Examining internet blackouts through public data sources

Maria Xynou, Arturo Filastò

2017-03-28 16:39 UTC

Pulling the plug on the internet is one of the ways that governments around the

world attempt to exert control over the flow of information.

While the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) project has developed numerous software tests for examining different

forms of internet censorship (such as the blocking of websites, instant

messaging apps, and censorship circumvention tools), we currently do not have

tests that are designed to examine internet blackouts, when the internet as a

whole is rendered inaccessible within a location.

Over the last months we received many reports relating to internet blackouts in

various countries around the world. In some of these countries we had probes

running OONI tests, but merely

asserting that an internet blackout had occurred just because we stopped

receiving measurements probably wouldn’t have been accurate. As such, we started

to refer to other public data sources that could help us gain a better

understanding of potential network disruptions in countries where internet

blackouts were reported by locals.

In this post we outline some basics from our methodology when examining internet

blackouts through public data sources.

Identifying data sources

Our main criterion for identifying data sources that can help shed light on

network disruptions is that they collect and publish a large volume of internet

traffic from as many countries around the world as possible (including, of

course, the country where an internet blackout has been reported), or that they

provide insight into the routing within networks.

Some public data sources, such as Google Transparency Reports,

provide data with large volumes of internet traffic because they are produced by

companies offering internet services used by large populations across many

countries around the world. Other data sources, such as NDT measurements, publish data collected

from probes monitoring network performance globally. And other data sources,

like Tor Metrics, publish daily measurements

from around the world pertaining to the use of particular software.

Data sources that provide insight into the potential routing within networks can

also be useful when examining internet blackouts. BGP data aggregated by

RIPE, for example, enables us to monitor routing

information for the country in question and to examine whether it has been

disconnected from the internet.

In short, some public data sources that we refer to when examining internet

blackouts include the following:

The above list is not exhaustive and the listed data sources present various

limitations. NDT measurement data,

for example, is limited by the amount of probes deployed which may not include

equal coverage across countries around the world, while Google traffic data is

limited by the amount of users Google has in each country of question. Such data

sources, however, can potentially help gain insight into the volume of internet

traffic originating from various countries around the world through further

examination.

Examining data sources

Most public data sources (as listed in the previous section) allow us to select

a country and to observe the flow of internet traffic originating from it across

time. If a country-wide internet blackout has occurred, we would expect to see

almost no internet traffic origination from a country during the reported period

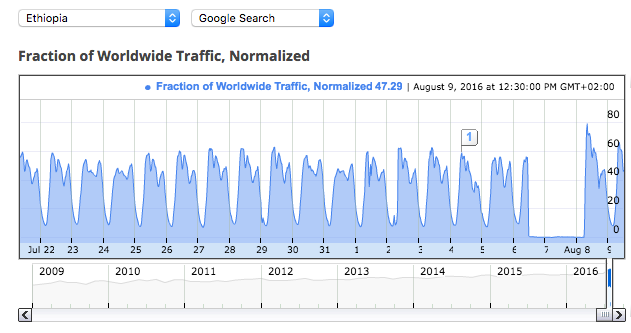

of a blackout. This, for example, was evident in Ethiopia in August 2016, when

an internet blackout was reported in the middle of political protests.

The graph below, taken from Google traffic data,

clearly illustrates that no internet traffic was originating from Ethiopia

between 6th to 8th August, confirming that an internet blackout occurred.

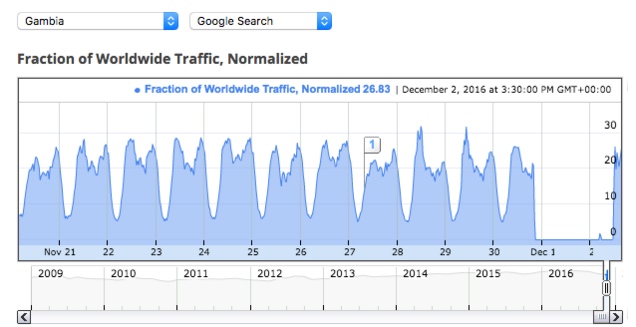

Similarly, Google traffic data in the graph

below shows a clear disruption of internet traffic originating from the Gambia

between 30th November to 2nd December, when an internet blackout was

reported during

the country’s 2016 presidential election.

In addition to Google traffic data, it’s also particularly useful to look at BGP

announcement data aggregated by RIPE from different Remote Route Collectors (RRT) and to examine whether

a country’s prefixes are withdrawn when an internet blackout is being reported.

In the Gambia, for example, such data allowed us to monitor the withdrawal and

announcement of Gambian prefixes during the country’s 2016 presidential

election. In fact, Gambian prefixes were

withdrawn between

30th November to 2nd December, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the

internet blackout occurred during that period, as inferred through Google traffic data.

OONI has been working on a methodology to automatically identify and

investigate cases of internet blackouts. So for this is something very

experimental and will require more work to have it be production ready.

This ipython notebook (view)

contains some of the results of the experiments we have been doing.

The same methodology can easily be applied to other datasets other than the

Google traffic data. It would have been useful, and much easier, if Google

Transparency Reports provided an easy to use HTTP API for obtaining the data.

Cross-referencing data sources

Internet blackout might not always occur across all networks on a country-wide

level. A government, for example, may order ISPs to shut down the internet only

in a specific location where a protest is taking place, while keeping the

internet accessible in the rest of the country. In such a case, it’s probably

unlikely that Google traffic data would show a complete disruption as

illustrated in the graphs of the previous section, but would rather show a

general decrease in traffic data in comparison to previous dates. As such,

cross-referencing data sources as part of an examination of internet blackout

can be a useful next step.

One way of doing so is by looking at both Google traffic data and

Tor Metrics for a particular country during

the same period of time. It’s unlikely, for example, that there would be a total

internet blackout if there is normal usage of the Tor network during a reported blackout. If, however,

there is a spike in Tor usage and Google traffic data is significantly decreased

in comparison to previous dates, then it might be the case that censorship

events are occurring in certain networks, leading to the increased usage of

censorship circumvention software.

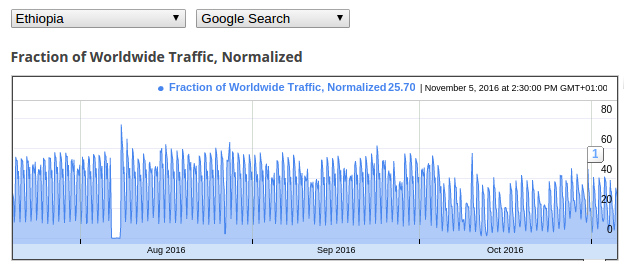

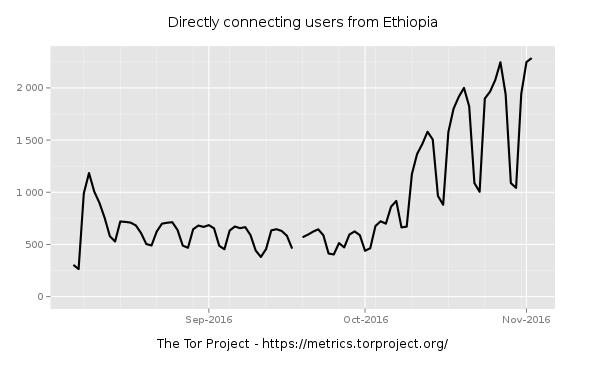

This is illustrated through the example below where we can see decreased Google

traffic data and increased usage of Tor software in Ethiopia

in October 2016.

When cross-referencing data sources, it might also be useful to look at the

geotagging of posts on social media platforms, such as Twitter. Unlike the

aforementioned public data sources (e.g. Google transparency reports) which show

an overview of traffic originating from a country, the geotags on posts allow us

to drill down to a specific region or city in a country (if the geotags are

accurate). This is particularly useful if, for example, locals are reporting a

blackout in a country, Google traffic data does not show a clear blackout, but

you’re interested in examining whether the approximate internet activity

originating from a specific city or region has been disrupted.

This process involves:

Collecting all of the posts of a social media platform (e.g. via Twitter’s API)

that are geotagged with the region that you are interested in;

Calculating the approximate amount of geotagged posts within the time range that

you are interested in;

Evaluating whether there is a significant decrease of geotagged posts on the

specific dates of a reported internet blackout.

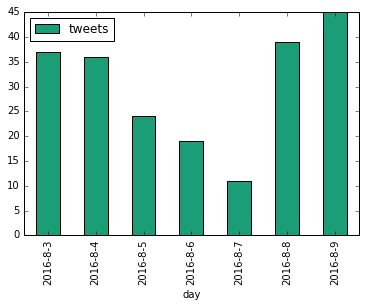

This is illustrated through the graph below that we

created based on tweets geotagged in Ethiopia between 3rd-9th August

2016, indicating a decrease of Twitter activity in the country on 7th August

2016 when an internet blackout was reported in the country.

However, such data should probably only be used supplementary when cross-

referencing data sources, since it is subject to various limitations (for

example, Twitter users in a country might be inactive due to reasons unrelated

to an internet blackout).

Conclusion

Unless all data sources that you refer to show absolutely no internet traffic

originating from a country or the prefixes within a country are completely

withdrawn, it’s hard to reach an accurate conclusion on whether an internet

blackout has occurred or not.

Nonetheless, the publicly available data sources mentioned in this post can help

gain some insight into the flow of internet traffic in most countries around the

world, and they can help provide signs of internet blackout.

We encourage more companies (such as Akamai,

CloudFlare and Fastly)

to publish data on network traffic originating from countries to help increase

transparency when heavy network disruptions occur. We also encourage you all to

support Access Now’s #KeepItOn campaign

for a stable and open internet around the world.