be entirely avoided, but here are some things you can do to minimise them:

- Do not force push to the main branch, unless you understand the consequences of it (it’s probably a bad idea anyways)

- Ensure that the branch you are working on is always in sync with main

- If the branch you are working on is not in sync with main, make a copy of your working tree and do the merge (or rebase) inside of another branch (you can create as many copies of the same branch via

git branch branch-copy) - Coordinate with your team members if you are planning to do an important refactoring or changes that will affect many files and ensure that they don’t have uncommitted code

- Don’t keep pull requests open for too much time and merge branches into main often.

Testing

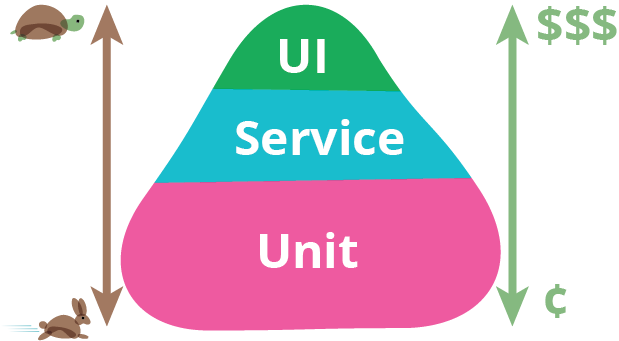

The TestPyramid, popularized by Martini Fowler, says that to have a balanced portfolio of tests you should have much more low level unit tests, than end to end integration or UI tests.

But what are unit tests, end-to-end tests, and integration tests?

Quoting from Code Complete Chapter 22 “Developer Testing”:

Testing is the most popular quality-improvement activity—a practice supported by a wealth of industrial and academic research and by commercial experience. Software is tested in numerous ways, some of which are typically performed by developers and some of which are more commonly performed by specialized test personnel:

- Unit testing is the execution of a complete class, routine, or small program that has been written by a single programmer or team of programmers, which is tested in isolation from the more complete system.

- Component testing is the execution of a class, package, small program, or other program element that involves the work of multiple programmers or programming teams, which is tested in isolation from the more complete system.

- Integration testing is the combined execution of two or more classes, packages, components, or subsystems that have been created by multiple programmers or programming teams. This kind of testing typically starts as soon as there are two classes to test and continues until the entire system is complete.

- Regression testing is the repetition of previously executed test cases for the purpose of finding defects in software that previously passed the same set of tests.

- System testing is the execution of the software in its final configuration, including integration with other software and hardware systems. It tests for security, performance, resource loss, timing problems, and other issues that can’t be tested at lower levels of integration.

From the perspective of OONI, we generally focus our testing efforts on Unit testing & Integration testing.

As part of Integration testing, we will sometimes speak about end-to-end testing or UI testing, when we are speaking about various software services running and speaking to each other or testing by means of controlling the application UI respectively. These subtypes still fit under the broad integration testing label.

One thing to keep in mind, as part of developing a solid testing strategy for a new software component, is that it’s normal and natural that in the beginning it will take significantly more time to set up scaffolding for testing. This initial effort, though, will pay off in the long run as it will then be easier to implement new tests in the future and it will be easier to debug and identify bugs quicker!

Every software project is different and there is no “one-size fits all” approach to testing, but at a bare minimum every OONI product which is in production should be doing at least some unit or integration tests, and ideally both.

To go back to the testing pyramid above, the reason to have more unit tests than integration tests is that generally integration tests are more prone to breaking when changes are made to the software. Moreover, they generally take more time to run, making it less likely for developers to run them as often (for example, automatically as you save your code). They are also more likely to exhibit non deterministic failure, reducing the confidence in testing.

At OONI we have all our unit & integration tests run as part of a commit hook on the continuous integration (CI) system we use for each repository (typically GitHub Actions, Travis CI, or Circle CI). This allows us to ensure that, at the very least, the tests are passing before anything is merged into main.

A branch cannot be merged into main until the failing CI checks are resolved.

There are different tools for implementing unit & integration tests for a variety of different languages. Find a tool which works for the language (or framework) you are developing for and familiarise yourself with them.

A great article to read on Integration Testing is the one by Martin Fowler: https://martinfowler.com/bliki/IntegrationTest.html

Code Review

Code review is about having somebody else review your work, before this makes its way into a final release.

Before explaining our approach to code review, let’s see why this is important.

Why do we do code reviews?

Quoting from section “Chapter 21: Collaborative Construction” of Code Complete:

The primary purpose of collaborative construction is to improve software quality. As noted in Chapter 20, “The Software-Quality Landscape,” software testing has limited effectiveness when used alone—the average defect-detection rate is only about 30 percent for unit testing, 35 percent for integration testing, and 35 percent for low-volume beta testing. In contrast, the average effectivenesses of design and code inspections are 55 and 60 percent (Jones 1996). The secondary benefit of collaborative construction is that it decreases development time, which in turn lowers development costs. Early reports on pair programming suggest that it can achieve a code-quality level similar to formal inspections (Shull et al 2002). The cost of full-up pair programming is probably higher than the cost of solo development—on the order of 10–25 percent higher—but the reduction in development time appears to be on the order of 45 percent, which in some cases may be a decisive advantage over solo development (Boehm and Turner 2004), although not over inspections which have produced similar results.

[…]

Various studies have shown that in addition to being more effective at catching errors than testing, collaborative practices find different kinds of errors than testing does (Myers 1978; Basili, Selby, and Hutchens 1986). As Karl Wiegers points out, “A human reviewer can spot unclear error messages, inadequate comments, hard-coded variable values, and repeated code patterns that should be consolidated. Testing won’t” (Wiegers 2002). A secondary effect is that when people know their work will be reviewed, they scrutinize it more carefully. Thus, even when testing is done effectively, reviews or other kinds of collaboration are needed as part of a comprehensive quality program.

Another benefit that comes from doing code review is that it allows us to transfer knowledge to other members of the team. By always ensuring that somebody else reviews your code (and possibly ask questions on bits that are unclear to them), we are also teaching other members of our team something new. This is great!

How to code review

Ideally, every single line of code that we write and which is included in an end product would be reviewed by at least another OONI team member.

This should in general be what we aim for, but we should also acknowledge that this is not always possible, due to other real world constraints.

Whether you are fixing a bug, implementing a new feature, or working towards a new release, you should always do so in a github pull request by means of a feature/bug/release branch (regardless of whether you plan to have someone review your code or not).

This makes it possible for other OONI team members, even retroactively, to take a look at the work you did.

Ideally, especially if working on a complex feature or resolving a critical bug, you should have somebody other than yourself sign off on the pull request before merging it.

To make the work of the reviewer easier, be sure to:

- List what sort of feedback you are looking for in the review (ex. are there some bits of the PR which are most tricky?)

- Mention what is the best way to review the pull request (going on a commit by commit basis, look at the full diff, inspect the source tree, etc.)

- Ensure the commit history includes meaningful git commit messages (see git best practices section)

Once you have written these in the pull request comment, be sure to request a review from one or more people. Request a review from as many people you think is necessary and merge when at least one person has completed it.

By asking people to review your code, you are being a champion!

By reviewing the code of someone else, you are being a hero!

In-depth reading

- The Pragmatic Programmer: Good book to read cover to cover (or just skim through) and is quite light.

- Code complete: This book is a great book to have on your shelf and refer to from time to time by reading through the relevant section.

- Clean code: Similar type of book as Code Complete.

- The Mythical Man Month: Not really focussed on software development, it’s old, but it’s a classic and has some anecdotes that are still relevant in this day and age.