Uganda: Data on internet blocks and nationwide internet outage amid 2021 general election

Maria Xynou (OONI), Simone Basso (OONI), Ramakrishna Padmanabhan (CAIDA, UC San Diego), Arturo Filastò (OONI), DefendDefenders, Defenders Protection Initiative

2021-01-22

Last week, amid its 2021 general election, Uganda was

disconnected

from the internet entirely. The country experienced a widespread internet blackout that lasted 4 days,

starting on the eve of the election (13th January 2021) and ending in

the morning of 18th January 2021. In the days leading up to the

election, access to major social media platforms and circumvention tools

was blocked

– even when the OTT (Over the Top) tax (commonly referred to as

the “Social Media Tax”) was paid.

In this report, we share OONI network measurement data

on the blocking of social media and circumvention platforms leading up

to Uganda’s elections, as well as IODA data

(and other public data sources) on the internet blackout that occurred

amid and following the election. We also share findings from experiments

run in Uganda (before and after the internet blackout) through the use

of the miniooni research client.

Background

Uganda has had the same President (Mr. Yoweri Museveni) since 1986.

Multiparty elections have been

held in the country

since 2006, but President Museveni (and his National Resistance Movement party) has won every election over the last

35 years (even though past elections have been marred by allegations of rigging).

During Uganda’s 2016 general election, access to

major social media platforms was

blocked both

amid the election (in February 2016) and leading up to President

Museveni’s (fifth) inauguration (in May 2016). At the time, authorities

justified the

blocking of social media on the grounds of security, though this

reportedly

harmed the political opposition which relied on social media platforms

to organize protests.

Two years later (in July 2018), Uganda

introduced

the Over the Top (OTT) tax – commonly referred to as the “Social Media Tax” – which

requires internet users in Uganda to pay taxes to the government in

order to access a wide range of online social media platforms (such as WhatsApp,

Facebook, Twitter, Viber, Google Hangouts, Snapchat, Skype, and

Instagram, among many others). To access such platforms, users of

Ugandan Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are required to pay UGX 200 (USD 0.05) per day, which has

reportedly

led to millions of people in Uganda abandoning online social media due

to affordability constraints.

According to President Museveni, this social media tax is

meant

to reduce capital flight and improve Uganda’s tax to GDP ratio. However,

previous studies in the region have

shown that restricting internet access (through internet disruptions)

and increasing the cost of internet access have the potential to impact

Uganda’s economic growth.

To limit untaxed access to social media, Ugandan ISPs have also

blocked

access to a number of circumvention tools as well. In 2018, we published

a research report

which documented the blocking of online social media and censorship

circumvention platforms in Uganda (when the OTT tax was not paid)

through the analysis of OONI network measurement data.

Over the last 2.5 years, people in Uganda had access to major social

media platforms if they paid the OTT tax. But this changed in the

week leading up to Uganda’s latest (2021) general election (held on 14th

January 2021), when Ugandans

reported

that they were unable to download apps from the Google Play Store. In

the days that followed, locals also

reported

that they were unable to access major social media platforms (such as

Facebook) – even once they had paid the OTT tax.

On 12th January 2021, Ugandan ISPs

confirmed the

blocking of online social media platforms and online messaging

applications in compliance with a directive from the UCC.

The recent blocking of social media reportedly followed Facebook’s closure of “fake” accounts which it said

were linked to Uganda’s government and used to boost the popularity of

posts. This move was seen as a form of retaliation as (on

12th January 2021) President Museveni accused Facebook of “arrogance”

for determining which accounts are fake and interfering with the

election; he stated that he had therefore instructed the blocking of

Facebook and other social media platforms. To limit censorship

circumvention, the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC)

reportedly

ordered the blocking of more than 100 VPNs.

On the eve of Uganda’s 2021 general election, the UCC

ordered the suspension of the operation of all internet gateways and

associated access points in Uganda. The order specified that this

suspension should take effect at 7pm on 13th January 2021, as

illustrated below.

Overall, the run-up to Uganda’s 2021 general election was marred by

violence, as authorities

reportedly

cracked down on opposition rallies, while opposition candidates and

their supporters experienced threats and intimidation over the last

months. President Museveni’s re-election was primarily challenged by

Bobi Wine

(one of 10 candidates challenging President Museveni in the 2021 general

election), a 38-year-old pop star who emerged as a prominent member of

Uganda’s political opposition in 2017 and ran for Uganda’s presidency in

the latest election. However, Mr. Museveni was

re-elected, winning

almost 59% of the vote and a sixth presidential term (despite

accusations of vote fraud by the opposition).

Methods

To investigate the blocking of online platforms, we analyzed OONI measurements collected from Uganda

(similarly to our 2018 study examining the

blocking of social media and circumvention tools with the introduction

of the OTT tax). OONI measurements are regularly collected and

contributed by users of the OONI Probe app, which is free and open source, designed to

measure various forms of internet

censorship and network interference.

More specifically, we limited our analysis to OONI measurements

collected from Uganda between 9th January 2021 to 19th January 2021,

as network disruptions were first

reported on

9th January 2021, while internet connectivity was

restored

in the country by 18th January 2021. We further limited our analysis to

OONI measurements pertaining to the testing of social media websites and

apps, as well as to the testing of circumvention tool websites and apps.

While a wide range of social media and circumvention tool websites can

be tested through OONI’s Web Connectivity test (designed to measure

the TCP/IP, DNS, and HTTP blocking of websites), the OONI Probe app currently only includes tests for the

following social media apps:

WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and

Telegram. Quite similarly, the

OONI Probe app currently only includes tests for the following

circumvention tools: Tor and

Psiphon. Our analysis was

therefore limited to the testing of these specific apps.

Our findings are also limited by the type and volume of measurements

contributed by volunteer OONI Probe users in Uganda (i.e. if a blocked

service was not tested in Uganda in the analysis period, relevant

measurement findings will not be available). Prior to 12th January 2021,

there was a divergence of

measurements

from probes run by users who had and had not paid the OTT tax. After 12th January 2021,

we observed the disappearance of that divergence as users who had paid

OTT tax experienced the blocks previously instituted on ones who had not

paid the tax, as well as new blockages imposed on all users.

To investigate the blocking of circumvention tools further, we also ran

a series of experiments (with the help of volunteers in Uganda) through

the miniooni research client. We ran these experiments to

characterize TLS blocking patterns. As test cases, we selected the Play

Store’s website, ProtonVPN’s website, and Facebook’s website. We checked

whether their blocking depended on DNS, TCP, or TLS blocking. In the

case of TLS blocking, we further investigated whether it depended on the

value of the SNI extension.

To explore Uganda’s internet blackout (when access to the internet was

disrupted entirely), we referred to the following public data sources:

Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA),

Google traffic data,

Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map,

and Cloudflare Radar data.

Our goal was to check whether the signals and timing of Uganda’s

internet blackout can be verified and corroborated by all four separate

public data sources, and how they can compare to the UCC order (which

instructed

the suspension of internet gateways and associated access points at 7pm

on 13th January 2021).

Blocks in the election run-up

App Stores

On 9th January 2021, people in Uganda started reporting

that they experienced difficulties downloading apps from the Google Play

Store. This appears to be corroborated by OONI measurements,

which show that the testing of google.play.com presented signs of blocking

on several networks almost every time that it was tested between 10th

January 2021 to 18th January 2021 (the relevant URL was not tested in

Uganda on 9th January 2021).

While we also heard reports of potential Apple App Store blocking too,

we cannot confirm this based on OONI measurements, which show that

apps.apple.com was

accessible

on several networks in Uganda every time it was tested between 11th

January 2021 to 18th January 2021. It is possible though that it may

have been blocked on different networks (in comparison to those tested),

or that access may have been interfered with in ways beyond those

measured.

Websites

In the days leading up to Uganda’s 2021 general election, OONI

measurements show that a number of social media websites presented signs of blocking.

These include www.facebook.com, the

blocking

of which appears to have started on 12th January 2021 (following

President Museveni’s instruction to restrict Facebook access

in response to Facebook’s closure of “fake” accounts, and on the same

day that Ugandan ISPs

notified

their customers of such blocking) and which appears to be ongoing. Most

OONI measurements

collected between 12th January 2021 to 19th January 2021 suggest the

blocking of www.facebook.com on several networks in Uganda.

Similarly, OONI measurements collected from Uganda on the testing of

www.instagram.com between 12th January 2021 to 19th January 2021

suggest the ongoing blocking

of this social media website (though a relatively limited volume of

measurements – in comparison to the testing of www.facebook.com –

has been collected during this period). While the testing of

www.whatsapp.com first presented signs of blocking

on 9th January 2021, we more consistently observed signs of blocking

between 12th January 2021 to 19th January 2021.

All OONI measurements collected between 12th January 2021 to 19th

January 2021 consistently show that access to twitter.com appears to

have been

blocked

on several networks in Uganda. Similarly, all OONI measurements

collected during this time frame on the testing of www.viber.com

show that access to this website was

blocked

in Uganda as well. During this period, we also observed signs of blocking

for many other social media websites, such as

skype.com,

snapchat.com,

wechat.com,

tumblr.com,

linkedin.com,

as well as the blocking of dating sites (such as

grindr.com).

Interestingly, www.youtube.com (which is not included amongst the OTT taxed platforms) only

started presenting signs of blocking from 18th January 2021

onwards, once internet connectivity in Uganda was restored (following

the 4-day internet blackout). This is not only shown through relevant

OONI measurements

collected from multiple networks in Uganda, but YouTube disruption is

also suggested through Google traffic data

which shows that the levels of YouTube traffic originating from Uganda

are significantly decreased in comparison to the pre-internet blackout

levels, as illustrated below.

Source: Google Transparency Reports, Traffic and disruptions to

Google: YouTube, Uganda,

https://transparencyreport.google.com/traffic/overview?fraction_traffic=start:1608422400000;product:21;region:UG&lu=fraction_traffic

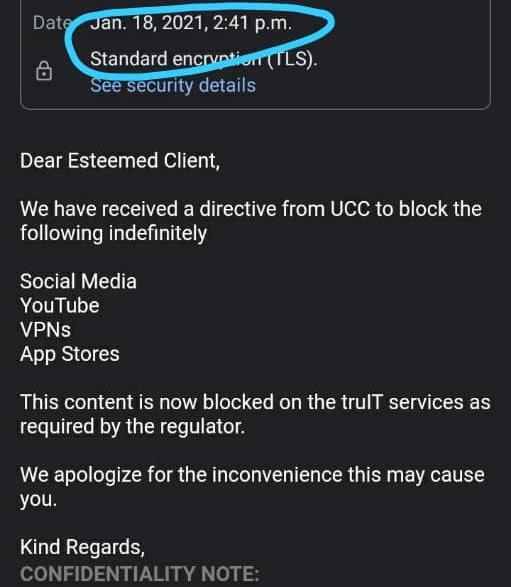

This is further corroborated by a notification that Ugandan internet

users received from their ISPs on 18th January 2021, which explicitly

lists YouTube among the blocked internet services (in compliance with a

UCC directive).

It is possible that this move may be in response to government orders to

censor specific YouTube channels affiliated with the political

opposition. Following deadly riots in November 2019 over the arrest of

opposition presidential candidate (Bobi Wine), it was

reported

in December 2019 that the UCC wrote to Google requesting that over 14

YouTube channels be shut down for allegedly mobiling the riots. The UCC

claimed

that these YouTube channels spread misinformation, fueled riots, and

undermined public interest. Possibly as a result of non-compliance on

Google’s end, the Ugandan government may have resorted to blocking

YouTube itself. Given that YouTube is hosted on encrypted HTTPS, ISPs

cannot limit the blocking to specific channels, but rather need to block

the whole of www.youtube.com.

It’s worth noting that in all the above social media cases, we observe

the same HTTP failures

and connection reset errors in OONI measurements, increasing our

confidence with respect to their blocking because ISPs often block

websites through the use of the same techniques. This is also consistent

with our measurement findings in our 2018 study in Uganda. The

following sections (“Characterizing website blocking”) dive into this

deeper, as we investigated some of the blocked websites through the use

of more advanced techniques (which we haven’t integrated into the OONI Probe apps yet).

Apps

To examine the blocking of social media apps, we analyzed OONI data

collected from Uganda on the testing of

WhatsApp,

Facebook Messenger,

and

Telegram.

Starting from 12th January 2021, all three apps presented signs of

blocking on several networks, as illustrated through the chart below.

Source: OONI measurements collected from Uganda between 9th January

2021 to 19th January 2021,

https://explorer.ooni.org/search?until=2021-01-20&since=2021-01-09&probe_cc=UG

Through the above chart, it is evident that:

All three apps (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Telegram) presented

signs of blocking on several Ugandan networks (including major

providers, such as MTN) on 12th and 13th January 2021;

These apps did not present signs of blocking on all networks, as

some tests suggested that the apps worked on some networks

(between 12th and 13th January 2021);

No OONI measurements were collected from Uganda between 14th January

2021 to 17th January 2021, suggesting the presence of an internet

outage (since OONI Probe requires internet connectivity to perform

tests, and the absence of measurements is consistent across all

networks in Uganda during this time frame);

OONI Probe testing (across networks) in Uganda resumes at around the

same time on 18th January 2021, further suggesting the presence of

an internet outage during the previous days;

Social media apps remain blocked (the blocking of which is suggested

by a larger volume of measurements in comparison to previous days)

from 18th January 2021 onwards on most networks.

More specifically, WhatsApp appears to be blocked

because attempted connections to WhatsApp’s registration service and web

interface (web.whatsapp.com) consistently

fail.

While DNS lookups consistently resolve to IP addresses associated with

Facebook, Facebook Messenger appears to be blocked

because attempted TCP connections to Facebook’s endpoints

failed.

In many Telegram measurements,

we see that TCP connections to some Telegram endpoints succeed, while

others

fail,

and that HTTP(S) GET requests to web.telegram.org do not send back a

consistent response to OONI servers. As these patterns (for WhatsApp,

Facebook Messenger, and Telegram) are quite consistent across many

measurements and networks throughout the same time periods, they provide

strong signals of potential blocking.

To limit censorship circumvention, the Uganda Communications Commission

(UCC)

reportedly

ordered the blocking of more than 100 VPNs in the days leading up to the

country’s 2021 general election.

As the OONI Probe app currently only includes 2 circumvention tool

tests, we can only share relevant measurements for those 2 tools:

Tor and

Psiphon. In both cases, we did

not observe any significant signs of blocking, as most measurements

(collected from multiple networks in Uganda) showed that the tools

worked as expected. This is illustrated through the following chart,

which shares OONI measurement coverage per test across networks (showing

that almost all test results indicated that

Tor and

Psiphon worked).

Source: OONI measurements collected from Uganda between 9th January

2021 to 19th January 2021,

https://explorer.ooni.org/search?until=2021-01-20&since=2021-01-09&probe_cc=UG

As is evident through the above chart, Psiphon appeared to work

on multiple networks in Uganda between 9th January 2021 to 19th January

2021 (excluding the days between 14th to 17th January 2021, when there

appears to have been an internet outage). Throughout this period, the

OONI Probe Psiphon test was able

to successfully bootstrap and create the Psiphon tunnel, and use it to

fetch a webpage from the internet (suggesting that this circumvention

tool worked in the tested networks).

Psiphon accessibility in Uganda is further suggested by the Psiphon Data Engine,

which shows the number of Psiphon connections originating from Uganda.

Source: Psiphon Data Engine, Connections from Uganda (January 2021),

https://psix.ca/d/nyi8gE6Zk/regional-overview?orgId=2&var-region=UG

The above graph (taken from the Psiphon Data Engine)

shows an increase in connecting Psiphon users between 11th to 13th

January 2021 (which is when Ugandan ISPs were

instructed to

start blocking social media platforms, regardless of OTT tax payment), possibly in an

attempt to circumvent social media censorship. Starting from the evening

of 13th January 2021 (which is when the UCC instructed the suspension of

all internet gateways), we observe a complete drop in Psiphon users

(lasting for several days), and we see that Psiphon users resume

connections by 18th January 2021 (which coincides with the dates of the

reported internet blackout).

However, starting from 18th January 2021, the OONI Probe Psiphon test started to present signs of potential Psiphon blocking on Airtel (AS37075);

while the test was able to bootstrap Psiphon, it was unable to fetch a webpage

from the internet. These findings though are not conclusive, since very

few Psiphon measurements have been collected from Airtel (AS37075) since

18th January 2021. We therefore encourage further Psiphon testing on

this network.

Similarly to Psiphon, Tor appeared to work

on multiple networks in Uganda between 9th January 2021 to 19th January

2021 (excluding the days between 14th to 17th January 2021, when there

appears to have been an internet outage). As part of OONI Probe Tor testing throughout this period, most

reachability measurements of selected Tor directory authorities and

bridges were successful. Even in the cases where OONI measurements

presented a few anomalies, Tor still appeared to be functional given

that some Tor directory authorities were reachable.

Tor accessibility in Uganda is further suggested by Tor Metrics,

which shows the estimated number of directly connecting Tor users from

Uganda.

Source: Tor Metrics, Directly connecting users from Uganda (January

2021),

https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-relay-country.html?start=2021-01-09&end=2021-01-20&country=ug&events=off

The above graph (taken from Tor Metrics)

shows that there was a spike in Tor usage on 12th January 2021 (which is

when Ugandan ISPs were

instructed to

start blocking social media platforms, regardless of OTT tax payment), possibly in an

attempt to circumvent social media censorship. Starting from the evening

of 13th January 2021 (which is when the UCC instructed the suspension of

all internet gateways), we observe an almost complete drop in Tor users,

which coincides with the dates of the reported internet blackout.

As internet connectivity resumed in Uganda, so did the number of Tor

users in Uganda.

Apart from the testing of tools, OONI measurements also suggest the

potential blocking of several circumvention tool websites

which presented the same type of anomalies (with connection_reset

errors) during the analysis period. These include

protonvpn.com,

safervpn.com,

hotspotshield.com,

nordvpn.com,

torproject.org,

and

ultrasurf.us.

However, the blocking of such websites does not necessarily mean that

their apps are blocked as well (this, for example, does not appear to be

the case with Tor, which seems to

work

in Uganda).

On 22nd January 2021, it was reported that the Ugandan government is threatening to arrest VPN users, and that they plan to block all websites offering VPN services.

Characterizing website blocking

We ran custom experiments

with miniooni to determine the extent of the blocking. This client

allows us to test experimental measurement methodologies that have not

been integrated into the regular OONI tests yet.

We ran tests with and without TLSv1.3, changing the SNI or the target

endpoint and using QUIC/HTTP3 instead of HTTP. In the following

sections, we only discuss tests measuring the Play Store’s website,

ProtonVPN’s website, and Facebook’s website.

Play Store’s website

We tested https://play.google.com eight times on MTN on 19th and

20th January 2021 (once internet connectivity had been restored in

Uganda). All domain name resolutions succeeded. They all returned IP

addresses belonging to Google’s autonomous system (AS15169). We

therefore excluded the possibility of DNS interference.

Figure: Play Store measurements from MTN

All TLS handshakes using TLSv1.3 and play.google.com as the SNI

failed. In seven cases

(#1,

#2,

#3,

#4,

#5,

#6,

#7),

the error was connection reset (ECONNRESET). This error forces the

operating system kernel to close a TCP connection immediately. In the remaining case,

the error was “network down” (ENETDOWN). This error indicates that a

router could not forward our traffic through a dead network.

If we inspect the ENETDOWN

measurement,

we see the error happening right after sending the TLS ClientHello

message. (The failure is the seventh event in the network_events

key inside the test_keys key.) The time elapsed between sending the

ClientHello and receiving the ENETDOWN error is comparable to the

round trip time (100 ms). (We estimate the round trip time by observing

the time required for the connect system call to complete.)

One of the measurements that failed with ECONNRESET was from a SIM

card where the OTT tax hadn’t been paid. All other failures were from

SIM cards with the OTT tax paid.

After every measurement, we ran another measurement using

example.com as the SNI. Eight times out of eight, we received the

ServerHello (see, e.g.,

#1,

#2,

and

#3).

This result strongly indicates SNI based blocking of the Play Store’s

website.

ProtonVPN’s website

We tested https://protonvpn.com fourteen times from MTN and fourteen

times from Airtel. We ran these measurements between 13th to 20th

January 2021.

In both networks, we saw no DNS errors. The domain name resolutions

always returned IP addresses belonging to the Proton VPN autonomous

system (AS209103). We therefore excluded the possibility of DNS

interference.

MTN

Measurements always failed when using the protonvpn.com SNI on MTI

and TLSv1.3. The failure was ECONNRESET nine times (see, for

example,

#1,

#2,

and

#3).

We observed three ENETDOWN errors

(#1,

#2,

and

#3).

In two cases, the experiment failed because of an error in our

measurement script.

Figure: ProtonVPN measurements from MTN

One of the ECONNRESET failures was from a SIM without the OTT tax

paid. All these failures occurred while the TLS handshake was in

progress.

The ENETDOWN errors occurred roughly 50 ms after sending the

ClientHello. In all these cases, the connect time was at least 200 ms.

After every measurement, we ran another one with example.com as the

SNI and TLSv1.3. In all fourteen cases, we successfully received the

ServerHello (see, e.g.,

#1,

#2).

This result strongly suggests SNI based blocking.

Airtel

All nine measurements run before 20th January 2021 succeeded. After that

date, we observed three ENETDOWN errors

(#1,

#2,

#3)

and two timeout errors

(#1,

#2).

All these errors occurred when connecting.

Figure: ProtonVPN measurements from Airtel

We also tried connecting to https://example.com using TLSv.13 and

protonvpn.com as the SNI after each regular measurement. Fourteen

times out of fourteen, we received the ServerHello (see, for example,

#1,

#2).

This result indicates that there was no SNI based blocking. Consistent

failures after 20th January 2021 suggest that there was TCP blocking.

Facebook’s website

We tested https://facebook.com and https://www.facebook.com

between 18th and 20th January 2021 from MTN and Airtel. All domain name

resolutions returned IP addresses belonging to Facebooks’ autonomous

system (AS32934). We therefore excluded the possibility of DNS

interference with the measurements.

We measured https://facebook.com and https://www.facebook.com

nineteen times from MTN and fourteen times from Airtel.

MTN

We always failed to connect to both domains. The error was “connection

refused” nine times for each domain (e.g.,

#1,

#2)

and ENETDOWN once for each domain (e.g.,

#1,

#2).

Figure: Facebook measurements from MTN

To search for SNI blocking evidence, we repeated each measurement after

a short time interval using TLSv1.3 and the same SNIs with

https://example.com. We observed failures connecting (three times

out of nine for each SNI; see, for example,

#1)

and during the TLS handshake (six times; e.g.,

#1).

We conclude that there was evidence of SNI based blocking for both

facebook.com and www.facebook.com. We also note that

https://example.com has not always been reliably reachable during

the testing period.

Interestingly, we could not access Facebook’s website using the QUIC

protocol (h3-29). The QUIC handshake always timed out (see, e.g.,

#1,

#2,

#3).

By inspecting the network_events key of these measurements, we

notice that the code calls sendto several times (sendto is

called write_to in network_events). Each time, it writes the

initial message containing the ClientHello. Because there is no reply,

the message is transmitted several times. Eventually, the client times

out.

We repeated each experiment using example.com as the SNI (see, e.g.,

#1

and

#2).

The behavior of the QUIC client is the same as before. It calls

sendto several times, and then eventually it times out. We conclude

that these Facebook QUIC endpoints are likely blocked.

Airtel

We recorded nine failures and four successes. The successes all occurred

around the morning of 19th January 2021. In all cases, we failed when

connecting (see, e.g.,

#1,

#2,

#3).

This result indicates that there is blocking of the relevant TCP

endpoints.

Figure: Facebook measurements from Airtel (using TCP)

We nearly immediately repeated the experiment using TSLv1.3 and the same

SNIs with https://example.com. All these experiments failed in the

TLS handshake. In five out of thirteen cases, the error was ENETDOWN

(see, e.g.,

#1).

In all other cases, the error was ECONNRESET (see, e.g.,

#1).

This result indicates that there is SNI based blocking, in addition to

TCP blocking.

As for MTN, Facebook’s QUIC endpoints failed

(#1,

#2,

#3,

#4,

#5,

#6,

#7,

#8,

#9).

All these measurements failed after the QUIC handshake completed. The

client and the server exchange some extra data after the handshake, then

the client times out reading or writing. When it times out writing, it

retransmits several times before giving up. When it times out reading,

it just blocks until there is no network activity for several seconds.

Figure: Facebook measurements from Airtel (using QUIC)

We retried using example.com as the SNI. The QUIC handshake, of

course, completed successfully (see, e.g.,

#1,

#2,

#3).

There was no reason to expect otherwise. The QUIC handshake succeeded

for facebook.com and www.facebook.com as well. We cannot say

whether the failures were in some way related to using Facebook SNIs in

the QUIC handshake.

It remains nonetheless curious that we had observed QUIC failures when

using Facebook QUIC endpoints at the same time when the TCP endpoints

were failing.

Internet outage amid 2021 general election

On the eve of Uganda’s 2021 general election (in the evening of 13th

January 2021), the country was disconnected from the internet entirely.

Uganda remained disconnected from the internet on election day (14th

January 2021), and the nationwide internet outage lasted for almost 5

days (as internet connectivity was restored in the morning of 18th

January 2021). This internet outage is visible through several public

data sources: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA),

Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map,

Cloudflare Radar, and

Google traffic

data.

The Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) project of the Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) measures

Internet blackouts worldwide in near real-time. To track and identify

internet outages, IODA uses three complementary measurement and inference methods: Routing (BGP)

announcements, Active Probing, and Internet Background Radiation (IBR)

traffic. Access to IODA measurements is openly available through their

Dashboard, which enables

users to explore internet outages with county, region, and AS level of

granularity.

IODA data

from the following chart (taken from the IODA dashboard) clearly shows that

Uganda experienced a widespread internet outage, starting at around

16:00 UTC on 13th January 2021 (which is 19:00 in Uganda, the same time

that the UCC instructed the suspension of all internet gateways), and

lasting up until around 09:30 UTC on 18th January 2021.

Source: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), IODA Signals

for Uganda,

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=country/UG&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

Within this time period, we observe a major drop in both active probing

and IBR signals, and also a drop in the BGP signal correlating in time

with the drop in the other signals, strongly suggesting that Uganda

experienced a widespread internet outage. This is further indicated by

the fact that we see these signals resume to their previous levels on

18th January 2021.

Quite similarly, Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map tracks internet disruptions

worldwide based on three signals: Traceroute completion ratio, BGP

routes, and DNS query rate. Between 13th to 18th January 2021, Oracle’s

Internet Intelligence Map records the same internet outage

in Uganda as IODA data

(with almost identical timings in the drop of signals).

Source: Oracle Internet Intelligence Map, Uganda (January 2021),

https://map.internetintel.oracle.com/?root=national&country=UG

This internet outage is further corroborated by Cloudflare Radar data, which

tracks internet traffic disruptions worldwide. The following graph

clearly shows that almost no internet traffic originated from Uganda

between (the evening of) 13th January 2021 to (the morning of) 18th

January 2021 – similarly to both

IODA

and Oracle Internet Intelligence

data.

Source: Cloudflare Radar, Change in Internet Traffic in Uganda

(January 2021),

https://radar.cloudflare.com/ug?date_filter=last_30_days

Uganda’s internet outage is further corroborated by Google traffic data,

which very visibly shows that almost no Google traffic originated from

Uganda during the same time period. It also shows that Google traffic

resumed on 18th January 2021, similarly to what is shown by

IODA,

Oracle Internet Intelligence,

and Cloudflare Radar data.

Source: Google Transparency Report, Traffic and disruptions to

Google: Uganda (January 2021),

https://transparencyreport.google.com/traffic/overview?hl=en&fraction_traffic=start:1609459200000;end:1611187199999;product:19;region:UG&lu=fraction_traffic

As the same internet outage (involving the same dates and times) is

shown through four separate data sources, we are confident that Uganda

experienced a severe internet outage amid its 2021 general election.

This is further suggested by the absence of OONI measurements from Uganda

during this time period (since OONI Probe

requires internet connectivity to perform tests), as well as by the

drastic drop in Tor users

and Psiphon users

during this period.

When asked about this internet outage, Mark Kiggundu, Technology Program

Manager of DefendDefenders, said:

“The internet as a vast network of people, information and knowledge

enable individuals to enjoy diverse human rights including the right to

freedom of opinion and expression. It is also a source of livelihood for

many and a major contributor to development in any given state.

Therefore, interference with its access or availability not only

infringes on fundamental human rights, but is also a threat to life and

livelihood.”

Network-level analysis

IODA provides data at the network-level granularity,

allowing us to drill-in deeper and examine which networks were affected

by the internet outage in Uganda. Analyzing network-level data also

allows us to examine if there were differences in the times at which the

outage began and ended across various networks.

Unlike previous large-scale government-mandated blackouts (such as the Iranian nation-wide blackout in 2019) where there

were significant differences in outage times across networks, many

networks in Uganda appear to have experienced outages that began and

ended at the same time.

Source: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), Active

probing signals for networks whose outages began and ended at the same

time.

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/36997&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/327687&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37063&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37122&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37113&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

The above graph shows IODA’s active probing signal for five major

networks in Uganda; we see that the outage began at around 16:00 UTC on

13th January 2021 and ended at around 09:30 UTC on 18th January 2021 for

all these networks. This level of coordination in timings suggests that

network operators were able to anticipate and execute the enforcement

and the relaxation of the shutdown according to pre-planned schedules.

Although the timing patterns of the outages are identical across the

networks below, the way these outages manifest in IODA’s signals varies.

Source: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), BGP signals

for networks whose outages began and ended at the same time. Only some

of these networks’ outages are visible in BGP.

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/36997&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/327687&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37063&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37122&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37113&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

The graph above shows IODA’s BGP signals for the five networks from the

previous graph that had similar outage timing patterns. We see that only

some of these networks’ outages are visible in the BGP signal although

each had a noticeable drop in the active probing signal. There is a

large drop in BGP-visible /24 blocks for RENU (AS327687) and Tangerine

(AS37113) and a smaller but discernible drop for Smile (AS37122).

However, Infocom (AS36997) and Roke (AS37063) do not see any drop in

BGP-visible /24 blocks during this period. These dissimilarities in the

outage’s signature in IODA’s signals may reflect the use of different

approaches by these networks’ operators for disconnecting their

networks.

Source: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), Active

probing signals for networks whose outages began before/after 16:00 UTC

on 13th January 2021 (the time at which most other networks’ outages

began).

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/36991&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/20294&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/21491&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

Not all networks experienced the outage at the same time, however. The

outage affecting Africell Uganda (AS36991) began several hours earlier,

at around 13:00 UTC on 13th January 2021. On the other hand, the outage

affecting MTN (AS20294) and Uganda Telecom (AS21491) began a few hours

later, at around 19:00 UTC. Like the dissimilarities in outage

signatures across networks, these differences in timing patterns also

suggest that the implementation of the shutdown was left to the network

operators.

Source: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), Active

probing signals for networks that experienced short but significant

outages before 13th January 2021.

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/29039&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/36977&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

https://ioda.caida.org/ioda/dashboard#view=inspect&entity=asn/37075&lastView=overview&from=1610280000&until=1611057600

Some networks appeared to experience brief but major outages even before

the multi-day outage that began on 13th January 2021. Two ASNs operated

by Airtel Uganda (AS36977 and AS37075) experienced a brief outage on

12th January 2021 at around 00:30 AM UTC and another short outage on

12th January 2021 at around 09:00 AM UTC. Africa Online Uganda (AS29039)

experienced an outage on 12th January 2021 at around 22:00. These

outages could perhaps be due to potential tests that network operators

may have performed in anticipation of the government order to suspend

internet connectivity.

Conclusion

During Uganda’s last general election (in 2016), access to major social

media platforms was

blocked. Now,

amid its 2021 general election, Uganda not only experienced social media

blocking (regardless of OTT tax payment), but also a

4-day internet outage.

In the days leading up to Uganda’s 2021 general election, ISPs appear to

have blocked access to the Google Play Store

(hampering people’s ability to download apps), as well as to a number of

social media apps (including

WhatsApp,

Facebook Messenger,

and

Telegram)

and websites (such as

facebook.com)

– regardless of OTT tax

payment. Access to certain circumvention tool websites (such as

protonvpn.com)

appears to have been blocked as well, though both

Tor

and

Psiphon

appear to have worked throughout the election period.

Starting from the eve of Uganda’s 2021 general election (in the evening

of 13th January 2021), Uganda was disconnected from the internet

entirely. The country experienced a 4-day internet outage (which

included election day), as shown through several public data sources:

Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA),

Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map,

Cloudflare Radar, and

Google traffic

data. This is further corroborated by the absence of OONI measurements from Uganda

during this time period (since OONI Probe

requires internet connectivity to perform tests), as well as by the

drastic drop in Tor users

and Psiphon users

during this period.

Even though internet connectivity in Uganda was

restored

on 18th January 2021, access to social media and circumvention platforms

remained blocked. Notably, Ugandan ISPs only appear to have started blocking access to YouTube on 18th January 2021,

even though the platform is not included on the OTT list of taxed platforms.

While Ugandan ISPs (such as

MTN) have

been transparent to their customers about these internet restrictions,

the necessity and proportionality of these restrictions remain quite

unclear, particularly since they coincided with the electoral process

when access to information and communications platforms is crucial.

Acknowledgements

We thank OONI Probe users in Uganda who

contributed measurements, making this study possible.