The State of Internet Censorship in Indonesia

Kay Yen Wong (Sinar Project), Maria Xynou (OONI), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Khairil Yusof (Sinar Project),Tan Sze Ming (Sinar Project)

2017-05-23

Image: Block page in Indonesia

A research study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and Sinar

Project.

Table of contents

Country: Indonesia

OONI tests: Web Connectivity, HTTP Header Field Manipulation, HTTP Invalid Request Line, Facebook Messenger test, WhatsApp test, Vanilla Tor test.

Probed ISPs: Linknet-Fastnet (AS23700), PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia (AS17974), PT Excelcominado Pratama (AS24203), Hutchison CT Telecommunications (AS45727), PT Cyberindo Aditama (AS4787), PT iNterNUX (AS4832), PT Wireless Indonesia (AS18004), Telemedia Dinamika Sarana (AS38750), PT Quantum Tera Network (AS46023), INDOSAT Internet Network Provider (AS4761), PT. Telekomunikasi Selular (AS23693), PT Maxindo Mitra Solusi (AS38320), University of Indonesia (AS3382), PT. Time Excelindo (AS38150), IP Teknologi Komunikasi (AS23699), PT. Eka Mas Republik (AS63859), PT Graha Multimedia Nusantara Indonesia (AS38505), Bogor Agricultural University (AS17553), Internet Madju Abad Millenindo (AS45701), Linknet (AS9905), Biznet Networks (AS17451).

Testing period: 22nd June 2016 to 1st March 2017.

Censorship method: Block pages implemented via DNS hijacking.

Key Findings

New OONI network measurement data collected from 21 local vantage points confirms the blocking of 161 websites in Indonesia between 22nd June 2016 to 1st March 2017. Indonesian ISPs appear to be implementing block pages primarily through DNS hijacking.

Vimeo and Reddit were found to be blocked in some networks in Indonesia, even though their ban was lifted more than two years ago. A popular animal rights site was also found to be blocked , possibly because it was mistaken for a pornographic website due to its domain (peta.xxx). These cases raise the need for oversight , to prevent ISPs from blocking content at their own discretion and to ensure that sites are unblocked after bans are lifted.

Under the MICT’s 2014 decree, however, Indonesian ISPs are granted the authority to ban “negative content” at their own discretion, regardless of whether such sites are included in the MICT’s official Trust Positif blocklists. This excessive authority granted to Indonesian ISPs may explain why many different types of sites were found to be blocked across different networks.

Multiple sites expressing criticism towards Islam were found to be blocked, possibly under Article 156(a) of Indonesia’s Criminal Code which prohibits blasphemy against religions. Even though Indonesia’s government announced that it would primarily be blocking sites hosting pornographic materials and gambling applications, we found numerous other sites to be blocked as well.

These include:

Interestingly enough, we also found sites (web forums and e-commerce sites) that are no longer operational to be blocked nonetheless.

Many of these censorship events indicate that their implementation was influenced by social and cultural norms , especially since the legal justification behind the blocking of many of these sites remains unclear. This raises the need for transparency and accountability to ensure that the implementation of internet censorship is legally proportionate.

Network tampering was detected across 10 different Indonesian ISPs, possibly indicating the presence of middleboxes that could be responsible for internet censorship, surveillance, and traffic manipulation. A middle box was detected in the Telekomunikasi Indonesia (AS17974) network. While it’s unclear if this specific system was used to implement internet censorship, it’s worth emphasizing that most measurements collected from this network presented signs of network tampering, and that this ISP served block pages for many of the sites that were tested as part of this study.

On a positive note, the Tor network, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp appear to have mostly been accessible in Indonesia throughout the testing period.

Introduction

Six months ago, the Indonesian government announced the blocking of 800,000 websites containing pornographic materials and gambling applications.

In an attempt to examine internet censorship in Indonesia, the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) collaborated with Sinar Project on the collection and analysis of network measurements.

The aim of this study is to increase transparency of information controls in Indonesia and to collect data that can potentially corroborate rumours and reports of internet censorship events.

The following sections of this report provide information about Indonesia’s network landscape and internet penetration levels, its legal environment with respect to free of expression, access to information and privacy, as well as about cases of censorship and surveillance that have previously been reported in the country. The remainder of the report documents the methodology and findings of this study.

Background

Indonesia is a presidential republic in Southeast Asia with a population of over 260 million, making it the world’s fourth most populous country. Geographically, it is the largest archipelago consisting of over 17,000 islands, with most of its population concentrated in the major islands of Java and Sumatera. Out of 17,000 islands, only about 6,000 are inhabited, and half of the country’s population resides in Java alone.

Indonesia is ethnically diverse, with over 300 distinct ethnic groups. The majority of its population is comprised of the Javanese (40.1%). The largest non-Javanese groups are the Sundanese (15.5%), ethnic Malays (3.7%), and the Madurese (3%). The Chinese Indonesians are an influential ethnic minority, even though they only comprise 1.2% of the population. There remains considerable resentment and anti-Chinese violence against the Chinese Indonesians on the widely held sentiment that most of Indonesia’s wealth and commerce are dominated by the Chinese, although no credible research exists to support that.

Although Article 28 of the Indonesian constitution provides for freedom of religion, the Indonesian government officially recognises only 6 religions: Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism.

Indonesia is the most populous Muslim majority country, with an estimated 87.2% of the population being Muslim, making up 13% of the world’s total Muslim population. As such, there are consternations about social and religious issues pervading into discussions on policy and governance, marked by the growing divide between Indonesia’s self proclaimed heritage of pluralistic tolerance and the deepening conservatism of Indonesian Islam.

The recent conviction of ethnically Chinese-Christian politician Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, who was charged under Indonesia’s blasphemy laws for his provocative criticisms of a Quranic verse on electing non-Muslim leaders have been a wake-up call on the exploitation of religion by the Islamic State and the political elite in undermining the government and boosting their own prospects.

Indonesia ranks as a corrupt nation, with a Corruption Perceptions Index rating of 37 out of 100 as of 2016, ranking 90 out of 176 countries. Ahok’s conviction and the racially charged anti-Ahok rallies preceding that have played a role in revealing the worrying surge of religious intolerance and fundamentalist Islamic hard-liners who have been allowed to the forefront of national attention. A recent survey revealed that about 80% of Islamic religious teachers across five of Indonesia’s 34 provinces were in support of the implementation of the Sharia law, further concurred by a Pew research study which placed the figure at 72% over all surveyed Indonesian Muslims.

With the threat of terrorism that Indonesia has faced - from the deadly terrorist attacks and bombings by Islamic extremists over the course of Indonesia’s history which remain imprinted in the country’s security landscape, to the ongoing human rights violations and military suppression of Papuan activists from Papuan separatist movements since the 1960s - there is also worry that such challenges may be used as justification by the Indonesian government for the utilisation of surveillance against these “opponents” of national stability.

Network landscape and internet penetration

Due to its unique geography as an archipelago consisting of more than 17,000 islands, Indonesia lacks a centralized internet infrastructure, and has several connections to foreign networks.

Indonesia has over 300 ISPs, though only 35 of them own network infrastructure. The three largest providers in terms of revenue are Telkom, Indosat, and XL-Axiata, and almost 85% of the mobile market is dominated by the 3 major providers. Both Telkom and Indosat are partially state-owned: the government retains 51 and 14 percent ownership of both companies respectively.

| Mobile Operators/ISPs | Fixed Internet | Mobile Internet |

|---|

| Telkom | X | |

| Indosat | X | X |

| XL-Axiata | | X |

| Telkomsel | | X |

| Bakrie Telekom | X | |

| Hutchinson 3 | | X |

| Sampoerna Telekomunikasi Indonesia | | X |

| Smartfren Telecom | | X |

| Pasifik Satelit Nusanta | X | X |

Due to the relative convenience of deploying mobile cellular networks compared with cable infrastructure in Indonesia’s unique geographical island structure, mobile services have seen a , spurred by accelerated customer demand and low cost of adoption.

A 2016 survey by the Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association(APJII) reported around 132.7 million internet users, representing more than 50% of the population, with a majority of 65% of connections coming from the major island of Java, followed by 15.5% from Sumatera, highlighting the uneven development in connectivity and infrastructure. The survey also revealed the ubiquity of mobile devices as the preferred medium of access of Indonesian internet users: 47.6% of users accessed the internet primarily through mobile phones, 50.7% through both computers and mobile devices, and only 1.7% that primarily accessed the internet through computer usage.

Legal environment

Freedom of expression

Articles 27 & 45 of the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law

Articles 27 and 45 of the 2008 ITE law have been used to prosecute individuals who “knowingly and without authority” distribute, transmit, or make accessible electronic information or documents containing (i) material against propriety, (ii) gambling material, (iii) defamatory material, and (iv) material containing extortions or threats. Under Article 45, any individuals satisfying any of the elements could be sentenced to imprisonment of up to 6 years, and/or a maximum fine of 1 billion rupiah. The 2016 amendment to Article 45 reduces the criminal sanction for the crime under Article27(iii) regarding defamation to a maximum imprisonment term of 4 years and a fine of 750 million rupiah, in addition to clarifying that the provision for the dissemination of defamatory material is a crime by complaint.

2013 Law on Civil Society Organizations

The 2013 Civil Society Organizations Law subjects civil society organisations (CSOs) to increased bureaucratic and discriminatory controls, authorizing government screening of all CSOs in the country. The law stipulates CSOs to various prohibitions and obligations to be able to obtain a permit to operate within the country, including prohibiting CSOs from propagating ideologies conflicting with the state ideology of Pancasila , which embraces the five principles of Indonesian nationalism; internationalism; consent or democracy; social prosperity; and belief in one God, thus directly infringing upon the rights of organizations to freedom of religion.

The law places severe limitations on the running of foreign-funded CSOs within the country. Article 52 of the law prohibits CSOs founded by foreign citizens from conducting any intelligence or political activities, or any activities which may “disrupt the stability and integrity” of Indonesia or which may “disrupt diplomatic relations”.

Article 52(g) prohibits the “raising of funds from the Indonesian community”; and (h) “the use of facilities and infrastructures of government agencies and institutions”. Violations of such repressive provisions may result in the dissolution of the CSO.

Press freedom

1999 Press Law

Article 4 of the 1999 Press Law guarantees freedom of the press as a basic human right for every citizen. The law contains many positive stipulations which serve to protect the freedom of the press. 4(2) provides that the national press shall not have censorship or broadcast limitations imposed upon it, while 4(3) provides the national press with the right to seek, acquire, and disseminate ideas and information freely to insure the freedom of the press.

However, the Press Law also contains a number of potentially harmful restrictions on content which may be open to abuse. Article 5 of the law constrains the national press to reporting events and opinions with respect to the religious and moral norms of the public, in accordance with the presumption of innocence. This places restriction on forms of expressions such as legitimate criticisms of religious bodies, which contradicts the stipulation in Article 6 that provides that the national press plays its role in fulfilling the public’s right to know, and in providing criticism, correction and suggestion towards public concerns.

2008 Law on Public Information Openness

The 2008 Law on Public Information Openness guarantees freedom of information as a right for Public Information Requesters, restricted only to Indonesian citizens or legal entities. Under Articles 22 and 35, requests for information require that the name, address and the reason for the request of be provided by requesters. Problematically, the law would enable the possibility of sanitization of requested documents, allowing for the redaction or “blackening” of restricted information while providing access to the rest of the document.

Under the law, criminal sanctions are provided for public officials found to deliberately disregard their obligation to provide and publish public information. However, under Article 51, harsh penalties are also prescribed for any person found to have committed deliberate use of public information “in an unlawful manner”, with violators being liable to imprisonment of up to one year, and a maximum fine of five million rupiah. What is considered to be “against the law”is vaguely defined, and leaves such provisions open to abuse.

Although provisions exist to guarantee the right for freedom of information, implementation remains flawed: A 2012 study revealed structural inefficiencies with the way requests for information were handled by public bodies in Indonesia. Only 46% of 224 information requests had being granted, and participants frequently reported that their requests had been ignored or lost by public authorities.

2011 State Intelligence Law

Article 26 of the 2011 State Intelligence Law penalises individuals for the dissemination of “state secrets”, with an imprisonment of up to 10 years, and a maximum fine of 500,000,000 rupiah. The broad and ambiguous language behind a “state secret” potentially opens up the legislation to abuse, authorizing the Indonesian State Intelligence Agency (BIN) to expansive intelligence gathering efforts against “opponents” deemed to be “harmful to national interests and security”.

Article 32 of the law authorises the State Intelligence Agency to intercept communications without the need for prior court approval.

Privacy

Indonesia lacks specific laws governing the right to privacy. However, Article 28(g) of the Indonesian Constitution provides for the rights to “protection” and the right to “feel secure”.

Indonesia also lacks a specific framework for personal data protection, although provisions for the protection of personal data are scattered across various pieces of legislation, from the 1999 Telecommunications Law, to the 2014 Medical Personnel Law. A draft regulation on the Protection of Personal Data in Electronic Systems was published in 2015, though it has yet to be passed.

Right to be Forgotten (Article 26 of 2016 Amendment of ITE)

A provision was added to Article 26 of the 2016 Amendment of the Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law regulating that Electronic System Operators (a) provide a mechanism to remove irrelevant information or electronic data, and that they (b) remove all electronic information or electronic records under their control according to a court order at the initiation of a relevant person. Though this seems to provide individuals with an element of privacy protection, the amendment lacks specifics on the circumstances in which electronic information may be deemed ‘irrelevant’, nor the criteria to be considered a ‘relevant person’.

Concerns have been raised over the potential for misuse in a statement by the Secretary General of the Alliance of Independent Journalists, which argues that the provision could be a potential threat to press freedom, as “anyone may request a court order with impunity to erase negative news concerning them in digital media”.

Censorship and surveillance

Bill on Pornography 2008

The 2008 Bill on Pornography prohibits the creation, dissemination, or consumption of pornographic material. The bill presents a loose definition of what constitutes pornography, to the point of criminalizing actions such as the kissing of lips in public, the display of sensual parts of the body (defined in Article 4 as the genitals, buttocks, hips, thighs, navel and female breasts), or any form of art and cultural expression perceived to be explicit. Section 4:1a of the bill explicitly prohibits the action of, or any writing/audio-visual presentation of sexual activities involving same sex relations. The bill is routinely utilised in the censorship of LGBT content on the internet.

Article 40 of the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law

Article 40 of the ITE broadly dictates that the government protect the public interest from any misuse of Electronic Information and Transactions which are deemed as threats against the public interest and which could offend public order.

The 2016 amendment widens the authority of the government with the addition of 2 sub-paragraphs under Article 40 stipulating that the government is authorized to take preventative actions against the dissemination of electronic information and documents containing content violating applicable laws, such as hate speech, defamatory material, or immoral content. The amendment enhances the scope of the government in monitoring electronic information, authorizing them to terminate access to content deemed to fall under such criteria.

Reported cases of internet censorship and surveillance

This section of the report includes a few cases of internet censorship and surveillance in Indonesia, as reported over the last years.

Official announcement of blocked sites by the MICT

As of December 2016, the Indonesian Ministry of Information and Communication (MICT) has announced the blocking of 800,000 websites, the majority of which contain pornographic materials and gambling applications. The sites were blocked under a 2014 Ministerial Regulation which formalized the use of Trust Positif (a filtering application that has been operational since 2010) as the government’s official “blocking service provider”, authorizing the government to restrict websites containing “negative content”, such as pornography. Trust Positif’s blocklists also include LGBT content, radicalism, hate speech, and fraud.

Censorship of LGBT content

On February 12th 2016, broadcasting bans on the airing of LGBT content on television and radio were issued by the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) for the violation of the Broadcasting Code of Conduct(P3) and the Broadcasting Program Standards (SPS), following a discussion at the Central KPI office involving the KPI and the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI).

On March 3rd 2016, the Indonesian Parliamentary Commission for Defense, Foreign Affairs and Information (Commission I), posed recommendations to the MICT for the tightening of controls over the broadcasting of LGBT content, suggesting that the MICT and the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission(KPI) shut down sites promoting or propagating LGBT content, which the MICT has publically agreed to comply with. The MICT has also attempted to impose such discriminatory guidelines on social media and communication apps: public complaints and an advisory discussion panel by the MICT on controversial stickers conveying LGBT themes on the LINE messaging app ultimately led to the removal of the stickers from LINE’s store, at the MICT’s request.

Censorship of Papuan based news sites

Despite Indonesian president Joko Widodo’s lifting of decades-long media restrictions on foreign journalists which prevented them from travelling to the politically sensitive provinces of Papua and West Papua in 2015, SuaraPapua.com, a prominent news site covering human rights violations in Papua, was found to be blocked by the Indonesian government in November 2016 for containing “negative content” under existing Indonesian law. In April 2017, 5 Papuan based sites reporting on human rights violations in Papua were also discovered to be blocked by the MICT without prior notice.

Excessive authority of ISPs

Although the 2008 Bill on Pornography and the 2008 ITE law have routinely been used for the censorship of websites, a 2014 decree by the MICT granting Indonesian ISPs the authority to ban negative content at their discretion is the root of the uneven and widespread blocking amongst ISPs. Often, the blocking of sites falls under the initiative of major provider and state-owed Telkom, regardless of whether the site is blocked under the MICT’s Trust Positif database. This has been the cause for the uneven blocking of prominent sites by one or more ISPs, such as Vimeo, Netflix, Imgur and Reddit.

Hacking Team Surveillance Software

Leaked Hacking Team emails from 2015 revealed a correspondence between Hacking Team, an Italian spyware company, and a government official from the Indonesian National Encryption Body (Lembaga Sandi Negara) expressing interest in the Hacking Team’s Remote Control System (RCS) surveillance product, in addition to training courses for the technology. The spyware is designed to monitor the communications of internet users, evade encryption and remotely collect information from a target’s computer.

FinFisher

Citizen Lab research from 2015 revealed evidence of FinFisher spyware being deployed by Indonesian government agencies in proxy servers overseas. In one case, a FinFisher server in the U.S. was found to be a proxy for a Finspy master server from Indonesia, obscuring the actual location of the FinFisher master. In another, FinFisher proxy servers found operating in Sydney were traced back to a master server in Indonesia. The research identified Indonesia as an avid user of the intrusive spyware sold exclusively to government agencies for law enforcement and intelligence purposes, identifying the National Encryption Body (Lembaga Sandi Negara) as one specific government user within Indonesia, amongst many other government users in Indonesia using separate deployments of FinFisher. This follows from Citizen Lab research from 2013

which documented 4 command and control servers for FinSpy, an intrusion malware, on IP addresses belonging to Indonesian ISPs Telkom, Biznet, and Matrixnet Global Indonesia.

Examining internet censorship in Indonesia

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), in collaboration with Sinar Project, performed a study of internet censorship in Indonesia. The aim of this study was to understand whether and to what extent censorship events occurred in Indonesia during the testing period.

The sections below document the methodology and findings of this study.

Methodology

The methodology of this study, in an attempt to identify potential internet censorship events in Indonesia, included the following:

- Collection of OONI Probe network measurements

- Data analysis

The analysis period started on 22nd June 2016 and concluded on 1st March 2017.

Collection of OONI Probe network measurements

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is a free software project that aims to increase transparency of internet censorship around the world. Since 2011, OONI has developed multiple free and open source software tests designed to examine the following:

- Blocking of websites;

- Blocking of instant messaging apps (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Telegram);

- Blocking of circumvention tools (such as Tor, Psiphon, and Lantern);

- Presence of systems (“middle boxes”) that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and/or traffic manipulation;

- Speed and performance of networks.

As part of this study, the following OONI software tests were run from 21 local vantage points in Indonesia:

The Web Connectivity test was run with the aim of examining whether a set of URLs (included in both the global test list, and the Indonesian test list) were blocked during the testing period and if so, how. The Vanilla Tor test was run to examine the reachability of the Tor network, while the Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp tests were run to examine the reachability of these instant messaging apps in Indonesia during the testing period.

The HTTP Invalid Request Line and HTTP Header Field Manipulation tests were run with the aim of examining whether “middleboxes” (systems placed in the network between the user and a control server) that could potentially be responsible for censorship and/or surveillance were present in the tested networks.

The sections below document how each of these tests are designed for the purpose of detecting cases of internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

Web Connectivity

This test examines whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it attempts to determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy.

OONI’s Web Connectivity test is designed to examine URLs contained in specific lists (“test lists”) for censorship. By default, Web Connectivity examines the “global test list”, which includes a wide range of internationally relevant websites, most of which are in English. These websites fall under 31 categories, ranging from news media, file sharing and culture, to provocative or objectionable categories, like pornography, political criticism, and hate speech.

These categories help ensure that a wide range of different types of websites are tested, and they enable the examination of the impact of censorship events (for example, if the majority of the websites found to be blocked in a country fall under the “human rights” category, that may have a bigger impact than other types of websites being blocked elsewhere). The main reason why objectionable categories (such as “pornography” and “hate speech”) are included for testing is because they are more likely to be blocked due to their nature, enabling the development of heuristics for detecting censorship elsewhere within a country.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list, Web Connectivity is also designed to examine a test list which is specifically created for the country that the user is running OONI Probe from, if such a list exists. Unlike the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that are relevant and commonly accessed within specific countries, and such websites are often in local languages. Similarly to the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that fall under the same set of 31 categories, as explained previously. All test lists are hosted by the Citizen Lab on GitHub, supporting OONI and other network measurement projects in the creation and maintenance of lists of URLs to test for censorship.

As part of this study, OONI’s Web Connectivity test examined the accessibility of URLs included in both the “global test list” (containing 1,105 URLs) and in the “Indonesian test list” (containing 160 URLs). In total, Web Connectivity tests measured 1,765 URLs for censorship across 21 local vantage points in Indonesia between June 2016 to March 2017.

OONI’s Web Connectivity test is designed to perform the following:

- Resolver identification

- DNS lookup

- TCP connect

- HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step, which is performed only over the network of the user) both over a control server and over the network of the user. If the results from both networks match, then there is no clear sign of network interference; but if the results are different, the websites that the user is testing are likely censored.

Further information is provided below, explaining how each step performed under the web connectivity test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a host name (e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16). Internet Service Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers which map IP addresses to hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs map the requested host names to the wrong IP addresses, which is a form of tampering.

As a first step, the Web Connectivity test attempts to identify which DNS resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS query to special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose the IP address of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the Web Connectivity test has identified the DNS resolver of the user, it then attempts to identify which addresses are mapped to the tested host names by the resolver. It does so by performing a DNS lookup, which asks the resolver to disclose which IP addresses are mapped to the tested host names, as well as which other host names are linked to the tested host names under DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The Web Connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested websites by attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port 443 for URLs that begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that were identified in the previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the Web Connectivity test connects to tested websites (through the previous step), it sends requests through the HTTP protocol to the servers which are hosting those websites. A server normally responds to an HTTP GET request with the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both over a control server and over the network of the user, the collected results are then compared with the aim of identifying whether and how tested websites are tampered with. If the compared results do not match, then there is a sign of network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are identified:

- DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host names) do not match.

- TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established over the network of the user.

- HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

- The body length of compared websites (over the control server and the network of the user) differs by some percentage;

- The HTTP headers names do not match;

- The HTML title tags do not match.

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a local ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network tampering, but merely for the purpose of providing users with localized content or faster access to websites. As a result, some false positives might arise in OONI measurements. Other false positives might occur when tested websites serve different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered with.

HTTP Invalid Request Line

This test tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an invalid field count and a huge request method – to an echo service listening on the standard HTTP port. An echo service is a very useful debugging and measurement tool, which simply sends back to the originating source any data it receives. If a middle box is not present in the network between the user and an echo service, then the echo service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user, exactly as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic manipulation in the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid HTTP request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may trigger an error and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s server. Such errors indicate that software for traffic manipulation is likely placed in the tested network, though it’s not always clear what that software is. In some cases though, censorship and/or surveillance vendors can be identified through the error messages in the received HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has previously detected the use of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in networks across multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated censorship and/or surveillance software that is specifically designed to not trigger errors when receiving invalid HTTP request lines like the ones of this test. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

This test also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the internet. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a server, and a server’s response to a client’s request. Every time a user connects to a server, the user (client) sends a request through the HTTP protocol to that server. Such requests include “HTTP headers”, which transmit various types of information, including the user’s device operating system and the type of browser that is being used. If Firefox is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a Windows operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP headers that have variations in capitalization. In other words, this test sends HTTP requests which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP headers. Such requests are sent to a backend control server which sends back any data it receives. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as they were sent, then there is no visible presence of a “middle box” in the network that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present in the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that are sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a backend control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate whether software – which could be responsible for traffic manipulation – is present in the tested network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

Vanilla Tor

This test examines the reachability of the Tor network, which is designed for online anonymity and censorship circumvention.

The Vanilla Tor test attempts to start a connection to the Tor network. If the test successfully bootstraps a connection within a predefined amount of seconds (300 by default), then Tor is considered to be reachable from the vantage point of the user. But if the test does not manage to establish a connection, then the Tor network is likely blocked within the tested network.

WhatsApp test

This test is designed to examine the reachability of both WhatsApp’s app and the WhatsApp web version within a tested network.

OONI’s WhatsApp test attempts to perform an HTTP GET request, TCP connection and DNS lookup to WhatsApp’s endpoints, registration service and web version over the vantage point of the user. Based on this methodology, WhatsApp’s app is likely blocked if any of the following apply:

- TCP connections to WhatsApp’s endpoints fail;

- TCP connections to WhatsApp’s registration service fail;

- DNS lookups resolve to IP addresses that are not allocated to WhatsApp;

- HTTP requests to WhatsApp’s registration service do not send back a response to OONI’s servers.

WhatsApp’s web interface is likely blocked if any of the following apply:

- TCP connections to web.whatsapp.com fail;

- DNS lookup illustrates that a different IP addresses has been allocated to web.whatsapp.com;

- HTTP requests to web.whatsapp.com do not send back a consistent response to OONI’s servers.

Facebook Messenger test

This test is designed to examine the reachability of Facebook Messenger within a tested network.

OONI’s Facebook Messenger test attempts to perform a TCP connection and DNS lookup to Facebook’s endpoints over the vantage point of the user. Based on this methodology, Facebook Messenger is likely blocked if one or both of the following apply:

- TCP connections to Facebook’s endpoints fail;

- DNS lookups to domains associated to Facebook do not resolve to IP addresses allocated to Facebook.

Data analysis

Through its data pipeline, OONI processes all network measurements that it collects, including the following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from which the user is running OONI Probe tests from, by automatically searching for it based on the user’s IP address through the MaxMind GeoIP database. The collection of country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as it enables OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify where network interferences take place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which corresponds to the network that a user is running OONI Probe tests from. The collection of the ASN is useful to OONI’s research because it reveals the specific network provider (such as Vodafone) of a user. Such information can increase transparency in regards to which network providers are implementing censorship or other forms of network interference.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run. This information helps OONI evaluate when network interferences occur and to compare them across time.

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not deliberately collect or store users’ IP addresses. In fact, OONI takes measures to remove users’ IP addresses from the collected measurements, to protect its users from potential risks.

However, OONI might unintentionally collect users’ IP addresses and other potentially personally-identifiable information, if such information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of measurements. This, for example, can occur if the tested websites include tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s network location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed through its git repository, and details about what collected network measurements entail can be viewed through OONI Explorer or through OONI’s measurement API.

OONI processes the above types of data with the aim of deriving meaning from the collected measurements and, specifically, in an attempt to answer the following types of questions:

- Which types of OONI tests were run?

- In which countries were those tests run?

- In which networks were those tests run?

- When were tests run?

- What types of network interference occurred?

- In which countries did network interference occur?

- In which networks did network interference occur?

- When did network interference occur?

- How did network interference occur?

To answer such questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to process data which is automatically sent to OONI’s measurement collector by default. The initial processing of network measurements enables the following:

- Attributing measurements to a specific country.

- Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

- Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were run for their collection.

- Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the latter indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

- Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

- Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for HTTP blocking.

- Identifying the presence of “middle boxes” within tested networks.

However, false positives emerge within the processed data due to a number of reasons. As explained in the previous section, DNS resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. While this may appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done with the intention of providing users with faster access to websites. Similarly, false positives may emerge when tested websites serve different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered with.

Furthermore, measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might actually be due to temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not conclusively be a sign of network interference. It is therefore important to test the same sets of websites across time and to cross-correlate data, prior to reaching a conclusion on whether websites are in fact being blocked.

Since instances of internet censorship differ from country to country and sometimes even from network to network, it is quite challenging to accurately identify them. OONI uses a series of heuristics to try to examine whether a measurement differs from the expected control, but these heuristics can often result in false positives (as explained in the previous section). As a result, OONI only confirms instances of blocking when block pages are detected.

OONI’s methodology for detecting the presence of “middle boxes” - systems that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and traffic manipulation - can also present false negatives, if ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them, or to not trigger error messages when receiving invalid HTTP request lines. It remains unclear though if such software is being used. Moreover, it’s important to note that the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of internet censorship, as such systems are often used in networks for caching purposes.

OONI continues to develop its data analysis heuristics to identify internet censorship events faster and more accurately.

Findings

As part of this study, network measurements were collected through OONI Probe software tests performed across 21 different local vantage points in Indonesia between 22nd June 2016 and 1st March 2017.

Upon analysis of the collected network measurements, the findings confirm the blocking of 161 websites in Indonesia, and reveal the presence of a middle box in the Telekomunikasi Indonesia network. Network tampering was detected across 10 different ISPs, possibly indicating the presence of middleboxes that could be responsible for internet censorship, surveillance, and traffic manipulation.

Most measurements examining the reachability of the Tor network, WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger were successful, indicating that they were accessible in Indonesia throughout the testing period.

The sections below provide more information pertaining to the blocking of websites in Indonesia and the detection of signs of network tampering.

Blocked websites

Multiple websites were found to be blocked in Indonesia as part of this study. Upon analysis of network measurement data collected through OONI’s Web Connectivity test (performed across 21 local vantage points), we found that Indonesian ISPs served block pages for 161 websites through DNS hijacking .

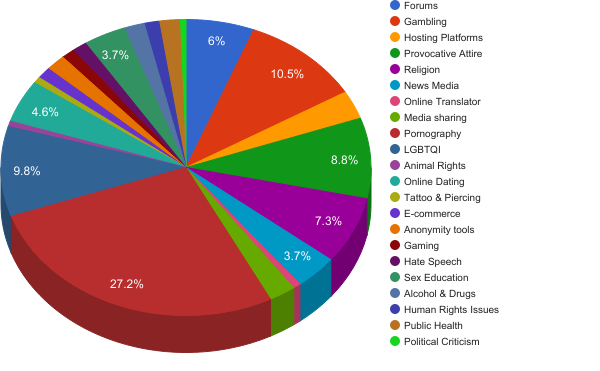

The blocked sites fall under various categories, ranging from online forums, news outlets, and media sharing sites to more provocative categories, such as pornography and online gambling.

The chart below illustrates the types of sites that were confirmed to be blocked as part of this study, based on the amount (percentage) of times that they were found to be blocked throughout the testing period (between June 2016 to March 2017).

The following sections provide further information pertaining to the blocking of sites, as found through this study.

Forums

Ten online forums were found to be blocked in Indonesia, as illustrated in the table below. Interestingly enough, many of these sites were blocked even though they are no longer operational .

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://pass-fan.com/faq.php | 78 | 0 | 13 | 19 |

http://forums.sawomatang.net | 80 | 6 | 1 | 22 |

http://www.gajahnungging.com | 78 | 11 | 19 | 1 |

http://www.asianbookie.com/ch/index.cfm? | 81 | 13 | 14 | 1 |

http://passvipclub.com | 79 | 14 | 16 | 1 |

http://zixzaxteam.net | 72 | 19 | 17 | 1 |

http://ceriwis.us | 77 | 19 | 13 | 1 |

http://ceriwis.us/forumdisplay.php?f=127 | 78 | 19 | 12 | 1 |

http://theoldtigersden.com | 76 | 21 | 11 | 2 |

http://bravo-pass.com | 71 | 25 | 13 | 1 |

The analysis of OONI network measurement data reveals that all ten sites presented block pages which were implemented through DNS hijacking. Many of these sites (except for pass-fan.com/faq.php) also presented HTTP and TCP/IP anomalies as part of the testing, as illustrated through the third column of the table above. The fourth and fifth columns of the table are included to show whether connectivity to the tested sites failed from a control vantage point, as well as whether those sites were found to be accessible as part of other measurements collected from different vantage points in Indonesia.

Interestingly enough, most of these sites are no longer operational, yet Indonesian ISPs appear to be blocking them nonetheless, indicating that the censorship likely started prior to the testing period.

Five news outlets were found to be blocked in Indonesia, as illustrated in the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.mahasiswaonline.info | 80 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

http://www.warungbebas.com | 82 | 13 | 11 | 3 |

http://www.freespeech.org | 88 | 18 | 6 | 0 |

http://crito.jw.lt | 75 | 22 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.reddit.com | 76 | 25 | 7 | 5 |

Reddit, an internationally popular source for sharing online news, presented 76 block pages - implemented through DNS hijacking - as part of our testing. In May 2014, the Indonesian government banned access to reddit.com as part of its crackdown on online pornography. While reddit.com is mostly known as a web forum (rather than as a pornographic site), it may have been blocked for hosting some pornographic content and for enabling heated religious and political debates. Recent OONI network measurement data shows that reddit.com is still blocked in some networks in Indonesia.

Free Speech TV, a U.S. independent news outlet “committed to advancing progressive social change”, was also found to be blocked across Indonesian networks. The site shares daily news programs and independent documentaries covering issues ranging from economic justice and marriage equality to climate change and the cost of war. The motivation and justification behind the blocking of this site remains unclear.

The warungbebas.com domain is currently parked and the domain mahasiswaonline.info has expired, yet they were also found to be blocked as part of this study.

Vimeo is an internationally popular video-sharing website that was found to be blocked in Indonesia, along with three other media sharing sites, as illustrated in the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://thetend.com | 85 | 11 | 11 | 2 |

http://filestube.com | 52 | 18 | 0 | 49 |

http://www.crazyshit.com | 82 | 24 | 9 | 0 |

http://vimeo.com | 83 | 25 | 2 | 7 |

In May 2014, Indonesia’s government banned access to Vimeo under the country’s anti-pornography law (along with vimeo.com and other sites). Instead of applying filters to only block pornography found on the site, service providers blocked access to the entire website. Interestingly enough, even though the ban was lifted in November 2014 (following the election of the country’s new government), vimeo.com was still found to be blocked in Indonesia between June 2016 to March 2017 in some local networks. This indicates three possibilities: (1) Some Indonesian ISPs did not lift the block after November 2014, (2) Some Indonesian ISPs decided to block the site at their own discretion, or (3) Some Indonesian ISPs received new government orders to block the site again.

Similarly to vimeo.com, other sites (as included in the table above) were also found to be blocked as part of this study, possibly on the grounds of sharing content viewed as provocative or obscene.

Gaming

Two online gaming sites were found to be blocked in Indonesia, as illustrated below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://zheg.nastie.co.uk | 71 | 19 | 18 | 1 |

http://9nagatangkas.com | 79 | 19 | 11 | 1 |

The motivation and justification behind the blocking of these sites remains unclear. Possibly, these sites might have been blocked as part of 800,000 websites that were reportedly banned by the Indonesian government, under broader anti-pornography, anti-gambling, and national security laws.

Online Translator

An online translator, systranbox.com was also found to be blocked.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.systranbox.com | 86 | 10 | 0 | 13 |

| This site is likely blocked because it can also be used as a censorship circumvention tool by acting as a web proxy. | | | | |

The following hosting platforms were found to be blocked as part of this study.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.enom.com | 93 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

http://danteam.com | 81 | 16 | 11 | 2 |

http://www.heavens-lounge.net/lounge/ | 78 | 18 | 12 | 1 |

http://mupeng.com/forums/198-18-Tahun-Aza | 76 | 21 | 12 | 1 |

http://ceritacerita.com | 71 | 24 | 15 | 1 |

Tucows (enom.com) offers internet services (such as domains, SSL certificates, cloud hosting, and DNS hosting) - to thousands of business partners and millions of end users around the world. Similarly, HugeDomains.com (ceritacerita.com) offers domain names and was also found to be blocked. The motivation or legal justification behind the blocking of these sites remains unclear.

Three sites that aim to provide online privacy and anonymity were found to be blocked as part of this study.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.ultimate-anonymity.com | 68 | 19 | 19 | 1 |

http://www.anonymizer.com | 76 | 23 | 15 | 1 |

http://anonymouse.org | 83 | 27 | 7 | 1 |

Ultimate Privacy (ultimate-anonymity.com) offers services for online privacy and anonymity, including VPNs, anonymous web hosting, file encryption, and anonymous email services. Anonymizer offers VPN services that route internet traffic through an encrypted tunnel, hiding users’ IP addresses and browsing activities from other third parties (such as governments). Anonymouse enables its users to browse the web and send emails anonymously by transmitting their data through the Anonymouse server, which anonymizes all transmitted data it receives. All three sites were found to be blocked in Indonesia as part of this study.

On a positive note, access to the Tor network - designed to provide users’ with online privacy and anonymity - was mostly found to be accessible in Indonesia.

E-Commerce

Two e-commerce sites were recently found to be blocked in Indonesia, even though they are no longer operational.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.krucil.com/forumdisplay.php?f=5 | 80 | 17 | 11 | 1 |

http://www.ph-store.com | 80 | 18 | 10 | 1 |

Tattoos and Piercing

BME (bmezine.com) is a body modification ezine, featuring tattoos and piercings. This site was found to be blocked in Indonesia, possibly due to its provocative nature.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.bmezine.com | 88 | 17 | 9 | 1 |

Political Criticism

A blog expressing political criticism was found to be blocked in Indonesia.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://indonbodoh.blogspot.com | 73 | 24 | 12 | 1 |

This blog includes a “national song” which appears to be expressing disappointment and criticism towards the country.

Hate Speech

The following sites spreading hate speech were found to be blocked.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.rotten.com | 81 | 20 | 7 | 2 |

http://godhatesfags.com | 86 | 23 | 8 | 1 |

Article 40 of the ITE stipulates that the government is authorized to take preventative actions against the dissemination of electronic information and documents containing content violating applicable laws, such as hate speech, defamatory material, or immoral content.

Religion

Indonesia is the world’s most populous Muslim majority country, with approximately 87.2% of the population identifying as Muslim. The Indonesian Constitution provides “all persons the right to worship according to their own religion or belief”, but officially the government only recognizes six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

Socially and politically, Islam plays a prominent role in Indonesia. The country’s judiciary includes religious courts, along with public courts, administrative courts, military courts, as well as the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Religious courts can cover civil cases as well, such as marriage and inheritance.

Article 156(a) of Indonesia’s Criminal Code prohibits blasphemy against religions and the penalty can include up to five years of imprisonment. Blasphemy is also criminalized under the Presidential Decree No. 1/PNPS/1965 and under provisions in other laws. Recently, Indonesian Christian politician Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was sentenced to two years in prison after being found guilty of committing a criminal act of blasphemy. Numerous other cases have also been reported by Amnesty International, involving the prosecution of individuals for “inappropriate behaviour” in a church, insulting Islam, and for holding atheist beliefs (which are not officially recognized in Indonesia).

In light of such cases, it may not be surprising that sites expressing religious criticism were found to be blocked in Indonesia as part of this study. The table below illustrates all of the sites that served block pages as part of our testing.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://muhammadture.com | 79 | 6 | 12 | 13 |

http://www.prophetofdoom.net | 92 | 12 | 4 | 2 |

http://beritamuslim.wordpress.com | 86 | 16 | 7 | 1 |

http://trulyislam.blogspot.com | 81 | 16 | 11 | 1 |

http://thequran.com | 80 | 18 | 11 | 1 |

http://indonesia.faithfreedom.org/forum/muhammad-bukan-nabi-t1901/ | 78 | 18 | 13 | 1 |

http://kostenlose-toplisten.de | 78 | 18 | 13 | 1 |

http://www.faithfreedom.org | 79 | 19 | 10 | 1 |

http://komiknabimuhammad.blogspot.com | 76 | 20 | 13 | 1 |

http://exmuslim.wordpress.com | 72 | 21 | 16 | 1 |

http://answering-islam.org | 70 | 23 | 16 | 1 |

http://www.answering-islam.org | 82 | 11 | 15 | 1 |

http://indonesia.faithfreedom.org/doc/ | 71 | 26 | 13 | 1 |

Many of the sites included in the table above express criticism or hatred towards Islam, and their blocking may be legally justified under Indonesia’s blasphemy laws. It’s probably worth noting that some of these sites (such as muhammadture.com) are no longer operational, yet Indonesian ISPs were found to be blocking them nonetheless.

Human Rights Issues

The Free Speech Coalition (FSC) is the trade association of the adult entertainment industry based in the United States. According to the organization, its mission involves “fighting to alleviate the social stigma, misinformation, and discriminatory policies that affect those who work in and adjacent to the adult industry”. Its site was found to be blocked in Indonesia, as illustrated in the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.freespeechcoalition.com | 81 | 22 | 10 | 2 |

http://guerrillagirls.com | 84 | 23 | 8 | 0 |

Pornography is prohibited in Indonesia according to Law No. 44 of 2008. While the FSC does not distribute pornography, its site may have been blocked for supporting and defending those who work in the adult entertainment industry.

The Guerilla Girls, on the other hand, are female activist artists who wear gorilla masks in public and “use facts, humor and outrageous visuals to expose gender and ethnic bias, as well as corruption in politics, art, film, and pop culture”. They maintain anonymity while carrying out projects around the world that fight discrimination and support human rights for all people and genders. Their site was found to be blocked in Indonesia during the testing period of this study.

Animal Rights

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) is the largest animal rights organization in the world. In addition to their official site (peta.org), they also host the peta.xxx domain which is interesting because .xxx domains are commonly used for adult entertainment sites. It seems that PETA is hosting this domain to attract larger audiences (such as those seeking pornography) by sharing PETA videos and redirecting them to PETA’s official site.

Upon analysis of network measurements, we found peta.xxx to be blocked in some networks in Indonesia, while PETA’s official site (peta.org) was accessible during the same period. This indicates that Indonesian ISPs likely assumed that peta.xxx was a pornographic site due its domain, and blocked it without realizing that it was actually an animal rights site.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://peta.xxx | 77 | 14 | 0 | 24 |

Our measurements though show that ISPs lifted the block on peta.xxx a few months later, possibly because they noticed that they were censoring an animal rights site instead of pornography.

LGBT

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) rights are not recognized in Indonesia. Section 4:1a of the 2008 Bill on Pornography explicitly prohibits the action of, or any writing/audio-visual presentation of sexual activities involving same sex relations. Provincial governments are allowed to establish certain sharia-based laws which criminalize and pose sanctions for homosexuality. Such bylaws criminalize consensual same-sex acts in certain provinces, and penalties include up to 100 lashes and up to 100 months of imprisonment.

LGBT rights movements have faced fierce opposition from Indonesian authorities. Last year, the country’s Higher Education Minister stated that LGBT people should be barred from university campuses, in response to the creation of the Support Group and Resource Center on Sexuality Studies (SGRC) by University of Indonesia students. The Communications and Information Ministry announced its plan to ban LGBT websites, while the Indonesian Psychiatric Association classified homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgenderism as mental disorders.

In light of the country’s limited tolerance towards LGBT rights, it may not be surprising that we found a number of LGBT sites to be blocked in Indonesia as part of this study. It’s worth noting though that while Indonesian authorities plan to ban such sites, they have not enacted a relevant law yet, which raises questions around the legality of the censorship illustrated in the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://gayindonesiaforum.com | 81 | 13 | 15 | 1 |

http://www.glil.org | 87 | 16 | 7 | 1 |

http://www.bglad.com | 83 | 16 | 14 | 0 |

http://www.tsroadmap.com | 87 | 16 | 4 | 3 |

http://www.gayegypt.com | 86 | 17 | 7 | 5 |

http://www.queernet.org | 87 | 18 | 5 | 2 |

http://www.glbtq.com | 86 | 19 | 6 | 0 |

http://www.gayhealth.com | 84 | 19 | 9 | 1 |

http://www.gay.com | 85 | 19 | 6 | 0 |

http://www.bisexual.org | 85 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

http://www.lesbian.org | 79 | 21 | 13 | 1 |

http://www.samesexmarriage.ca | 85 | 21 | 5 | 1 |

http://transsexual.org | 89 | 24 | 2 | 1 |

http://www.gayscape.com | 81 | 25 | 7 | 1 |

http://www.ifge.org | 80 | 26 | 8 | 0 |

Public Health

Three sites covering health issues were found to be blocked in Indonesia, as illustrated through the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.breastenlargementmagazine.com | 84 | 22 | 8 | 1 |

http://www.altpenis.com | 73 | 27 | 13 | 1 |

http://www.implantinfo.com | 74 | 28 | 9 | 0 |

The blocked sites include a site on men’s reproductive health and sexuality (altpenis.com), which includes articles on AIDS/HIV prevention, STDs, and prostate cancer. The other two blocked sites provide information for breast augmentation and breast implants. The decision to block these sites may have been driven by social and cultural norms, rather than by specific laws that prohibit access to such information.

Sex Education

Amongst the blocked sites, we found sites that promote sexual abstinence and that provide information and advice around sexuality.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.sfsi.org | 86 | 20 | 4 | 2 |

http://www.premaritalsex.info | 84 | 23 | 4 | 1 |

http://www.siecus.org | 81 | 23 | 4 | 1 |

http://www.positive.org | 81 | 24 | 5 | 1 |

http://teenadvice.about.com | 82 | 25 | 7 | 1 |

http://www.itsyoursexlife.com | 63 | 28 | 21 | 2 |

A San Francisco site (sfsi.org) providing “ free, confidential, accurate, non judgmental information about sex ” was amongst those found to be blocked. Others include a site which promotes sexual abstinence (premaritalsex.info) through a series of articles and recommended books, as well as the site of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (siecus.org) which “ advocates for the right of all people to accurate information, comprehensive education about sexuality, and the full spectrum of sexual and reproductive health services ”. The blocked sites also included some providing information around sex education and advice for teenagers.

Online Dating

Popular online dating sites were found to be blocked in Indonesia as well, as illustrated through the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.online-dating.org | 82 | 20 | 8 | 0 |

http://worldsingles.com | 94 | 20 | 1 | 0 |

http://www.date.com | 89 | 20 | 2 | 1 |

http://www.datingdirect.com | 90 | 21 | 2 | 2 |

http://www.mate1.com | 74 | 27 | 11 | 0 |

http://adultfriendfinder.com | 82 | 28 | 11 | 0 |

While the legal justification behind the blocking of these sites remains unclear to us, it’s possible that their blocking was influenced by social, cultural, and religious norms in the country.

Provocative Attire

Five years ago Indonesia’s Minister of Religious Affairs announced a plan to ban mini-skirts as part of “a set of universal criteria” on what constitutes pornography. In other words, the Minister attempted to prohibit Indonesian women from wearing short skirts under the country’s anti-pornography laws and under the assumption that provocative attire leads to rape. Women in Jakarta protested against the proposed ban and while it has not been legally enforced on a nationwide level, some provinces (such as Aceh) prohibit women from wearing tight trousers.

The low tolerance towards provocative attire - or towards what could potentially be viewed as provocative attire - by Indonesian authorities may explain why we found various sites featuring lingerie to be blocked, as illustrated below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.bodylingerie.com | 90 | 5 | 8 | 12 |

http://beritapanasselebritis.blogspot.com | 91 | 11 | 7 | 1 |

http://www.purenudism.net | 88 | 15 | 5 | 1 |

http://novel4u.com | 70 | 17 | 18 | 6 |

http://www.smog.pl | 78 | 18 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.delicates.co.uk | 87 | 20 | 8 | 1 |

http://www.trashy.com | 82 | 20 | 7 | 1 |

http://profilselebryti.blogspot.com | 72 | 21 | 16 | 1 |

http://www.fotoartis.in | 75 | 21 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.flirtylingerie.com | 74 | 21 | 17 | 0 |

http://www.lingeriebowl.com | 75 | 23 | 13 | 0 |

http://www.panties.com | 87 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

http://www.coquette.com | 84 | 24 | 7 | 0 |

http://www.chantelle.com | 79 | 25 | 10 | 1 |

Pornography

Pornography is prohibited in Indonesia according to Law No. 44 of 2008, enforcing imprisonment of up to four years for possessing or downloading pornography, while sexually suggestive performances can lead to 12-year prison sentences. Sharia-based laws also pose sanctions on various sexual acts.

Women’s groups and representatives from cultural associations challenged Indonesia’s anti-pornography law in 2010, arguing that its definition of pornography was too broad, discriminating against women and targeting cultural performances. Indonesia’s Constitutional Court, however, defended the law, ruling that its definition did not violate the constitution.

Earlier this year, the Indonesian government announced the blocking of 800,000 websites, most of them containing pornographic material. As part of this study, we collected network measurement data confirming the blocking of various pornographic websites, as illustrated in the table below.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://www.famouspornstars.com | 90 | 13 | 4 | 5 |

http://www.purextc.com | 88 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

http://conan.xxx | 76 | 15 | 1 | 26 |

http://www.wetplace.com | 80 | 16 | 13 | 1 |

http://www.worldsex.com | 82 | 16 | 9 | 1 |

http://www.lesbiansubmission.com | 78 | 17 | 13 | 2 |

http://www.freegaypornfinder.com | 85 | 18 | 8 | 2 |

http://www.babylon-x.com | 84 | 18 | 5 | 5 |

http://www.fuckingfreemovies.com | 87 | 18 | 7 | 2 |

http://www.hereistheporn.com | 87 | 19 | 8 | 0 |

http://www.freegaypornhdtube.com | 86 | 19 | 7 | 0 |

http://www.youngerbabes.com | 83 | 19 | 8 | 2 |

http://alt.com | 88 | 20 | 8 | 0 |

http://hotgaylist.com | 85 | 21 | 9 | 1 |

http://youporn.com | 77 | 22 | 8 | 2 |

http://www.persiankitty.com | 86 | 22 | 2 | 1 |

http://www.playboy.com | 85 | 23 | 4 | 0 |

http://www.femalestars.com | 83 | 23 | 5 | 1 |

http://rockettube.com | 83 | 24 | 7 | 0 |

http://www.naughty.com | 77 | 24 | 9 | 1 |

http://www.cultoferotica.com | 80 | 24 | 7 | 2 |

http://www.gotgayporn.com | 84 | 24 | 5 | 0 |

http://youjizz.com | 78 | 24 | 8 | 1 |

http://www.hustler.com | 82 | 24 | 8 | 0 |

http://www.livejasmin.com | 75 | 24 | 13 | 0 |

http://manhub.com | 79 | 25 | 11 | 0 |

http://www.sex.com | 81 | 25 | 4 | 2 |

http://www.amateurpages.com | 77 | 25 | 13 | 0 |

http://milfhunter.com | 79 | 26 | 10 | 1 |

http://www.penthouse.com | 86 | 26 | 1 | 0 |

http://www.penisbot.com | 84 | 26 | 1 | 0 |

http://realdoll.com | 77 | 29 | 7 | 1 |

http://gayonthenet.net | 82 | 29 | 7 | 1 |

http://famousnudes.com | 80 | 30 | 9 | 1 |

http://hardsextube.com | 80 | 30 | 8 | 1 |

http://redtube.com | 78 | 31 | 6 | 0 |

http://xvideos.com | 69 | 31 | 8 | 1 |

http://bravotube.net | 67 | 36 | 14 | 0 |

http://pridetube.com | 78 | 36 | 0 | 2 |

http://xhamster.com | 65 | 37 | 7 | 2 |

http://beeg.com | 72 | 38 | 7 | 0 |

http://spankwire.com | 75 | 38 | 4 | 0 |

http://pornhub.com | 64 | 43 | 8 | 1 |

http://www.ashemaletube.com | 64 | 45 | 8 | 0 |

Gambling

All forms of gambling are illegal in Indonesia under the Sharia law. Earlier this year, Indonesian authorities announced the blocking of 800,000 websites, many of which include gambling sites.

As part of our testing and analysis, we found the gambling sites included in the table below to be blocked.

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://pasarbola2.com | 75 | 2 | 15 | 18 |

http://88bola.com | 78 | 9 | 19 | 4 |

http://www.agenbola.com | 81 | 15 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.indoagen.com | 80 | 16 | 12 | 1 |

http://taruhan.org | 81 | 16 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.agent234.com | 78 | 17 | 13 | 1 |

http://bolanaga.com | 82 | 18 | 9 | 1 |

http://bolauntung.com | 79 | 18 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.sportingbet.com | 84 | 19 | 5 | 2 |

http://fifabola.com | 72 | 19 | 19 | 0 |

http://indolucky7.com | 74 | 22 | 13 | 1 |

http://www.betfair.com | 82 | 22 | 10 | 1 |

http://www.partypoker.com | 89 | 22 | 1 | 3 |

http://www.aceshigh.com | 81 | 22 | 9 | 2 |

http://www.pokerstars.com | 88 | 22 | 2 | 1 |

http://bolazoom.com | 76 | 23 | 10 | 1 |

http://www.slotland.com | 76 | 26 | 5 | 1 |

Alcohol and Drugs

Last year Indonesia proposed a bill that would outlaw the production, sale, and consumption of alcohol across the country, including a prison sentence of up to ten years for violators. Currently, alcohol bans are not being enforced on a nationwide level, but these debates may have influenced the decision to block two sites promoting beer (budweiser.com and beer.com).

| Blocked websites | Block pages | HTTP-diff, TCP_IP, HTTP-fail | Control fail | Not blocked |

|---|

http://hightimes.com | 85 | 22 | 8 | 0 |

http://www.budweiser.com | 76 | 25 | 12 | 1 |

http://www.beer.com | 70 | 29 | 14 | 0 |

Capital punishment is enforced in Indonesia for drug trafficking, explaining the blocking of a site promoting the use of cannabis (hightimes.com).

Network tampering

Network tampering was detected across 10 different Indonesian ISPs, possibly indicating the presence of middleboxes that could be responsible for internet censorship, surveillance, and traffic manipulation.

The sections below provide further information, as collected through OONI’s software tests.

OONI’s HTTP Header Field Manipulation test is designed to detect the presence of network components (“middleboxes”) which could be responsible for internet censorship, surveillance, and/or traffic manipulation. By emulating an HTTP request towards a server, this test sends non-canonical HTTP headers that have variations in capitalization. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as they were sent, then there is likely no middle box in the tested network. If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, it will likely normalize the headers or add extra headers to them.

Network measurements collected through OONI’s HTTP Header Field Manipulation test in Indonesia show signs of network tampering, indicating the presence of middleboxes which could be responsible for internet censorship and surveillance.

The table below illustrates the amount of normal and anomalous measurements collected through this test from two local vantage points in Indonesia: Telekomunikasi Indonesia (AS17974) and Linknet-Fastnet (AS23700).

| ASNs | Anomalous measurements | Normal measurements |

|---|

| AS17974 | 43 | 10 |

| AS23700 | 6 | 69 |

The anomalous measurements present signs of network interference, indicating the presence of middleboxes, while normal measurements are those that do not present any signs of network tampering.

It’s worth noting that a middle box was detected in the Telekomunikasi Indonesia (AS17974) network, and that OONI’s HTTP Header Field Manipulation test. While it’s unclear if this specific system was used to implement internet censorship, it’s worth emphasizing that most measurements collected from this network presented signs of network tampering (as illustrated in the table above), and that this provider served block pages for many of the sites that were tested as part of this study.

HTTP Invalid Request Line tests

OONI’s HTTP Invalid Request Line test is designed to detect the presence of network components (“middleboxes”) which could be responsible for internet censorship, surveillance, and/or traffic manipulation. Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an invalid field count and a huge request method - to an echo service listening on the standard HTTP port. If a middle box is not present in the network between the user and the echo service, then the echo service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user, exactly as it received it. If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may trigger an error, which may be sent back to OONI’s servers.

Network measurements collected through OONI’s HTTP Invalid Request Line test in Indonesia show signs of network tampering, indicating the presence of middleboxes which could be responsible for internet censorship and surveillance.

The table below illustrates the amount of normal and anomalous measurements collected through this test from ten local vantage points in Indonesia.

| ASNs | Anomalous measurements | Normal measurements |

|---|

| AS17553 | 1 | 0 |

| AS17974 | 52 | 12 |

| AS18004 | 1 | 6 |

| AS23693 | 1 | 9 |

| AS23700 | 3 | 76 |

| AS24203 | 4 | 2 |

| AS3382 | 2 | 0 |

| AS45727 | 3 | 12 |

| AS4787 | 1 | 4 |

| AS4832 | 1 | 6 |

The anomalous measurements present signs of network interference, indicating the presence of middleboxes, while normal measurements are those that do not present any signs of network tampering.

Interestingly enough, both OONI tests (HTTP Header Field Manipulation and HTTP Invalid Request Line) led to the collection of a large amount of anomalous measurements from Telekomunikasi Indonesia (AS17974), where a middle box was also identified.

Acknowledgement of limitations

The findings of this study present various limitations and do not necessarily reflect a comprehensive view of internet censorship in Indonesia.

The first limitation is associated with the testing period. While thousands of OONI Probe network measurements have been collected from Indonesia since 2014 and continue to be collected on the day of the publication of this report, this study only analyzes network measurements that were collected between 22nd June 2016 to 1st March 2017. This study is limited to this time frame because we aim to examine the most recent censorship events and because there was a significant increase in the collection of network measurements during this period, in comparison to previous months and years. As such, censorship events which may have occurred before and/or after the analysis period are not examined as part of this study.