Iran’s nation-wide Internet blackout: Measurement data and technical observations

Ramakrishna Padmanabhan (CAIDA, UC San Diego), Alberto Dainotti (CAIDA, UC San Diego), Nima Fatemi (Kandoo), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Maria Xynou (OONI), Simone Basso (OONI)

2019-11-23

Over the last week, Iran experienced a nation-wide Internet blackout.

Most Iranians were barred from connecting to the global Internet and the

outside world, but they had access to Iran’s national Intranet: the

domestic network that hosts Iranian websites and services—all under the

government’s watch.

This major Internet blackout was rolled out on 16th November 2019, right

after protests erupted

across multiple cities in Iran. The protests (against economic

mismanagement and government corruption) were

sparked

by the government’s abrupt announcement to increase the price of fuel

(as much as

300%)

and to impose a strict rationing system. According to Amnesty

International, more than 100 protesters are believed to have been killed

over the last week, but this figure has been

disputed

by Iranian authorities. Amid the protests—which began on 15th November

2019 and are ongoing—access to the Internet was reportedly shutdown.

As of 21st November 2019, Internet access is gradually being restored.

In this report, we share data on the Internet blackout in Iran. We also

share technical observations for connecting to the Internet from Iran

during the blackout.

Nation-wide Internet blackout

Iran’s nation-wide Internet blackout is evident through several data

sources, all of which show that it started on 16th November 2019.

IODA data

The Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) project of the Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) measures

Internet blackouts worldwide in near real-time.

IODA data highlights three interesting aspects of Iran’s internet

blackout:

Cellular operators in Iran were disconnected first;

Almost all other providers in Iran followed suit over the next 5

hours;

Providers appear to have used diverse mechanisms to enforce

the blackout.

In order to track and confirm Internet disruptions with greater

confidence, IODA uses three complementary measurement and inference methods: Routing (BGP)

announcements, Active Probing, and Internet Background Radiation (IBR)

traffic. The routing announcements from BGP allow us to track

control-plane Internet reachability in an area, whereas Active Probing

and IBR shed light on different aspects of data-plane reachability.

These methods result in connectivity “liveness” signals, whose status

(for each country) is always publicly visible in the IODA dashboard.

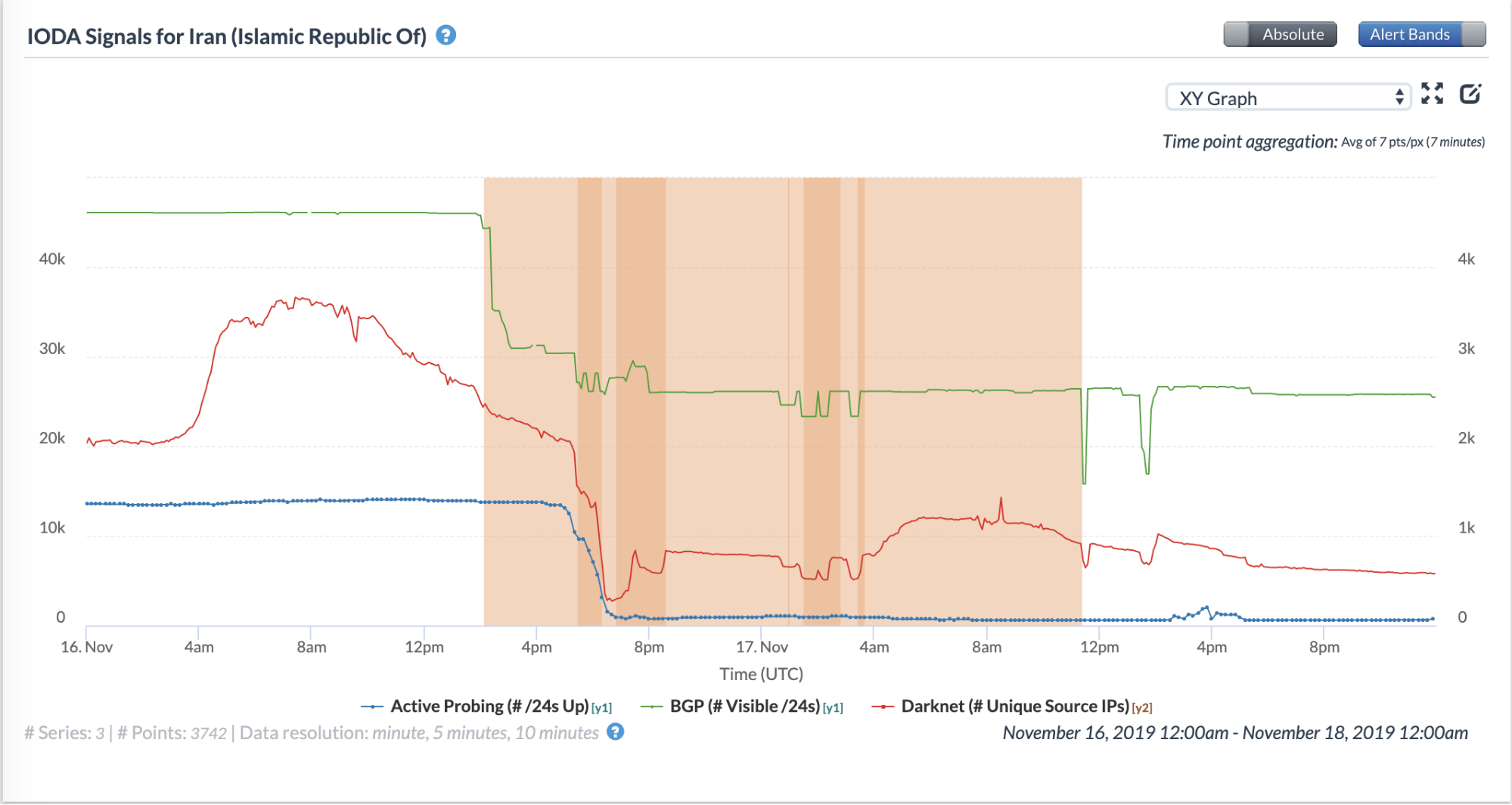

IODA data

clearly shows drops in signals from Iran on 16th November 2019, as

illustrated in the figure below.

Source: Internet Outage and Detection Analysis (IODA): Iran (Nov 16 to Nov 18)

Unlike other country-wide blackouts (such as those in

Syria

and

Iraq),

the signal drops did not all occur simultaneously and the magnitude of

the drops across the three different signals varied. For example, the

first drop occurred at around 14:00 UTC (17:30 local time in Iran), when

the BGP signal dropped by 33% (with the number of globally visible /24s

reducing by 15,000). However, the drops that the Active Probing and IBR

signals experienced at that time are almost negligible.

Then, from around 17:00 UTC on the same day, the Active Probing and IBR

time series dropped steadily until around 19:00 UTC. After 19:00 UTC on

16th November 2019, data-plane connectivity remained low until 09:00 UTC

on the morning of 21st November 2019, after which the Active Probing

time series began a slight trend upwards.

From the evening of 16th November 2019 to the morning of 21st November

2019, there was significantly reduced data-plane Internet connectivity,

although notably, some connectivity continued to persist even during

this time. Control-plane connectivity ostensibly remained at more than

50% of the pre-blackout connectivity throughout this time.

In the next section, we show that these differences in

signal-drop-patterns among the three IODA data sources are likely due to

both the adoption of diverse disconnection mechanisms and large

differences in the timing of their execution by various Iranian Internet

Service Providers (ISPs).

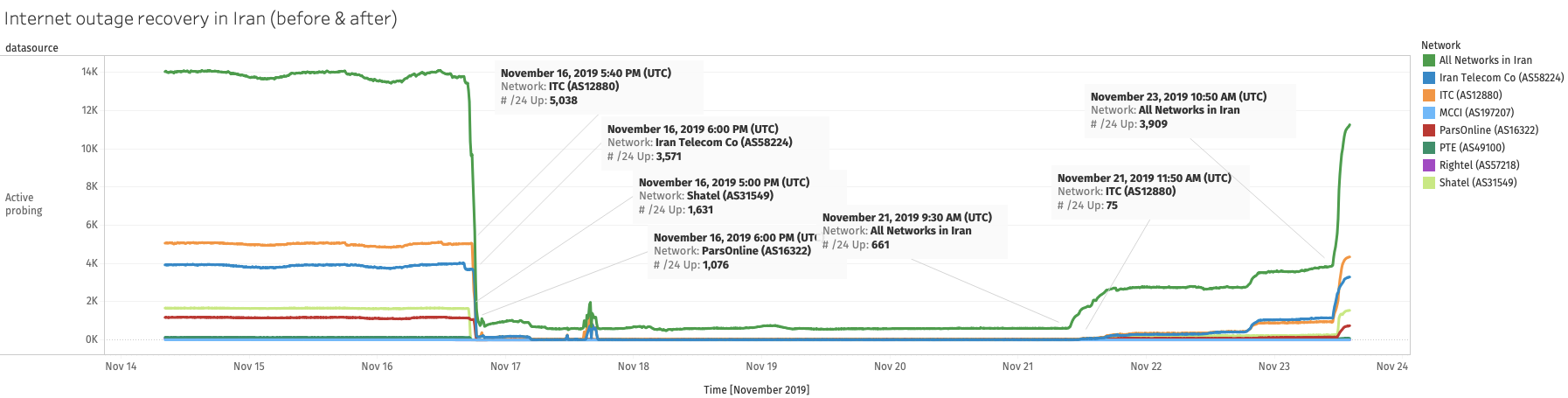

Network-level differences

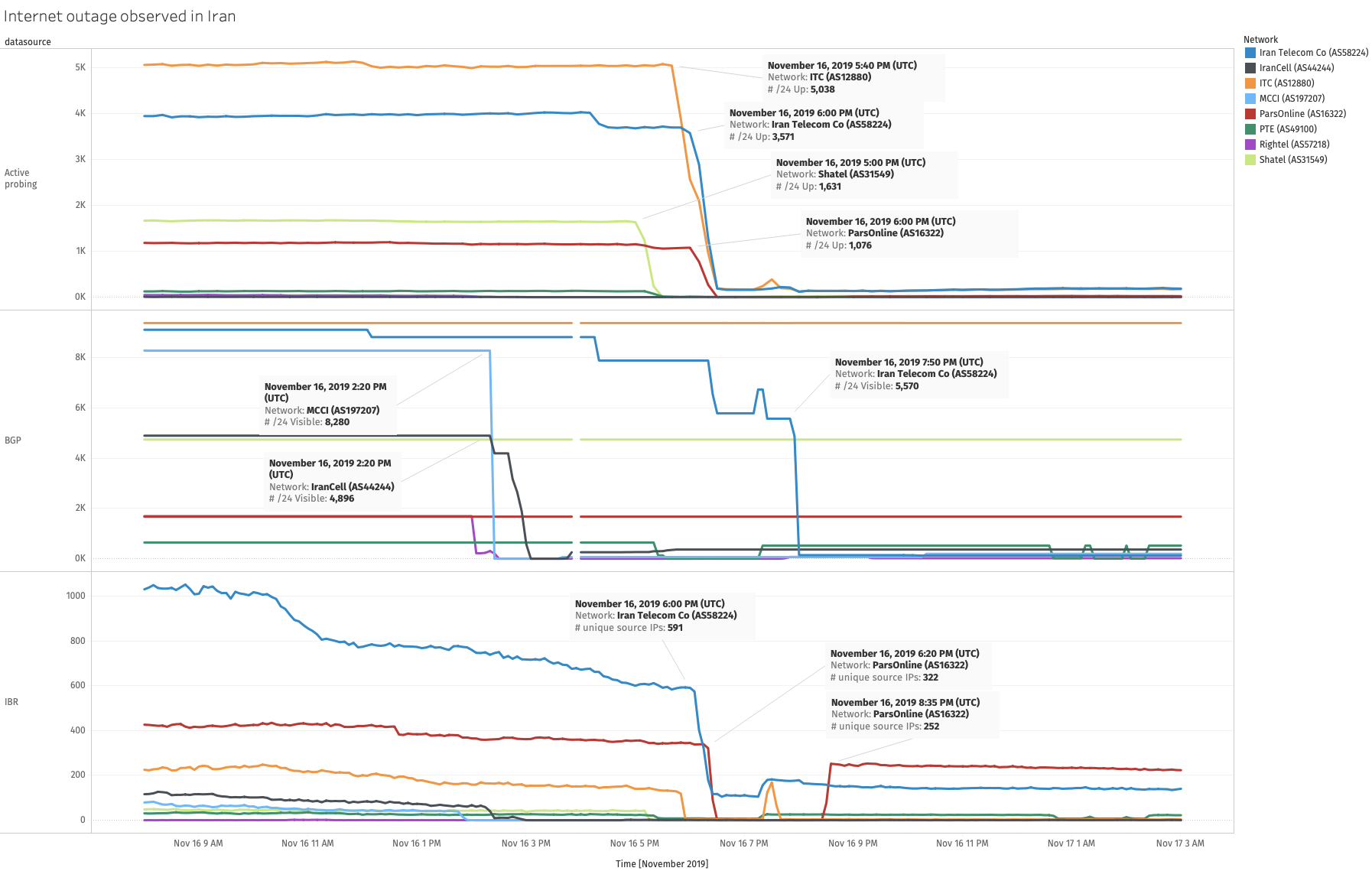

IODA data clearly shows drops in signals for various network operators

in Iran on 16th November 2019, as illustrated below (see legend on the

top-right of the chart to refer to each network operator).

Source: Internet Outage and Detection Analysis (IODA) data chart generated using a script

We observe significant differences in how different Autonomous Systems

(ASes) were affected by the shutdown.

First, there are timing differences—some networks lost Internet

connectivity a few hours before the others. For example, three large

cellular ISPs—MCCI (AS197207), IranCell (AS44244), and Rightel

(AS57218)—lost connectivity at around 14:00 UTC (17:30 local time in

Iran). These observations perhaps indicate that cellular operators in

Iran were instructed to shut down the Internet first (before fixed-line

operators were instructed).

Other ASes start losing connectivity later in the day at around 17:00

UTC (20:30 local time in Iran), but there are timing differences among

these ASes too. For example, the Active Probing and IBR signals for

Shatel (AS31549) drop sharply at around 17:00 UTC (20:30 local time in

Iran), but these signals for ParsOnline (AS16322) drop an hour later at

around 18:00 UTC (21:30 local time in Iran). These differences in timing

suggest that individual operators enforced the blackout independently

(as opposed to a single “kill-switch” that resulted in the simultaneous

disconnection of all operators).

Second, we observe dissimilarities in how the network-level blackouts

for different networks manifest in IODA’s signals. These dissimilarities

may reflect the use of different approaches by operators for

disconnecting their networks.

The three cellular ISPs’ blackouts are visible as drops in BGP

reachability at roughly the same time (~14:00 UTC); these drops are

accompanied by simultaneous drops in the IBR signal for these cellular

ASes as well. These results suggest that cellular operators perhaps

executed the blackout in their networks by blocking control-plane

reachability.

Other large Iranian ASes’ IODA signals exhibit differences compared to

the cellular ASes’ signals, and these differences are not limited to the

timings at which drops occur. For example, ITC (AS12880) has no drop in

the BGP signal on 16th November 2019, but the Active Probing and IBR

signals drop to nearly 0 at around 18:00 UTC (21:30 local time in Iran)

on that day.

On the other hand, Iran Telecom Co (AS58224) experiences not one, but

three different drops in the BGP signal (16:30, 18:30, 20:00 UTC),

only two of which are accompanied by drops in the other signals. The

Active Probing and IBR signals for ParsOnline (AS16322) drop to nearly 0

at 18:00 UTC on 16th November 2019, but surprisingly, at around 20:30

UTC on the same day, there is an increase in the IBR signal. These

results show that there can be disparities in the effects of the

blackout across networks.

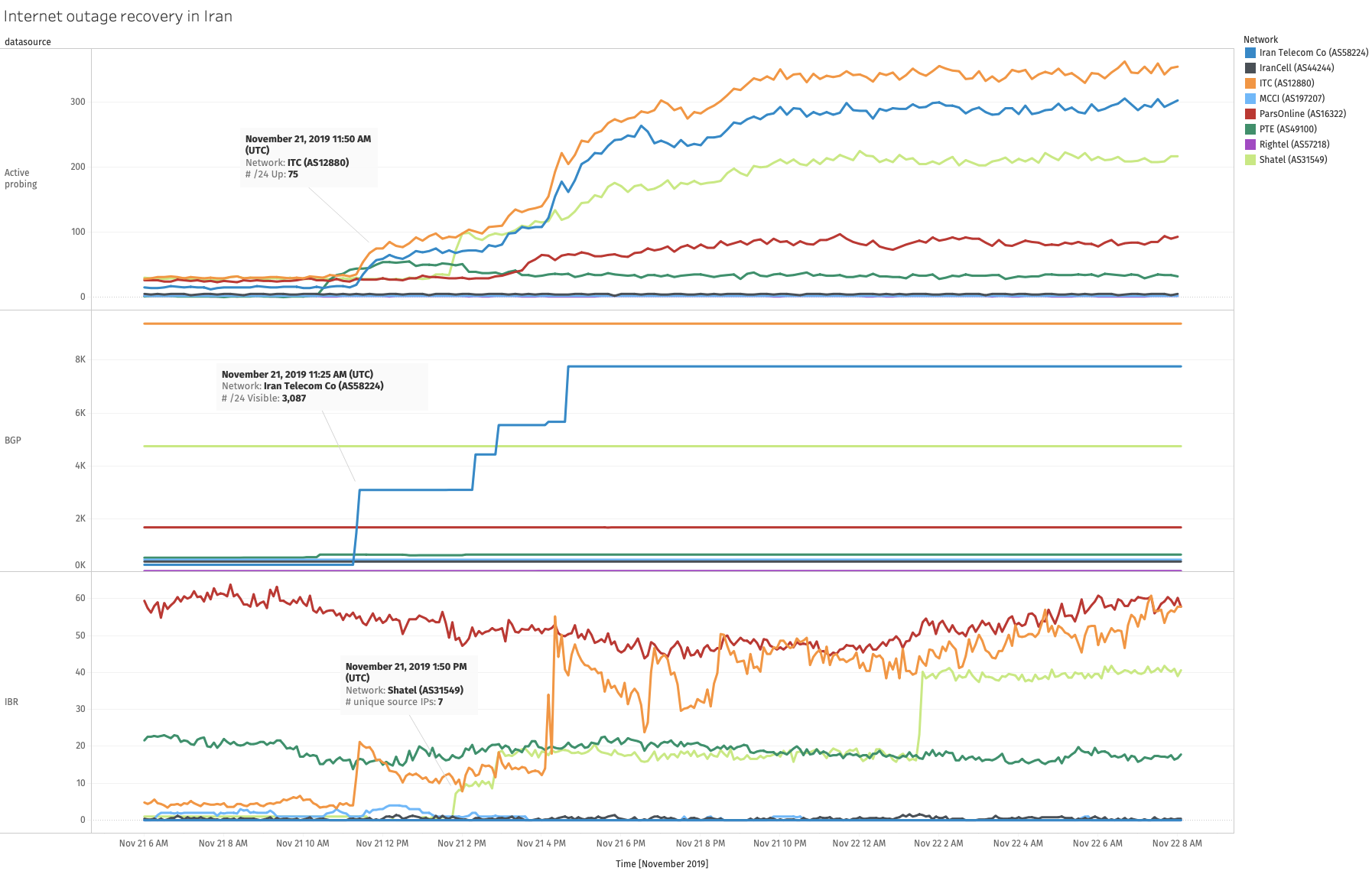

Signs of recovery

At around 10:00 UTC on 21st November 2019, we observe a spike in Active

Probing measurements.

Source: Internet Outage and Detection Analysis (IODA): Iran, Recovery of internet outage by network

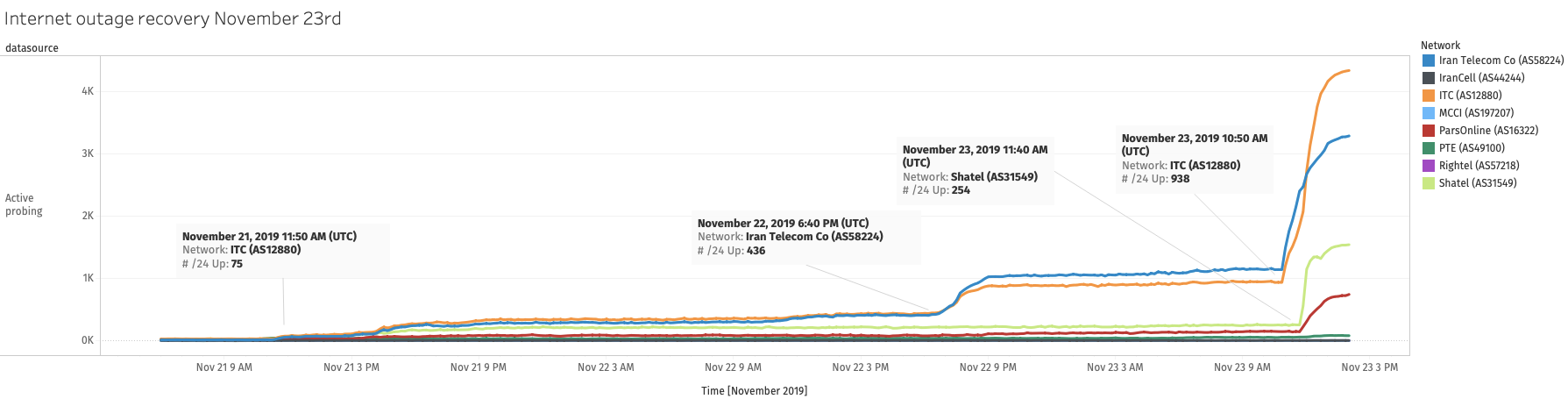

At around 10:50 UTC on 23rd November 2019, we can see another uptick in

the Active Probing IODA signal, showing that significantly more networks

were now reachable from the outside world.

Source: Internet Outage and Detection Analysis (IODA) data chart generated using a script

To put it into perspective, below is a chart that shows the IODA signals

for Active Probing before the outages and during the latest recovery

stage.

Source: Internet Outage and Detection Analysis (IODA) data chart generated using a script

This was also further confirmed with direct measurements from local

vantage points which showed that connectivity was being restored on many

more networks. We saw an increase in the amount of OONI measurements coming from Iran in

the morning of 23rd November 2019 (see sections below).

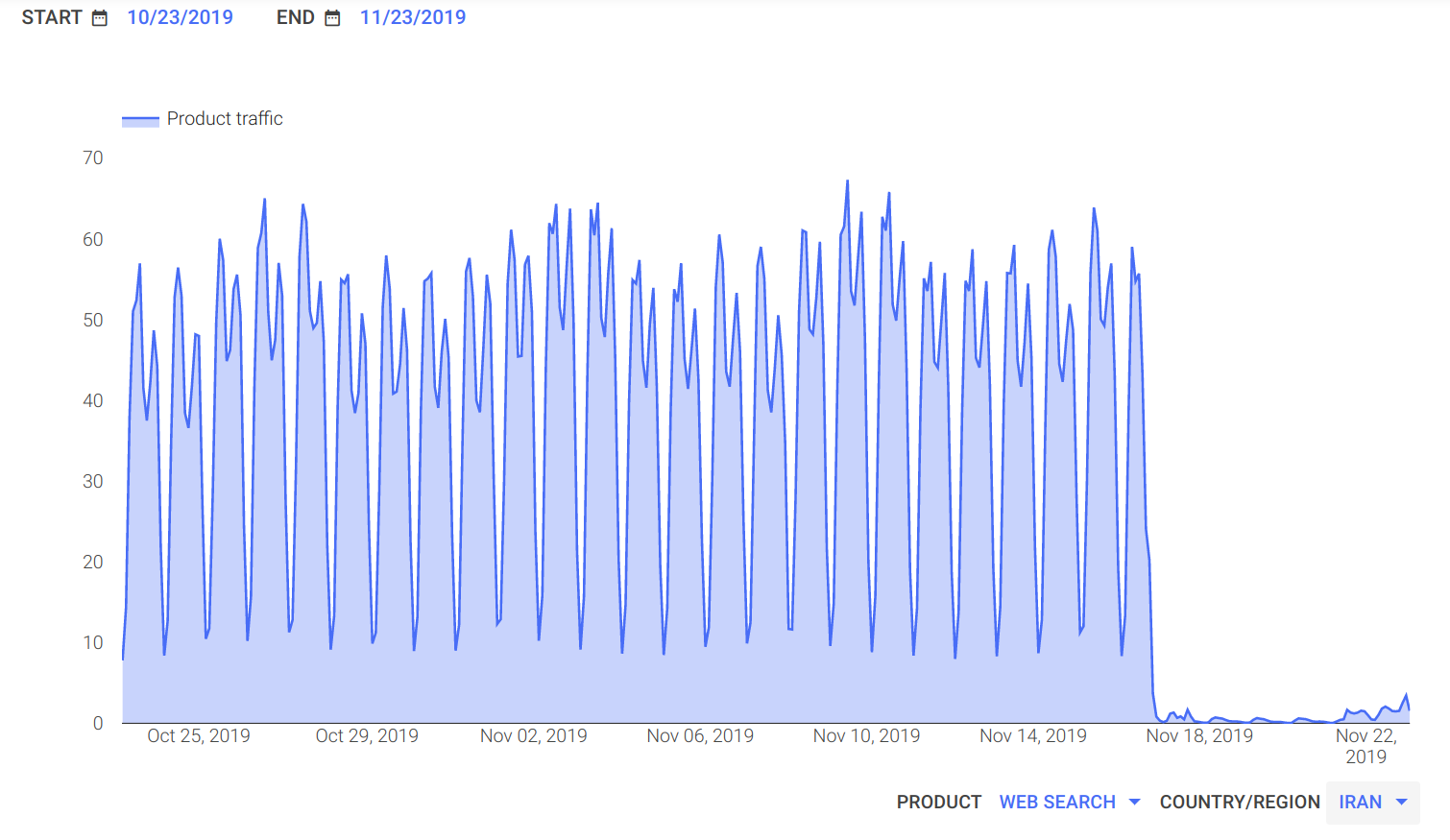

Other data sources

Iran’s Internet blackout is also confirmed by several other data

sources, such as Google traffic data,

Tor Metrics

(statistics on the use of Tor software,

which is used for online privacy, anonymity, and censorship

circumvention), and Oracle’s Internet Intelligence,

as well as by

NetBlocks

and

Cloudflare

reports.

Google traffic data,

illustrated below, shows an abrupt disruption of Google search traffic

originating from Iran at around 13:00 UTC on 16th November 2019.

Source: Google Transparency Reports: Traffic and disruptions to Google

As demonstrated by the above chart, the Internet blackout in Iran

appears to be ongoing since barely any Google search traffic has

originated from the country since 16th November 2019. Similarly to IODA

data, Google traffic data shows an uptick on 21st November 2019, with

more traffic gradually being restored from 22nd November 2019 onwards.

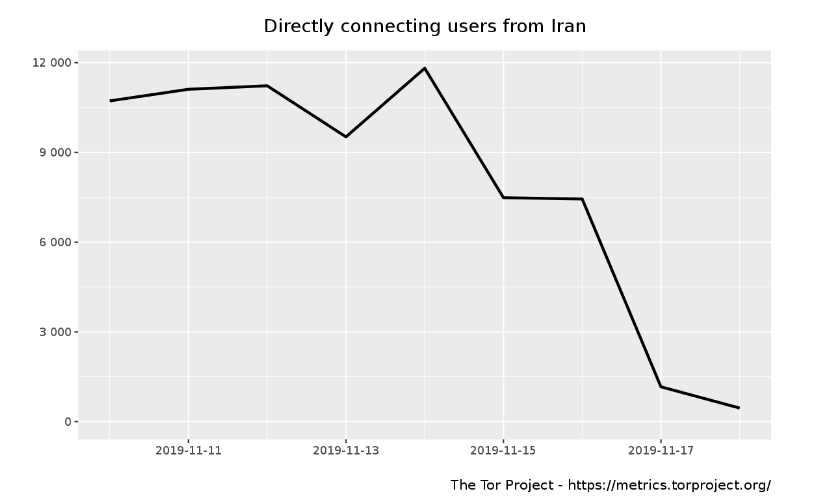

Tor Metrics below illustrate that the number of Tor users in Iran dropped abruptly on 16th November 2019.

Source: Tor Metrics: Directly connecting users from Iran

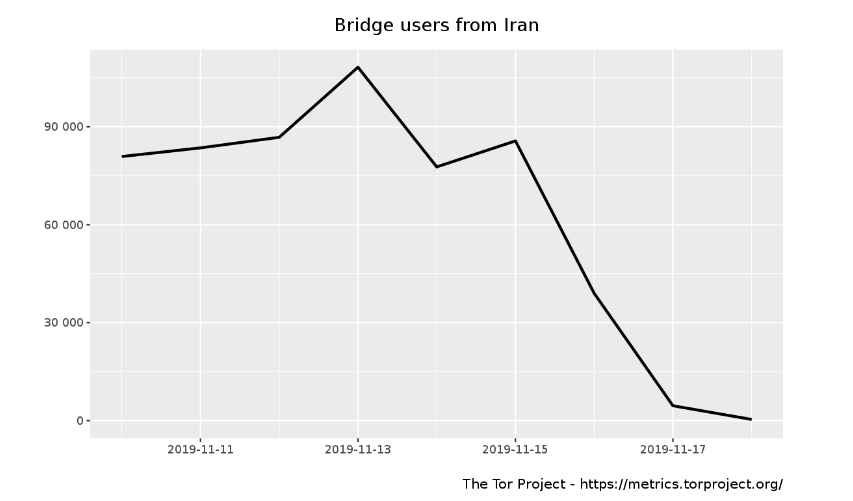

Similarly, we observe a sudden drop in the use of Tor bridges

(which are used to circumvent the blocking of the Tor network) in Iran on 16th November

2019 as well.

Source: Tor Metrics: Bridge users in Iran

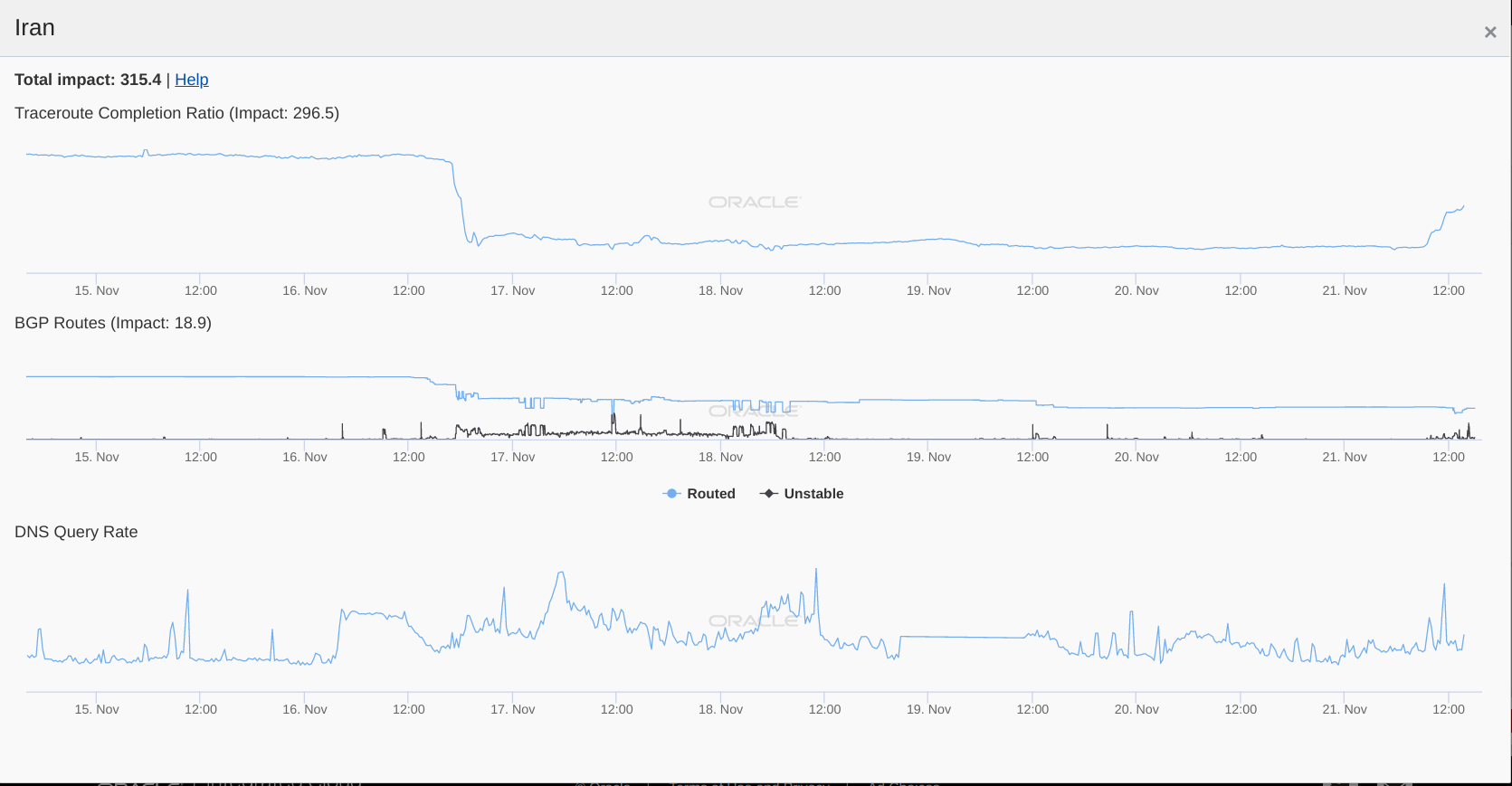

Oracle’s Internet Intelligence measures Internet

outages worldwide by tracking the drops in the routed BGP prefixes,

completed traceroutes, and DNS queries. These metrics suggest the

presence of an Internet disruption when they are significantly reduced

from baseline values of normalized counts of successful traceroutes,

volumes of DNS queries, and absolute counts of globally routed BGP

prefixes.

The following chart, taken from Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map,

suggests the presence of an Internet blackout in Iran (which they also

confirmed in their relevant publication

a few days ago) since there was a significant drop in completed

traceroutes and routed BGP prefixes.

Source: Oracle Internet Intelligence Map: Iran

It’s worth highlighting, however, that DNS requests increased recently,

showing that DNS traffic is able to reach the Internet.

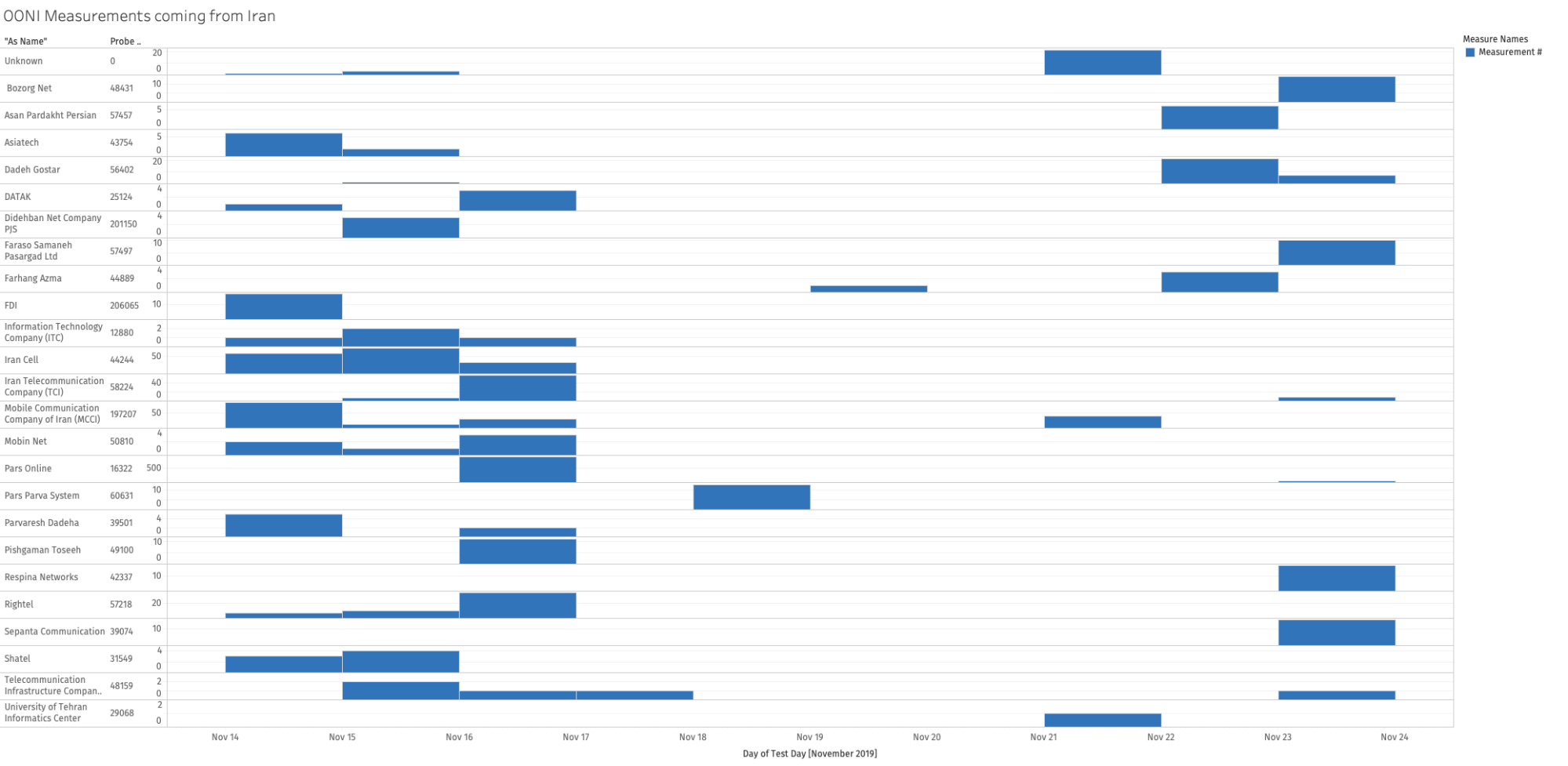

Throughout the course of Iran’s Internet blackout, we observe some

amount of traffic originating from some networks in Iran. The fact that

IODA traffic, for example, hasn’t dropped completely suggests that Iran

is not experiencing a total Internet blackout, as there are still some

connections to the Internet. This is also confirmed through OONI measurements

which were collected from Iran over the last week, despite the Internet

blackout.

The following chart shows the number of OONI measurements

collected from 49 different networks in Iran between 14th November 2019

to 23rd November 2019.

Source: OONI measurements: Iran (from OONI’s fast-path pipeline)

As OONI Probe requires Internet

connectivity in order to perform tests (and submit test results for

publication), the collected OONI measurements from Iran

over the last week demonstrate that the Internet blackout was not

total, since some people were still able to connect to the Internet on

some networks.

Throughout the Internet blackout (from 16th November 2019 to 23rd

November 2019), OONI Probe was run on the following networks:

AS12880 (DCI-AS - Information Technology Company (ITC))

AS16322 (PARSONLINE - Pars Online PJS)

AS197207 (MCCI-AS - Mobile Communication Company of Iran PLC)

AS25124 (DATAK - DATAK Internet Engineering Inc)

AS29068 (UT-AS - University of Tehran Informatics Center)

AS39074 (IR-SEPANTA-ISP - Sepanta Communication Development Co. Ltd)

AS39501 (NGSAS - Parvaresh Dadeha Co. Private Joint Stock)

AS42337 (RESPINA-AS - Respina Networks & Beyond PJSC)

AS43754 (ASIATECH - Asiatech Data Transmission company)

AS44244 (IRANCELL-AS - Iran Cell Service and Communication Company)

AS44889 (AZMA-AS - Farhang Azma Communications Company LTD)

AS48159 (TIC-AS - Telecommunication Infrastructure Company)

AS48431 (MAXNET-AS - Bozorg Net-e Aria)

AS49100 (IR-THR-PTE - Pishgaman Toseeh Ertebatat Company (Private Joint Stock))

AS50810 (MOBINNET-AS - Mobin Net Communication Company (Private Joint Stock))

AS56402 (DADEHGOSTAR-AS - Dadeh Gostar Asr Novin P.J.S. Co.)

AS57218 (RIGHTEL - “Rightel Communication Service Company PJS”)

AS57457 (ASAN-AS - Asan Pardakht Persian Private Stock)

AS57497 (FARASOSAMANEHPASARGAD - Faraso Samaneh Pasargad Ltd.)

AS58224 (TCI - Iran Telecommunication Company PJS)

AS60631 (PARVASYSTEM - Pars Parva System Co. Ltd.)

Not everyone in Iran was disconnected from the Internet during the

blackout. We were told that some hosting providers, banks, businesses,

and journalists were able to maintain access to the Internet. Meanwhile,

most people in Iran were limited to using Iran’s national Intranet

during the Internet blackout.

Technical observations from manual testing

To better understand how the Internet blackout was technically

implemented in Iran, we ran a series of tests locally.

We performed a TCP traceroute to port 443 on a host located in Europe

(mtr -n -T 37.218.xx.xx -P 443 –report) from a vantage point inside of

Iran, connected to the MCCI network (5.210.xx.xx).

By observing the network traffic data from both sides, we can see that a

RST packet is injected at both ends of the connection.

Packet trace from host in Europe:

5274 122.556004 5.210.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 54 58823 → 443 [RST, ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=0 Len=0

5359 123.806532 5.210.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 54 46267 → 443 [RST, ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=0 Len=0

5406 124.600632 5.210.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 54 40903 → 443 [RST, ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=0 Len=0

Packet trace from host on MCCI (Iran):

53 10.987705 192.168.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 74 55849 → 443 [SYN] Seq=0 Win=29200 Len=0 MSS=1460 SACK_PERM=1 TSval=216567 TSecr=0 WS=128

71 12.013533 192.168.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 74 [TCP Retransmission] 55849 → 443 [SYN] Seq=0 Win=29200 Len=0 MSS=1460 SACK_PERM=1 TSval=216824 TSecr=0 WS=128

131 14.029151 192.168.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 74 [TCP Retransmission] 55849 → 443 [SYN] Seq=0 Win=29200 Len=0 MSS=1460 SACK_PERM=1 TSval=217328 TSecr=0 WS=128

301 18.190035 192.168.x.x → 37.218.x.x TCP 74 [TCP Retransmission] 55849 → 443 [SYN] Seq=0 Win=29200 Len=0 MSS=1460 SACK_PERM=1 TSval=218368 TSecr=0 WS=128

469 23.198129 37.218.x.x → 192.168.x.x TCP 60 443 → 55849 [RST, ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=0 Len=0

It is interesting to observe that it takes many seconds to receive the

RST packet on the MCCI network, making it plausible that the network is

buffering packets for a large amount of time.

Further research and investigation into this pattern and behaviour is

left for future work.

Iran’s Intranet

Back in 2011, a senior Iranian official

announced

government plans to launch a national Intranet, the “National Information Network (NIN)”,

which would host Iranian websites and services, and promote Islamic

values.

Research on Iran’s network infrastructure,

published in 2012, revealed the

presence of a “hidden Internet”, with private IP addresses allocated on

the country’s national network. Telecommunications entities were found

to allow private addresses to route domestically (whether intentionally

or unintentionally), creating a hidden network only reachable within

Iran. This research also found that records, such as DNS queries,

suggest that servers are assigned both domestic IP addresses and global

ones.

While it was initially

reported

that Iran’s Intranet (called

“SHOMA”

in Persian) would be launched in 2012, it was rolled out in August 2016.

Many Iranian Internet users, however, have reportedly stated

that they either were not aware of Iran’s Intranet, or that they didn’t

take it seriously. The main

arguments

that the Iranian government has highlighted to get Iranians to use the

Intranet and host their websites there is that it is supposedly faster

and more secure. As part of our recent discussions with Iranian Internet

users, they have claimed that Iran’s Intranet cannot work properly

without the Internet, and that every day electronic devices become more

vulnerable as a result of not receiving updates.

But amid Iran’s nation-wide Internet blackout, for most Iranians it has

only been possible to access websites and services hosted on Iran’s

Intranet.

Connecting to the Internet from Iran

Through manual testing, we were able to determine that it could

theoretically be possible to use DNS tunneling to get traffic to

leave Iran.

Below we share the DNS query from the MCCI mobile network to

whoami.akamai.net, showing the address of the resolver.

# dig whoami.akamai.net

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;whoami.akamai.net. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

whoami.akamai.net. 94 IN A 185.5.159.155

;; Query time: 76 msec

;; WHEN: Wed Nov 20 09:50:08 EST 2019

When performing an A lookup for a random subdomain (therefore bypassing

any potential local DNS cache), we can see that the query succeeds.

# dig dvcdjtje7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;dvcdjtje7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

dvcdjtje7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io. 300 IN A 1.2.3.4

;; Query time: 305 msec

;; WHEN: Wed Nov 20 09:17:06 EST 2019

We repeated similar experiments on the resolvers of a fixed line ADSL

network.

# dig dassdnjasde7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io @217.218.155.155

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;dassdnjasde7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

dassdnjasde7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io. 300 IN A 1.2.3.4

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

xip.io. 86400 IN NS ns-1.xip.io.

xip.io. 86400 IN NS ns-2.xip.io.

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION:

ns-1.xip.io. 86400 IN A 166.78.161.251

ns-2.xip.io. 86400 IN A 192.237.180.202

;; SERVER: 217.218.155.155#53(217.218.155.155)

;; WHEN: Wed Nov 20 10:34:01 EST 2019

As we can see, requests to the secondary DNS resolver 217.218.155.155

are let through.

This means that it’s possible to get the upstream recursive resolvers of

the ISP to perform DNS queries on our behalf. This channel could

theoretically be used to transfer some data to the Internet at a very

low throughput and with high overhead. Tools like

iodine could be used.

When querying the primary DNS resolver 5.200.200.200, the result is a

SERVFAIL.

# dig dassdnjasde7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io @5.200.200.200

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: SERVFAIL, id: 37763

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;dassdnjasde7z.1.2.3.4.xip.io. IN A

;; Query time: 142 msec

;; SERVER: 5.200.200.200#53(5.200.200.200)

;; WHEN: Wed Nov 20 10:33:40 EST 2019

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 57

It is, however, interesting to note that queries for records which are

likely cached, work as expected.

# dig yahoo.com @5.200.200.200

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 51852

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 6, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;yahoo.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 98.137.246.7

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 72.30.35.9

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 98.138.219.232

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 98.137.246.8

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 98.138.219.231

yahoo.com. 1087 IN A 72.30.35.10

;; Query time: 52 msec

;; SERVER: 5.200.200.200#53(5.200.200.200)

;; WHEN: Wed Nov 20 10:52:51 EST 2019

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 134

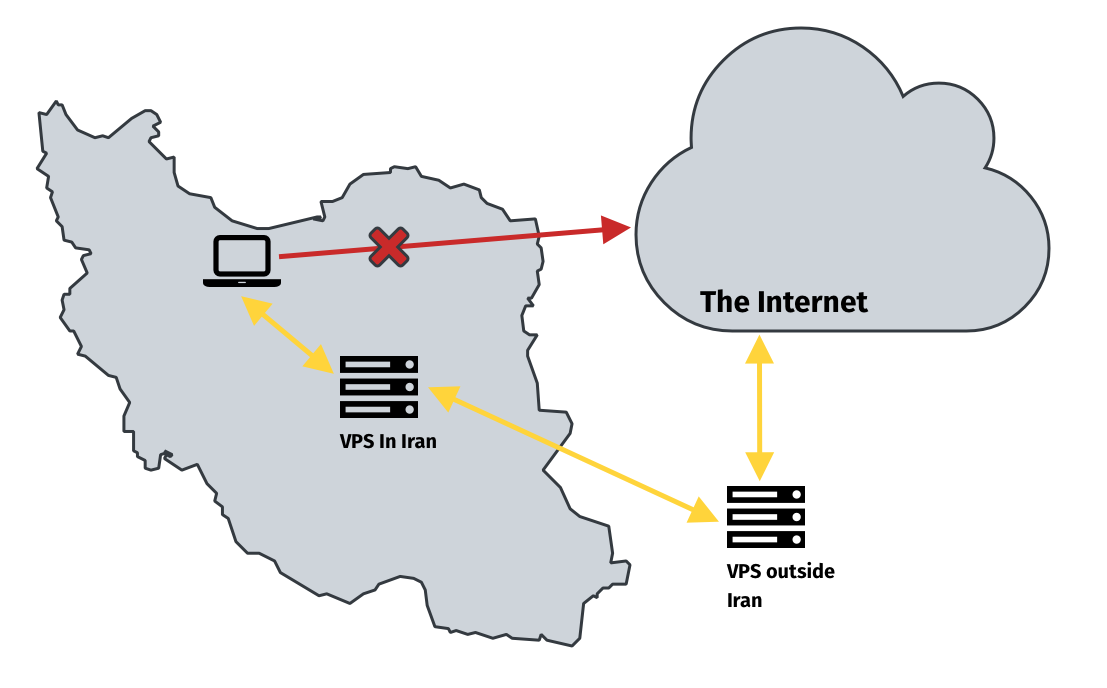

It is possible for Iranian citizens to acquire virtual private servers

(VPS) inside the country. Through local testing, we were able to

determine that these VPS hosts have connectivity with both users inside

the country, but also to the Internet. This makes it possible to use

these servers to setup a local proxy inside of the country and to use

that proxy to tunnel traffic to another proxy outside Iran. Information

about this method has also been circulated in Iranian Telegram forums.

However, locals using VPS in Iran to connect to the global Internet

reported that they may have experienced throttling. We do not have

measurement data available to confirm this, but it could be an area for

further research. If VPS traffic is in fact being throttled, it would

not be the first time that Iran has throttled Internet traffic.

Conclusion

As protests

erupted in Iran, the Internet was shut down on a nation-wide level over the

last week.

Iran’s nation-wide Internet blackout is confirmed by several data

sources, such as

IODA,

Google traffic data,

and Oracle’s Internet Intelligence data.

These data sources show that the Internet blackout in Iran started on

16th November 2019 and has been ongoing. As of 21st November 2019 (and

more drastically from 23rd November 2019), Internet connectivity is

being restored in Iran.

IODA data,

which provides publicly-accessible network-level granularity, shows that

Iranian cellular operators were disconnected first on 16th November 2019

(followed by almost all other operators over the next 5 hours), and that

ISPs appear to have used diverse mechanisms to enforce the blackout. In

an orthogonal study, by analyzing packet captures from the MCCI

(AS197207) network, we found that a RST packet is injected at both ends

of the connection.

During the blackout, most Iranians were barred from connecting to the

global Internet, but they still had access to Iran’s national intranet:

the domestic network hosting Iranian websites and services. Yet, OONI measurements

(which require Internet connectivity) were collected from multiple

networks in Iran between 16th November 2019 to 23rd November 2019,

showing that the internet blackout was not total.

To explore whether and how connectivity to the Internet could be

possible from Iran during the blackout, we performed manual testing

locally. We found that DNS tunneling could possible be a low

bandwidth solution to get network traffic to leave Iran. We also found

that it was possible to connect to the Internet by using virtual

private servers (VPS) to setup a local proxy in Iran and use that

proxy to tunnel traffic to another proxy outside Iran.