The State of Internet Censorship in Malaysia

Maria Xynou (OONI), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Khairil Yusof (Sinar Project), Tan Sze Ming (Sinar Project)

2016-12-20

Block page in Malaysia

A research study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and

Sinar Project.

Table of contents

Country: Malaysia

Probed ISPs: TM Net (AS4788), TM-VADS DC Hosting (AS17971)

Censorship method: DNS injection (block pages)

OONI tests: Web Connectivity, Vanilla Tor, HTTP invalid request

line, HTTP header field manipulation, Meek Fronted Requests test

Key Findings

New OONI data

published in this report reveals that 39 different websites were

blocked in Malaysia by ISPs through the DNS injection of block

pages. These sites include:

News outlets, blogs and medium.com for covering the 1MDB scandal.

A site that expresses heavy

criticism towards Islam.

Popular torrenting sites (such as thepiratebay.org).

A popular online dating site.

Pornographic sites.

Gambling sites.

While the blocking of some sites (such as pornography and online

gambling) can be legally justified under Malaysia’s laws and

regulations, the blocking of sites covering the 1MDB scandal

illustrates that such censorship was politically motivated.

On a positive note, some previously blocked sites

(Bersih rally websites) were found to be

accessible

when tested between September to November 2016. No signs of censorship

were detected when examining the accessibility of social media,

censorship circumvention tools and LGBTI websites in the country during

the testing period.

View the data collected as part of this study:

Introduction

Malaysia is a Federal Constitutional Elective country with Westminster

Parliamentary System. Malaysia has a population of around 30.9 million,

with broadband penetration 72.2% for households and 91.7% for individual

users, while the figures surpass the population figures for access to

the internet on mobile phones. More than 80 percent of Internet users

live in urban areas, and penetration remains low in less populated

states in East Malaysia.

Malaysia’s constitution provides citizens with “the right to freedom of

speech and expression,” and MSC Malaysia has guaranteed in the Bill of

Guarantees No.71 that it will ensure there is no censorship on the

internet. However, as of November 2015, 37 incidents

have occurred involving the investigation, arrest, charge and/or

punishment of individuals under the Communication and Multimedia Act

(CMA) documented by SUARAM. Various websites have also been

blocked

over the last year, especially following the 1MDB scandal and

subsequent retaliation against sites covering the

scandal.

In light of recent censorship events in

Malaysia, the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), in collaboration with Sinar Project, conducted a study to examine

whether internet censorship events were persisting in the country and,

if so, to collect data that can serve as evidence of them. This study

was carried out through the collection of network measurements from two

local vantage points in Malaysia, based on OONI software tests designed to examine

whether a set of websites were blocked, and whether systems that could

be responsible for internet censorship and surveillance were present in

the tested networks (AS4788 and AS17971).

The aim of this study is to increase transparency about internet

controls in Malaysia and to collect data that can potentially

corroborate rumours and reports of internet censorship events. The

following sections of this report provide information about Malaysia’s

legal environment with respect to freedom of expression, access to

information, and privacy, as well as about cases of censorship and

surveillance that have previously been reported in the country. The

remainder of the report documents the methodology and key findings of

this study.

Background

Malaysia is a multi-ethnic and multicultural country with a population

of around 30 million

as of 2016, situated in the middle of Southeast Asia. Geographically,

Malaysia consists of two parts: Peninsular Malaysia bordering with

Thailand in the north and Singapore in the south, and East Malaysia on

the northern part of the island of Borneo bordering with Indonesia in

the south.

Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy, consisting of 13 states

and 3 federal territories. Malaysia is also multiracial, consisting of

Bumiputras and Muslim Malays that make up the majority

(50.1%)

of the population. Bumiputera status is also accorded to certain

non-Malay indigenous people of East Malaysia. 22.6% of Malaysia’s

population is Chinese, while 6.7% is Indian. Ethnicity plays a major

role in Malaysia, as there are a number of rights and privileges

accorded to bumiputeras due to racial economic policies in place in

Malaysia.

Statistics from the 2010 census

show a religious makeup of the population at 61% Muslims, 19.8%

Buddhist, 9.3% Christians and 6.3% Hindu. Religious beliefs mostly

follow ethnic lines. Article 11 of the

Constitution

provides for freedom of religion, but it restricts propagation of any

religious doctrine or belief among Muslims. All Malays however are

Muslim by law, and apostasy is not legally allowed. Islam is a state

religion, and state governments can impose Islamic law on Muslims. The

government only accepts Sunni Islamic beliefs and any other Islamic

beliefs, such as Shia, are not recognized and considered as deviant. The

Government

restricts the

distribution in peninsular Malaysia of Malay-language translations of

the Bible, Christian tapes, and other printed materials.

Politically Malaysia has been governed by single coalition government at

the federal level by the Barisan Nasional (National Front) since independence in 1957.

The National Front is made up of several race based parties dominated by

the Malay ethnic party United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). The

Barisan Nasional Coalition has been in power in all the state

governments since independence, with a few brief periods where it lost

in Eastern States of Kelantan and Sabah. This has resulted in a

government and population that often does not differentiate between the

roles of the elected executive and government. In 2008 however the

political landscape changed when the opposition parties won elections in two of the largest states

by economy in Penang and Selangor. Over a third of the federal

parliamentary seats were also won by the opposition in this election. In

the last elections in 2013, the opposition gained more seats in both

federal and states, while winning the popular vote. This has resulted in

a current parliament that has demanded more accountability from the

executive.

Economically Malaysia has been one of the fastest developing countries in Asia for the past few

decades with a GDP growing on average 6.5 per cent annually from 1957 to

2005. Malaysia is a highly open and competitive, upper-middle income

economy.

In relation to its ASEAN neighbours, with the exception of Singapore,

Malaysia ranks much higher when it comes to the measurement of

corruption. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Malaysia

ranked 50th in 2015. On 2nd July 2015, the Wall Street Journal released

a bombshell by disclosing documents that showed that USD 680 million was transferred to the personal accounts of the Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak

possibly from the 1MDB state-owned investment company. Eventual leaks

and stories over the course of several months finally led to a detailed

public US Department of Justice Kleptocracy department case which traced

how public money totalling USD 3.5 billion was stolen from the Malaysian

citizen.

The implications of 1MDB for governance are far reaching in Malaysia. It

led to the

dismissal

of the Attorney General and transfers of senior investigating staff of

MACC. The Auditor General report from PAC investigation on 1MDB was also

classified under the Official Secrets Act.

During the October-November 2016 parliamentary sessions, discussions on

1MDB and the Department of Justice case have been censored. Despite

parliamentary privilege, MPs discussing 1MDB are called up by police for

sharing information on it.

Network landscape and internet penetration

All internet and mobile services providers in Malaysia are

privately-owned. Overall, Malaysia has 10 different Internet Service

Providers (ISPs) with 4 major mobile operators: DiGi, Maxis, Celcom and

Umobile.

| Mobile Operators/ISPs | Fixed Internet | Mobile Internet |

|---|

| DiGi Telecommunications | | X |

| Maxis Communications | X | X |

| Celcom Axiata | | X |

| Packet One Networks (P1) | X | |

| Yes 4G | | X |

| Tune Talk | | X |

| Telekom Malaysia (TMnet) | X | |

| Time dotcom | X | |

| RED Tone | | X |

| U Mobile | | X |

Internet penetration in Malaysia is currently

72.2% for

households and 91.7% for individual users, while the figures surpass the

population figures for access to the internet on mobile phones. More

than 80% of internet users live in urban areas, and penetration remains

low in less populated states in East Malaysia.

Indicators and internet penetration rates per 100 inhabitants and

households from 2011 to 2016 are illustrated below.

| Year | Population (Million) | Households (‘000) | Broadband | | Cellular Phone | Direct Exchange Line |

|---|

| | | Per 100 Inhabitants | Per 100 Households | Per 100 Households | Per 100 Inhabitants |

| 2011 | 28.7 | 6,675 | 19.4 | 62.3 | 127.7 | 37.3 |

| 2012 | 29 | 6,744 | 21.7 | 66 | 141.6 | 34.4 |

| 2013 | 29.91 | 6,939 | 22.6 | 67.1 | 143.6 | 32.4 |

| 2014 | 30.29 | 7,092 | 31.9 | 70.2 | 148.5 | 30.3 |

| 2015 | 30.68 | 7,483 | 100.4 | 77.3 | 143.8 | 27.9 |

| 2016 | 30.97 | 7,570 | 114.7 | 77.9 | 141.6 | 14.7 |

Source: Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commision

Legal environment

Malaysia’s constitution and Bill of Guarantees provides citizens with

“the right to freedom of speech and expression,” but allows for

limitations to this right. The government exercises tight control over

online media, print, and broadcast media through laws like the

Official Secrets Act

and the Sedition Act.

Under Section 211 of the Communication and Multimedia Act (CMA),

Malaysian authorities can ban content deemed “indecent, obscene, false,

threatening, or offensive,” and the same, under Section 233 of the CMA,

applies to such content shared over the internet.

In 2012, Malaysia’s parliament passed an

amendment

to the 1950 Evidence Act

that holds intermediaries liable for seditious content posted

anonymously on their networks or websites. This would include hosts of

online forums, news outlets, and blogging services, as well as

businesses providing Wi-Fi services. The amendment also holds someone

liable if their name is attributed to the content or if the computer it

was sent from belongs to them, whether or not they were the author. In

2015 the parliament passed an

amendment

to the Sedition Act that added a new section which empowers the court to

issue an order to an authorised officer under the Communications and Multimedia Act

to prevent access to such publications if the perpetrator is not

identified.

Freedom of expression

Freedom of speech and expression is guaranteed under Article 10 of the

Federal Constitution of Malaysia.

In practice, however, this right can be limited by the vague

interpretations of laws that restrict expression in the interest of

national security, safety and public order.

Sedition Act 1948

Malaysia’s Sedition Act can

potentially be used to restrict freedom of expression online. Sections

3(1) and 4(1) of the Act can be used against any form of statement that

contents seditious tendency - to bring hatred, or to excite disaffection

against any Ruler and Government; to promote feelings of ill will and

hostility between different races or classes of the population of

Malaysia; to question any matter, right, status, position, privilege,

sovereignty.

Communication & Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998

Section 211 of the CMA

bans content deemed “indecent, obscene, false, threatening, or

offensive,” and, under Section 233, the same applies to content shared

over the internet.

Evidence Act 1950

Amendments

to Malaysia’s Evidence Act

hold intermediaries liable for seditious content posted anonymously on

their networks or websites. This includes hosts of online forums, news

outlets, and blogging services, as well as businesses providing Wi-Fi

services. The amendment also holds someone liable if their name is

attributed to the content or if the computer it was sent from belongs to

them, whether or not they were the author.

Press freedom

Printing, Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) 1984

The

amendment

of

PPPA

in 2012 expanded its scope and includes ‘publications’ (anything which

by its form, shape or in any manner is capable of suggesting words or

ideas) posted online and plug loopholes.

Official Secrets Act (OSA) 1972

Malaysia’s Official Secrets Act

is a broadly-worded law which carries a maximum penalty of life

imprisonment for actions associated with the wrongful collection,

possession or communication of official information. Any public officer

can declare any material an official secret: a certification which

cannot be questioned in court. The act allows for arrest and detention

without a warrant, and substantially reverses the burden of proof. It

states that “until the contrary is proven,” any of the activities

proscribed under the Act will be presumed to have been undertaken “for a

purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of Malaysia.”

Privacy

Personal Data Protection Act 2010

Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act protects

any personal data collected in Malaysia from being misused. According to

the Act, one must obtain the consent of data subjects before collecting

their personal data or sharing it with third parties. In order for their

consent to be valid, data collectors must provide data subjects with a

written notice of the purpose for the data collection, their rights to

request or correct their data, what class of third parties will have

access to their data, and whether or not they are required to share

their data, and the consequences if they don’t.

Censorship and surveillance

Communications & Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998

Section 211 of the CMA

bans content deemed “indecent, obscene, false, threatening, or

offensive,” and, under Section 233, the same applies to content shared

over the internet.

Prevention of Crime Act (PoCA) 1959

The

amendment

of

PoCA

allows for detention without trial for a period of two years. This order

can be extended to another two years by the Board. A supervision order

allows for a registered person to be attached with an electronic

monitoring device and imposes conditions such as restriction on internet

use or meeting with other registered persons.

Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act (SOSMA) 2012

SOSMA

has replaced the Internal Security Act (ISA) 1960,

which allowed for infinitely renewable detentions without trial. SOSMA

authorizes phone-tapping and communications powers to the government, as

well as an electronic anklet to track the freed detainees of the

Prevention of Terrorism Act (PoTA). More recently, SOSMA has been used

to raid the offices

of human rights defenders.

Prevention of Terrorism Act (PoTA) 2015

PoTA

enables the Malaysian authorities to detain terror suspects without

trial for a period of two years, without judicial reviews of detentions.

Instead, detentions will be reviewed by a special Prevention of

Terrorism Board. Suspected militants will be fitted with electronic

monitoring devices (EMD or electronic anklets) upon their release from

detention.

Previous cases of internet censorship and surveillance

FinFisher

In 2013, Citizen Lab research found evidence of a FinFisher server

running in Malaysia, and later found evidence of Finfisher software

embedded in an election related document. The Malaysian government

neither confirmed nor denied the use of Finfisher.

Hacking Team Surveillance Software

Leaked Hacking Team emails in 2015 revealed

that at least three government agencies, including the Prime Minister’s

department,

bought

Hacking Team’s Remote Control System (RCS): spyware designed to evade

encryption and to remotely collect information from a target’s computer.

The same emails, however, also revealed that the procuring agencies

seemed to lack the technical capacity to use the software.

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) to timeout HTTP requests

Before the 2013 general elections, users were reporting that some

Youtube videos with politically sensitive content were not viewable.

Sinar Project and other researchers independently

found

that unencrypted HTTP requests on two ISPs (Maxis and TMNet) that

matched some URL strings were timing out. Several other URLs with

political content were also found to be affected by a similar block

by running a test that would split the HTTP headers into smaller packets. As it was only

affecting two ISPs and there does not seem to be any specific pattern to

the urls being blocked, it was not conclusive that this was sanctioned

by any government agency.

This same method of censorship was repeated on 16th February 2016, when

users in Malaysia reported that a BBC article covering an

embarrassing meme of a quote from then Prime Minister Najib Razak was

blocked. The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) however

denied

any government involvement.

News outlets blocked

Access to the Sarawak Report website

has been

blocked

by the Malaysian Communications And Multimedia Commission (MCMC) since

July 2015 on the grounds that it may undermine the stability of the

country, as announced on the MCMC’s official Facebook page.

This marks the first official confirmation of blocking of political

websites in Malaysia.

The Malaysian government has blocked at least ten websites, including

online news portals (Sarawak Report,

Malaysia Chronicle, The Malaysian Insider, Asia Sentinel,

Medium) and private blogs, for reporting about

the scandal surrounding Malaysian Prime Minister Najib tun Razak over

his mysterious private dealings with RM2.6 billions.

The suspension of the publishing permit

of the Edge Weekly and the Edge Financial Daily for three months over

the reports on 1MDB and the arrests of Lionel Morais, Amin Iskandar,

Zulkifli Sulong, Ho Kay Tat and Jahabar Sadiq were blatant punishment

and harassment of the mass media and journalists by the Malaysian

government.

Last year, Malaysiakini’s office was

raided over the report

that a deputy public prosecutor was transferred out of the Malaysian

Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) special operations division. On the

same day, the Royal Malaysian Police, aided by the Malaysian

Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), also

visited

The Star headquarters over a similar

report.

Blocking of websites promoting Bersih 4

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC)

blocked four websites for

spreading information on Bersih in August 2015. These websites include

http://bersih.org, http://globalbersih.org, http://www.bersih.org and

http://www.globalbersih.org. This

marked the second confirmation of directive to censor political websites

after Sarawak Report. After the Bersih 4 protests

on 29th and 30th August, the blocking of these sites was lifted soon

thereafter.

Official announcements of blocked sites by MCMC

Over the last year, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia

Commission (MCMC) has officially announced the blocking of numerous

sites. These include sites involved in the propagation of the Islamic State (IS) ideology in the Malay language,

more than 1,000 porn websites,

and hundreds of online gambling sites.

Examining internet censorship in Malaysia

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), in collaboration with Sinar Project, performed a study of internet

censorship in Malaysia. The aim of this study was to understand whether

and to what extent censorship events occurred in Malaysia during the

testing period (between September to November 2016).

The sections below document the methodology and key findings of this

study.

Methodology

The methodology of this study, in an attempt to identify potential

internet censorship events in Malaysia, included the following:

A list of URLs

that are relevant and commonly accessed in Malaysia was created, and

such URLs - along with other URLs

that are commonly accessed around the world - were tested for blocking

based on OONI’s free software tests. Such tests were

run from two local vantage points in Malaysia (AS4788 and AS17971), and

they also examined whether systems that are responsible for censorship,

surveillance and traffic manipulation were present in the tested

network. Once network measurement data was collected from these tests,

the data was subsequently processed and analyzed based on a set of

heuristics for detecting internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

The analysis period started on 24th September 2016 and concluded on 13th

November 2016.

Creation of a Malaysian test list

An important part of identifying censorship is determining which

websites to examine for blocking.

OONI’s software (called

OONI Probe) is designed to examine URLs contained in specific lists

(“test lists”) for censorship. By default, OONI Probe examines the

“global test list”,

which includes a wide range of internationally relevant websites, most

of which are in English. These websites fall under 30 categories,

ranging from news media, file sharing and culture, to provocative or

objectionable categories, like pornography, political criticism, and

hate speech.

These categories help ensure that a wide range of different types of

websites are tested, and they enable the examination of the impact of

censorship events (for example, if the majority of the websites found to

be blocked in a country fall under the “human rights” category, that may

have a bigger impact than other types of websites being blocked

elsewhere). The main reason why objectionable categories (such as

“pornography” and “hate speech”) are included for testing is because

they are more likely to be blocked due to their nature, enabling the

development of heuristics for detecting censorship elsewhere within a

country.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list,

OONI Probe is also designed to examine a test list which is specifically

created for the country that the user is running OONI Probe from, if such

a list exists. Unlike the global test list, country-specific test lists

include websites that are relevant and commonly accessed within specific

countries, and such websites are often in local languages. Similarly to

the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that

fall under the same set of 30 categories,

as explained previously.

All test lists are hosted by the Citizen Lab on

GitHub, supporting OONI

and other network measurement projects in the creation and maintenance

of lists of URLs to test for censorship. Some criteria for adding URLs

to test lists include the following:

The URLs cover topics of socio-political interest within

the country.

The URLs are likely to be blocked because they include sensitive

content (i.e. they touch upon sensitive issues or express political criticism).

The URLs have been blocked in the past.

Users have faced difficulty connecting to those URLs.

The above criteria indicate that such URLs are more likely to be

blocked, enabling the development of heuristics for detecting censorship

within a country. Furthermore, other criteria for adding URLs are

reflected in the 30 categories

that URLs can fall under. Such categories, for example, can include

file-sharing, human rights, and news media, under which the websites of

file-sharing projects, human rights NGOs and media organizations can be

added.

As part of this study, OONI and Sinar Project reviewed the Citizen Lab’s

test list for Malaysia

by adding more URLs to be tested for censorship. The recently added URLs

are specific to the Malaysian context and fall under the following

categories: human rights issues, political criticism, LGBTI, public

health, religion, social networking, and culture. Overall, 400 different URLs

that are relevant to Malaysia were tested as part of this study. In

addition, the URLs included in the Citizen Lab’s global list

(including 1,218 different URLs) were also tested. As such, a total of

1,618 different URLs were tested for censorship in Malaysia as part

of this research.

A core limitation to the study is the bias in terms of the URLs that

were selected for testing. The URL selection criteria included the

following:

Websites that were more likely to be blocked, because their content expressed

political criticism.

Websites of organizations that were known to have previously been blocked and

were thus likely to be blocked again.

Websites reporting on human rights restrictions and violations.

The above criteria reflect bias in terms of which URLs were selected for

testing, as one of the core aims of this study was to examine whether

and to what extent websites reflecting criticism were blocked, limiting

open dialogue and and access to information across the country. As a

result of this bias, it is important to acknowledge that the findings of

this study are only limited to the websites that were tested, and do not

necessarily provide a complete view of other censorship events that may

have occurred during the testing period.

OONI network measurements

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is a free software project that

aims to increase transparency about internet censorship and traffic

manipulation around the world. Since 2011, OONI has developed multiple

free and open source software tests designed to

examine the following:

Blocking of websites.

Detection of systems responsible for censorship and traffic manipulation.

Reachability of circumvention tools (such as Tor, Psiphon, and Lantern) and

sensitive domains.

As part of this study, the following OONI software tests were run from two

local vantage points (AS4788 and AS17971) in Malaysia:

The web connectivity test was run with the aim of examining whether a

set of URLs (included in both the “global test list”,

and the recently updated “Malaysian test list”)

were blocked during the testing period and if so, how. The Vanilla Tor

test was run to examine the reachability of the Tor network, while the Meek Fronted Requests

test was run to examine whether the domains used by Meek (a type of

Tor bridge) work in tested

networks.

The HTTP invalid request line and HTTP header field manipulation tests

were run with the aim of examining whether “middle boxes” (systems

placed in the network between the user and a control server) that could

potentially be responsible for censorship and/or surveillance were

present in the tested network.

The sections below document how each of these tests are designed for the

purpose of detecting cases of internet censorship and traffic

manipulation.

Web connectivity

This test

examines

whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it attempts to

determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering, TCP

connection RST/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy. Specifically,

this test is designed to perform the following:

Resolver identification

DNS lookup

TCP connect

HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step,

which is performed only over the network of the user) both over a

control server and over the network of the user. If the results from

both networks match, then there is no clear sign of network

interference; but if the results are different, the websites that the

user is testing are likely censored.

Further information is provided below, explaining how each step

performed under the web connectivity test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a

host name (e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16).

Internet Service Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers

which map IP addresses to hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs

map the requested host names to the wrong IP addresses, which is a form

of tampering.

As a first step, the web connectivity test attempts to identify which

DNS resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS

query to special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose

the IP address of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the web connectivity test

has identified the DNS resolver of the user, it then attempts to

identify which addresses are mapped to the tested host names by the

resolver. It does so by performing a DNS lookup, which asks the resolver

to disclose which IP addresses are mapped to the tested host names, as

well as which other host names are linked to the tested host names under

DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The web connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested

websites by attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port

443 for URLs that begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that

were identified in the previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the web connectivity test

connects to tested websites (through the previous step), it sends

requests through the HTTP protocol to the servers which are hosting

those websites. A server normally responds to an HTTP GET request with

the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both

over a control server and over the network of the user, the collected

results are then compared with the aim of identifying whether and how

tested websites are tampered with. If the compared results do not

match, then there is a sign of network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are

identified:

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host

names) do not match.

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established

over the network of the user.

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP

status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

The body length of compared websites (over the control server and the network of

the user) differs by some percentage

The HTTP headers names do not match

The HTML title tags do not match

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a

local ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to

them geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network

tampering, but merely for the purpose of providing users with localized

content or faster access to websites. As a result, some false positives

might arise in OONI measurements. Other false positives might occur when

tested websites serve different content depending on the country that

the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return

failures even though they are not tampered with.

HTTP invalid request line

This

test

tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which

could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid

HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an

invalid field count and a huge request method – to an echo service

listening on the standard HTTP port. An echo service is a very useful

debugging and measurement tool, which simply sends back to the

originating source any data it receives. If a middle box is not present

in the network between the user and an echo service, then the echo

service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user,

exactly as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic

manipulation in the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid

HTTP request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may

trigger an error and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s

server. Such errors indicate that software for traffic manipulation is

likely placed in the tested network, though it’s not always clear what

that software is. In some cases though, censorship and/or surveillance

vendors can be identified through the error messages in the received

HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has previously

detected the use

of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in networks across

multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially

occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly

sophisticated censorship and/or surveillance software that is

specifically designed to not trigger errors when receiving invalid HTTP

request lines like the ones of this test. Furthermore, the presence of a

middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as

they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

This

test

also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”)

which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the

internet. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a

server, and a server’s response to a client’s request. Every time a user

connects to a server, the user (client) sends a request through the HTTP

protocol to that server. Such requests include “HTTP headers”, which

transmit various types of information, including the user’s device

operating system and the type of browser that is being used. If Firefox

is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP

request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a

Windows operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP

headers that have variations in capitalization. In other words, this

test sends HTTP requests which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP

headers. Such requests are sent to a backend control server which sends

back any data it receives. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as

they were sent, then there is no visible presence of a “middle box” in

the network that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance

and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present in

the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that

are sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a

backend control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate

whether software – which could be responsible for traffic manipulation –

is present in the tested network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical

instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is

specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it

receives them. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not

necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used

in networks for caching purposes.

Vanilla Tor

This test examines

the reachability of the Tor network,

which is designed for online anonymity and censorship circumvention.

The Vanilla Tor test attempts to start a connection to the Tor network.

If the test successfully bootstraps a connection within a predefined

amount of seconds (300 by default), then Tor is considered to be

reachable from the vantage point of the user. But if the test does not

manage to establish a connection, then the Tor network is likely blocked

within the tested network.

Meek Fronted Requests

This test examines whether the domains used by Meek (a type of Tor bridge) work in tested networks.

Meek is a pluggable transport which uses non-blocked domains, such as

google.com, awsstatic.com (Amazon cloud infrastructure), and

ajax.aspnetcdn.com (Microsoft azure cloud infrastructure) to proxy its

users over Tor to blocked websites,

while hiding both the fact that they are connecting to such websites and

how they are connecting to them. As such, Meek is useful for not only

connecting to websites that are blocked, but for also hiding which

websites you are connecting to.

Below is a simplified explanation of how this works:

[user] → [https://www.google.com] → [Meek hosted on the cloud] → [Tor]

→ [blocked-website]

The user will receive a response (access to a blocked website, for

example) from cloud-fronted domains, such as google.com, through the

following way:

[blocked-website] → [Tor] → [Meek hosted on the cloud]

→ [https://www.google.com] → [user]

In short, this test does an encrypted connection to cloud-fronted

domains over HTTPS and examines whether it can connect to them or not.

As such, this test enables users to check whether Meek enables the

circumvention of censorship in an automated way.

Data analysis

Through its data pipeline, OONI

processes all network measurements that it collects, including the

following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from

which the user is running OONI Probe tests from, by automatically

searching for it based on the user’s IP address through the MaxMind GeoIP database. The collection of

country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as it enables

OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify where

network interferences take place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which

corresponds to the network that a user is running OONI Probe tests from.

The collection of the ASN is useful to OONI’s research because it

reveals the specific network provider (such as Vodafone) of a user. Such

information can increase transparency in regards to which network

providers are implementing censorship or other forms of network

interference.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run. This

information helps OONI evaluate when network interferences occur and to

compare them across time.

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not deliberately collect or store users’ IP addresses. In

fact, OONI takes measures to remove users’ IP addresses from the

collected measurements, to protect its users from potential risks.

However, OONI might unintentionally collect users’ IP addresses and

other potentially personally-identifiable information, if such

information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of

measurements. This, for example, can occur if the tested websites

include tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s

network location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types

of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed

through its git repository,

and details about what collected network measurements entail can be

viewed through OONI Explorer or through

OONI’s public list of measurements.

OONI processes the above types of data with the aim of deriving meaning

from the collected measurements and, specifically, in an attempt to

answer the following types of questions:

Which types of OONI tests were run?

In which countries were those tests run?

In which networks were those tests run?

When were tests run?

What types of network interference occurred?

In which countries did network interference occur?

In which networks did network interference occur?

When did network interference occur?

How did network interference occur?

To answer such questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to process data

which is automatically sent to OONI’s measurement collector by default.

The initial processing of network measurements enables the following:

Attributing measurements to a specific country.

Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were run for their

collection.

Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the latter

indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of heuristics for

DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for HTTP blocking.

Identifying the presence of “middle boxes” (such as Blue Coat) within tested

networks.

However, false positives and false negatives emerge within the processed

data due to a number of reasons. As explained previously (section on

“OONI network measurements”),

DNS resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often provide users

with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. While this

may appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done with the

intention of providing users with faster access to websites. Similarly,

false positives may emerge when tested websites serve different content

depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the

cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered

with.

Furthermore, measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might

actually be due to temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not

conclusively be a sign of network interference. It is therefore

important to test the same sets of websites across time and to

cross-correlate data, prior to reaching a conclusion on whether websites

are in fact being blocked.

Since block pages differ from country to country and sometimes even from

network to network, it is quite challenging to accurately identify them.

OONI uses a series of heuristics to try to guess if the page in question

differs from the expected control, but these heuristics can often result

in false positives. For this reason OONI only says that there is a

confirmed instance of blocking when a block page is detected.

OONI’s methodology for detecting the presence of “middle boxes” -

systems that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and

traffic manipulation - can also present false negatives, if ISPs are

using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to

not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them, or to not

trigger error messages when receiving invalid HTTP request lines. It

remains unclear though if such software is being used. Moreover, it’s

important to note that the presence of a middle box is not necessarily

indicative of censorship or traffic manipulation, as such systems are

often used in networks for caching purposes.

Upon collection of more network measurements, OONI continues to develop

its data analysis heuristics, based on which it attempts to accurately

identify censorship events.

Findings

As part of this study, hundreds of thousands of network measurements from two

local vantage points (AS4788 and AS17971) in Malaysia collected between

24th September 2016 and 13th November 2016 were analyzed.

Upon analysis of the collected data, the findings illustrate that 39

different websites were blocked based on DNS injections of block

pages during the testing period. These sites fall under the following

categories: news media, political criticism, file-sharing, hosting and

blogging platforms, online dating, religion, pornography, and gambling.

The table below includes all of the websites that were

found to be blocked

based on DNS injections of block pages.

| Blocked websites | Categories | First measured | First blocked | Last blocked | Last measured |

|---|

http://adultfriendfinder.com | Online Dating | 2016-09-24 3:55:08 | 2016-09-24 3:55:08 | 2016-11-13 22:39:44 | 2016-11-13 22:39:44 |

http://beeg.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 3:55:26 | 2016-09-24 3:55:26 | 2016-11-13 22:39:53 | 2016-11-13 22:39:53 |

http://extratorrent.cc | File-sharing | 2016-11-10 0:02:37 | 2016-11-10 0:03:42 | 2016-11-13 0:03:34 | 2016-11-13 0:03:34 |

http://jinggo-fotopages.blogspot.my/ | Political Criticism | 2016-11-10 1:11:18 | 2016-11-10 1:11:18 | 2016-11-13 1:18:17 | 2016-11-13 1:18:17 |

http://malaysia-chronicle.com | Political Criticism | 2016-09-24 3:32:58 | 2016-09-24 3:32:58 | 2016-11-13 22:26:26 | 2016-11-13 22:26:26 |

http://manhub.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 3:59:53 | 2016-09-24 3:59:53 | 2016-11-13 22:41:46 | 2016-11-13 22:41:46 |

http://pornhub.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:01:41 | 2016-09-24 4:01:41 | 2016-11-12 22:42:19 | 2016-11-13 22:42:16 |

http://redtube.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:02:06 | 2016-09-24 4:02:06 | 2016-11-13 22:42:28 | 2016-11-13 22:42:28 |

http://syedsoutsidethebox.blogspot.my/ | Political Criticism | 2016-11-10 1:11:16 | 2016-11-10 1:11:16 | 2016-11-13 1:18:14 | 2016-11-13 1:18:14 |

http://tabunginsider.blogspot.my/ | Political Criticism | 2016-11-10 1:11:13 | 2016-11-10 1:11:13 | 2016-11-13 1:18:13 | 2016-11-13 1:18:13 |

http://thepiratebay.org | File-sharing | 2016-09-24 4:03:00 | 2016-09-24 4:03:00 | 2016-11-13 22:42:44 | 2016-11-13 22:42:44 |

http://www.888casino.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:05:18 | 2016-09-24 4:05:18 | 2016-11-13 0:08:58 | 2016-11-13 22:43:49 |

http://www.89.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:05:19 | 2016-09-25 4:05:11 | 2016-11-13 22:43:49 | 2016-11-13 22:43:49 |

http://www.ashemaletube.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:07:28 | 2016-09-24 4:07:28 | 2016-11-13 22:44:57 | 2016-11-13 22:44:57 |

http://www.asiasentinel.com | News Media | 2016-09-24 3:49:08 | 2016-09-24 3:49:08 | 2016-11-13 22:33:31 | 2016-11-13 22:33:31 |

http://www.belmont.ag | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:10:13 | 2016-09-24 4:10:13 | 2016-11-13 22:45:27 | 2016-11-13 22:45:27 |

http://www.betfair.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:10:23 | 2016-09-24 4:10:23 | 2016-11-13 22:45:29 | 2016-11-13 22:45:29 |

http://www.carnivalcasino.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:13:39 | 2016-09-24 4:13:39 | 2016-11-12 22:46:31 | 2016-11-13 22:46:36 |

http://www.casinotropez.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:13:41 | 2016-09-24 4:13:41 | 2016-11-13 22:46:41 | 2016-11-13 22:46:41 |

http://www.clubdicecasino.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:14:34 | 2016-09-24 4:14:34 | 2016-11-13 22:47:19 | 2016-11-13 22:47:19 |

http://www.europacasino.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:17:45 | 2016-09-24 4:17:45 | 2016-11-13 22:49:53 | 2016-11-13 22:49:53 |

http://www.goldenrivieracasino.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:20:34 | 2016-09-24 4:20:34 | 2016-11-13 22:52:00 | 2016-11-13 22:52:00 |

http://www.hustler.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:21:36 | 2016-09-24 4:21:36 | 2016-11-13 22:52:34 | 2016-11-13 22:52:34 |

http://www.livejasmin.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:32:04 | 2016-09-24 4:32:04 | 2016-11-13 22:55:28 | 2016-11-13 22:55:28 |

http://www.roxypalace.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:41:19 | 2016-09-24 4:41:19 | 2016-11-13 23:01:30 | 2016-11-13 23:01:30 |

http://www.sarawakreport.org | News Media | 2016-09-24 3:49:15 | 2016-09-24 3:49:15 | 2016-11-13 22:33:33 | 2016-11-13 22:33:33 |

http://www.sarawakreport.org/2016/04/the-simple-silver-bullet-solution-to-1mdb-malaysias-financial-woes-sack-najib/ | News Media | 2016-09-24 3:51:03 | 2016-09-24 3:51:03 | 2016-11-13 1:15:58 | 2016-11-13 1:15:58 |

http://www.sarawakreport.org/tag/1mdb | News Media | 2016-09-24 3:51:00 | 2016-09-24 3:51:00 | 2016-11-13 1:15:57 | 2016-11-13 1:15:57 |

http://www.sex.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:42:12 | 2016-09-24 4:42:12 | 2016-11-13 23:02:11 | 2016-11-13 23:02:11 |

http://www.spinpalace.com | Gambling | 2016-09-24 4:43:02 | 2016-09-24 23:02:44 | 2016-11-13 23:02:49 | 2016-11-13 23:02:49 |

http://www.themalaysianinsider.com | News Media | 2016-09-24 3:47:22 | 2016-09-24 3:47:22 | 2016-11-13 22:32:39 | 2016-11-13 22:32:39 |

http://www.thereligionofpeace.com | Religion | 2016-09-24 3:49:29 | 2016-09-24 3:49:29 | 2016-11-13 1:14:02 | 2016-11-13 1:14:02 |

http://www.wetplace.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:48:34 | 2016-09-24 4:48:34 | 2016-11-13 23:05:43 | 2016-11-13 23:05:43 |

http://www.worldsex.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:49:57 | 2016-09-24 4:49:57 | 2016-11-13 23:06:26 | 2016-11-13 23:06:26 |

http://xhamster.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:50:56 | 2016-09-24 4:50:56 | 2016-11-13 23:06:59 | 2016-11-13 23:06:59 |

http://xvideos.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:50:56 | 2016-09-24 23:06:57 | 2016-11-13 0:49:33 | 2016-11-13 23:06:59 |

http://youjizz.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:51:03 | 2016-09-24 4:51:03 | 2016-11-13 23:07:06 | 2016-11-13 23:07:06 |

http://youporn.com | Pornography | 2016-09-24 4:51:07 | 2016-09-24 4:51:07 | 2016-11-13 23:07:07 | 2016-11-13 23:07:07 |

https://medium.com | Hosting and Blogging platforms | 2016-09-24 3:49:13 | 2016-09-24 3:49:13 | 2016-11-13 22:33:33 | 2016-11-13 22:33:33 |

https://thepiratebay.se | File-sharing | 2016-09-24 4:51:47 | 2016-09-24 23:07:17 | 2016-11-13 23:07:28 | 2016-11-13 23:07:28 |

https://torrentz.eu | File-sharing | 2016-09-24 4:51:49 | 2016-09-25 6:06:53 | 2016-11-12 23:07:42 | 2016-11-13 23:07:29 |

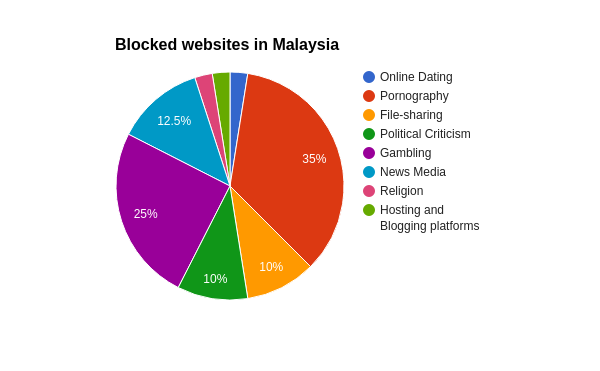

The chart below illustrates that porn, gambling and news websites were

found to be blocked the most. Similarly, torrenting sites and websites

expressing political criticism also presented relatively high

percentages of blocking from the sites that were found to be blocked.

Recently, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC)

announced

the blocking of 5,044 websites for various offenses under the Malaysia Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998.

According to Malaysia’s Deputy Communications and Multimedia Minister,

most of these websites include pornography, while others include

gambling, piracy, unregistered medicine, and counterfeit products. Some

of these sites might be included in the

findings of this

study, but the blocking of news outlets that covered the 1MDB scandal appears to be

politically motivated.

In the following subsections we dive into each of these categories to

examine what was found to be blocked in Malaysia during the testing

period.

A major political scandal erupted in

Malaysia in 2015 when the country’s Prime Minister was accused of

corruption and embezzlement, resulting in the blocking of independent news websites.

1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) is a

strategic development company, wholly owned by the Government of

Malaysia, that was established to drive the country’s economic

development through global strategic partnerships and foreign direct

investment. The scandal

first broke out when the Wall Street Journal

reported

that it had seen a paper trail that allegedly traced close to $700m to

the personal bank accounts of Malaysia’s Prime Minister. But negative

attention towards the 1MDB had already been drawn since early 2015,

after it missed payments that it owed to

banks and bondholders.

Two Malaysian news websites, the Malaysian

Insider and Sarawak

Report, were reportedly

blocked in February

2015 for covering the scandal. Sarawak Report mirrored its site, and

that was

blocked

too. The government justified the

blocking on the grounds

of “maintaining peace, stability, and harmony in the country”. A month

later, the Malaysian Insider shut down

completely, despite having gained popularity in the country. And

according to our testing, both sites remain blocked in Malaysia to

date.

Similarly, we also found the website of Asia Sentinel, another news

outlet that heavily

covered

Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal, to be

blocked.

Asia Sentinel is an independent media outlet that reports on news from

all across Asia. In 2014, Asia Sentinel won the 2014 SOPA Award for Excellence in Explanatory

Journalism. As part of our testing,

www.asiasentinel.com consistently

returned a block page.

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) has

justified

the blocking of these sites on the grounds of national security under

Section 233 of the 1998 Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA).

Blocked news websites

http://www.asiasentinel.comhttp://www.sarawakreport.orghttp://www.sarawakreport.org/2016/04/the-simple-silver-bullet-solution-to-1mdb-malaysias-financial-woes-sack-najib/http://www.sarawakreport.org/tag/1mdbhttp://www.themalaysianinsider.com

Political Criticism

Several political blogs were found to be blocked as part of our study. Amongst them, a satirical photo blog that specializes in Malaysian politics and which covered the 1MDB scandal

returned block pages every time we tested it. Similarly, a

blog that serves as a

publishing platform for short articles, information, and thoughts that

are “outside the box” was also found to be blocked based on the DNS

injection of a block page.

Interestingly, a blog which

published documents pertaining to the mismanagement of public funds in

relation to the 1MDB scandal was also found to be blocked. This blog

also expresses frustration with how funds of the Malaysian Pilgrims

Funds Board (Tabung Haji) were misappropriated when used to bail out the

1MDB. Malaysia’s Prime Minister has denied these allegations,

stating

“Why would we use public money to bail out 1MDB? That is not a mark of

a responsible government.” Yet, this blog remains blocked according to

our testing.

Malaysia Chronicle is a news

outlet that provides citizens with the opportunity to “speak up on

politics, business, and social”. Most of its articles express political

criticism and according to our findings, this site remained

blocked

throughout the testing period.

Blocked sites expressing political criticism

http://jinggo-fotopages.blogspot.my/http://malaysia-chronicle.comhttp://syedsoutsidethebox.blogspot.my/http://tabunginsider.blogspot.my/

Religion

While Malaysia’s constitution guarantees freedom of religion, Islam is

the country’s state religion. As part of this study, we found a

site expressing heavy criticism

towards Islam to be

blocked

in Malaysia.

This site keeps track of and enumerates the amount of terror attacks,

suicide blasts, and deaths and injuries worldwide. It also publishes

articles that document violence against non-Muslims in Bangladesh and

other countries around the world.

In the Malaysian context, this site can be viewed as inciting hatred

towards Islam and its blocking can therefore be justified under the

1948 Sedition Act,

which prohibits the incitement of hatred towards any religion.

Blocked site criticising Islam

Hosting and Blogging platforms

Once the Sarawak Report was blocked for covering the 1MDB scandal,

it subsequently attempted to have its articles published on medium.com,

one of the world’s most popular online publishing platforms. However,

this resulted in the blocking of medium.com

for hosting stories by Sarawak Report.

OONI data collected as part of this study shows that medium.com was

blocked

throughout the testing period.

Blocked blogging platform

File-sharing

Two different versions of The Pirate Bay, a site that facilitates

peer-to-peer file-sharing amongst users of the BitTorrent protocol, was

found to be

blocked

as part of our study. Similarly, two other torrenting sites were also

found to be

blocked.

These sites might be part of the thousands of websites that were

recently announced to be blocked by the MCMC

for enabling piracy, which is viewed as an offense under Malaysia’s 1998 Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA).

Blocked torrenting sites

http://extratorrent.cchttp://thepiratebay.orghttps://thepiratebay.sehttps://torrentz.eu

Online Dating

Adult Friend Finder, one of the world’s most popular online dating

sites, was found to be

blocked

as part of this study. It remains unclear though what the motivation was

behind the blocking of this particular site, and not other popular

dating sites.

Blocked online dating site

Pornography

Pornography is strictly banned in

Malaysia and the censorship of pornographic websites can be

justified

under the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

As part of this study, the following pornographic websites were found to

be blocked.

Blocked porn websites

http://beeg.comhttp://pornhub.comhttp://redtube.comhttp://www.89.comhttp://www.ashemaletube.comhttp://www.hustler.comhttp://www.livejasmin.comhttp://www.sex.comhttp://www.wetplace.comhttp://www.worldsex.comhttp://xhamster.comhttp://xvideos.comhttp://youjizz.comhttp://youporn.com

Gambling

Malaysia strictly prohibits online gambling. The blocking of gambling

sites can be justified under the Common Gaming Houses Act 1953

(Act 289) and under the Pool Betting Act 1967.

Under Sharia Law, online gambling is considered a serious crime. As part

of this study, we found the following gambling sites to be blocked in

the country.

Blocked gambling sites

http://www.888casino.comhttp://www.belmont.aghttp://www.betfair.comhttp://www.carnivalcasino.comhttp://www.casinotropez.comhttp://www.clubdicecasino.comhttp://www.europacasino.comhttp://www.goldenrivieracasino.comhttp://www.roxypalace.comhttp://www.spinpalace.com

Acknowledgement of limitations

The findings of this study present various limitations, and do not

necessarily reflect a comprehensive view of internet censorship in

Malaysia.

The first limitation is associated with the testing period, which

started on 24th September 2016 and concluded less than two months later,

on 13th November 2016. As such, censorship events which may have

occurred before and/or after the testing period are not examined as part

of this study.

Another limitation to this study is associated to the amount and types

of URLs that were tested for censorship. As mentioned in the methodology

section of this report (“Creating a Malaysian test list”), the criteria

for selecting URLs that are relevant to Malaysia were biased. The URL

selection bias was influenced by the core objective of this study, which

sought to examine whether sites expressing political criticism and

defending human rights were blocked. Furthermore, while a total of 1,618

different URLs were tested for censorship as part of this study, we did

not test all of the URLs on the internet, indicating the possibility

that other websites not included in test lists might have been blocked.

While network measurements were collected from two local vantage

points in Malaysia (AS4788 and AS17971), OONI’s software tests were not

run from all vantage points in the country where different censorship

events might have occurred.

Conclusion

This study provides data that serves as evidence of the DNS blocking of

39 different websites in Malaysia. Since block pages were detected for

all of these sites, their censorship is confirmed and undeniable.

The blocked websites include news outlets, blogs, and a popular

publishing platform (medium.com). These sites were reportedly first blocked in 2015 for

covering the 1MDB scandal and,

according to our

findings, remained

blocked throughout the testing period of this study (24th September 2016

to 13th November 2016). While the blocking of these sites has been

justified

on the grounds of national security under Section 233 of the 1998 Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA),

these censorship events appear to be politically motivated.

Amongst the

blocked

websites, we found a site that

expresses heavy criticism towards Islam. In the Malaysian context, this

site can be viewed as inciting hatred towards Islam and its censorship

can therefore be justified under Malaysia’s Sedition Act 1948

which prohibits the incitement of hatred towards any religion. We also

found a popular online dating site to

be

blocked,

but the motivation and/or legal justification behind its blocking

remains unclear.

As part of our study, we

found

multiple pornographic, gambling, and torrenting sites to be blocked,

which might fall under the thousands of websites that were announced to be blocked

by the MCMC. The censorship of pornography can be legally justified

under the Malaysia Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998,

while the blocking of gambling sites can be justified under the Common Gaming Houses Act

1953

(Act 289) and under the Pool Betting Act 1967.

On a positive note, some previously blocked sites

(Bersih rally websites) were found to be

accessible.

No signs of censorship were detected when examining the accessibility of

social media, censorship circumvention tools and LGBTI websites, and we

did not detect the presence of any “middle boxes” capable of performing

internet censorship. However, this does not mean that censorship

equipment is not present in the country, but just that these particular

tests were not able to highlight its presence.

OONI and Sinar Project encourage transparency around

internet controls to help enhance the safeguard of human rights and

democratic processes.